The Walnut Tree

Mrs. Gina Loehr

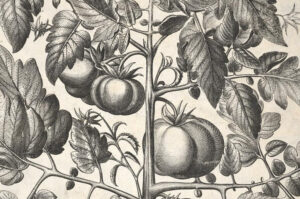

In the front yard of the farmhouse where my father-in-law, Norman, lived his entire life, there stood a walnut tree. Every fall, the arboreal giant threw down a veritable hailstorm of green orbs that littered the lawn, creating a minefield ready to upend the unwary walker. When I look out over that yard, or when my children and I pass through it on our way down for a visit, I think about that tree and about a good man in the sunset of his life.

By the time I joined the family, Norm was getting on in years. I don’t know how it all worked in earlier decades, but by then he had conceived of an annual ritual to handle the onslaught of inaccessible walnuts. He would send his grandchildren out front with five-gallon buckets to collect the golf-ball-sized fruits, and then store the loaded tubs — usually six or eight of them — in the basement for the year.

By the time I joined the family, Norm was getting on in years. I don’t know how it all worked in earlier decades, but by then he had conceived of an annual ritual to handle the onslaught of inaccessible walnuts. He would send his grandchildren out front with five-gallon buckets to collect the golf-ball-sized fruits, and then store the loaded tubs — usually six or eight of them — in the basement for the year.

Load by load, the harvest would make its way to the kitchen, and Norm would slowly work his way through the pails, one of which always rested next to his chair at the kitchen table. Sitting there, metal A-frame nutcracker couched in his giant farmer’s palm, Norm would greet relatives and friends as they came and went, discussing the weather, the harvest, the latest turkey sighting, or sharing stories about bygone days, all while his hands peeled and cracked the endless supply of walnuts.

The process wasn’t always efficient. A single meat might take half an hour to be released from its shell if it was a hard nut to crack, or if company was especially engaging that afternoon. Sometimes, a grandson home from college or a daughter-in-law up from next door would grab the second nutcracker that sat ready and waiting on the table and lend a hand. Such unrequested assistance always lit up Norm’s face; words of gratitude were not required.

A single meat might take half an hour to be released from its shell if it was a hard nut to crack, or if company was especially engaging that afternoon.

Eventually, each five-gallon load of green balls would be stripped and cracked, its treasure extracted, and a gallon pail would be filled up with edible bits and pieces. My mother-in-law stored them in the fruit cellar, from which, eventually, they might find their way into breads or pies or salads, or be chopped atop ice cream.

But the point wasn’t actually the walnuts. The point was the work. As he grew older, Norm’s dream was not to stop working. His dream was to work until the day he died.

For the vast majority of his life, Norm woke early every morning and took up the day’s labors. In this he was no different than his fathers before him, who brought forth food by the sweat of their brows. And in this he was also paving the way for his five sons. From their earliest days — alongside their six sisters, though in their own masculine way — they were formed by his example. And when they were old enough they rose with their father, and joined him in his labor, learning to do the work that a good man does.

Norm woke early every morning and took up the day’s labors. In this he was no different than his fathers before him, who brought forth food by the sweat of their brows.

His sons learned from him not just the particulars – how to drive a tractor, or farrow a pig, or a hundred other chores. They learned to labor for the welfare of their loved ones, to tend to the gifts that had been entrusted to them, and to measure their days not in the (endless) amount of work before them, but in the accomplishment of work well done.

Over time, three of his sons took on more primary operations of the farm, and Norm took on less. If he was saddened by this, he did not show it; he looked on with pride as the change gradually occurred. In the natural course of things, his sons increased and he began to decrease. But even in his later years, Norm never did embrace the notion of retirement. Work was borne deep in his body. In the days when he could labor at farm chores, he did. And when eventually he couldn’t, he continued his work, even after his field was the mere size of the kitchen table. And on those days, still the center of his family, he harvested walnuts.

Over time, three of his sons took on more primary operations of the farm, and Norm took on less. If he was saddened by this, he did not show it; he looked on with pride as the change gradually occurred. In the natural course of things, his sons increased and he began to decrease. But even in his later years, Norm never did embrace the notion of retirement. Work was borne deep in his body. In the days when he could labor at farm chores, he did. And when eventually he couldn’t, he continued his work, even after his field was the mere size of the kitchen table. And on those days, still the center of his family, he harvested walnuts.

The tree is gone now, and so is Norm. But it’s a beautiful consolation that even with his labor finished, the blessings of his work carry on, as my sons in turn learn from his son the work that a good man does.