Advent & the Prognosticators

Mr. Matthew Giambrone

“Until the day when God will deign to reveal the future to man, all human wisdom is contained in these two words,—‘Wait and hope.’”

Alexandre Dumas

Will there be another pandemic? Or is such talk just fear-mongering? Will there be peace in the Middle East or chaos? Will overseas wars be contained or explode into World War III? Will America solidify her status as the breadbasket of the world? Or will we face mass hunger? Will Artificial Intelligence create millions of new jobs — or will it lead to ninety-nine percent unemployment?

Will all of the above collectively unleash a dystopian nightmare? Or will we usher in a utopian, leisure-based paradise, in which the people of Earth spend their gentle days pondering art and philosophy while being served cocktails by robots?

The answer to all of these questions is yes. According to the experts.

A friend wrote to inquire whether I think our national supplies of food and other critical resources will hold up and flourish, or whether we’ll face empty store shelves again some day, as we did during that strange era called Covid. My bold and confident answer: “I don’t know.” I’m prone to offer the same response to most other such forward-looking questions, as well. I don’t know. Maybe it’s one or maybe the other; maybe it’s something else we haven’t thought to ask. I’m not much of an expert. And I’m not much good at prognosticating.

But as we exit each successive year and face the understandable temptation to try to peer over the horizon into the next, such questions, and various attempted answers, inevitably abound. Presumably “I don’t know” was not the answer my friend was looking for. “There is ample food in the country; our distribution infrastructure is the best in the world; there’s nothing to worry about.” That’s something he could take some comfort in. Or, “The supply chain is facing a downward spiral that the government doesn’t want you to know about; given wars and agro-terrorism on top of that, we’ll see the system collapse within three years, leading to regional starvation.” Well, less comforting, but at least he wouldn’t need to remain in suspense. But “I don’t know”?

It is, counterintuitively, the answer that is most helpful. Or at least most hopeful.

We always want to know what’s going to happen. And when we want something, we can generally find someone willing to sell it to us. The armies of expert prognosticators populating news shows and podcasts will confidently predict anything that you care to have confidently predicted. They make a living at it. We fund that living by spending dollars or watching ads. These professionals speak with certainty about upcoming death tolls, gold prices, inflation rates, sports scores, supply chain recovery or collapse, and nuclear holocaust. And they get particularly active around the end of the year. It seems to be one of our steadiest New Year’s traditions. (Curiously, I don’t recall any of them in the final hours of 2019 having mentioned the fact that within three months the world would shut down.)

Consider a short mental experiment. Suppose we decide to shift gears for Hearth & Field. Today we’ll send everyone on our mailing list a prediction about whether a particular stock will go up or down tomorrow. To half of the list we predict up; to the other half we predict down. If you were on the “up” half, and if it goes up, then the following week we’ll send you another prediction; the “down” half of the list won’t hear from us again. The second go-round will follow the same pattern — half the list gets one prediction, and half gets the opposite, and we subsequently abandon the half that got the wrong one. We keep doing this for a while; no more reflections on gardens or poultry or supply chains, just a steady stream of stock picks. Over time, our list keeps shrinking by half, but after let’s say ten weeks, a small number of folks remain, and they have received ten perfect predictions in a row. Suppose you’re one of them — Hearth & Field must seem brilliant. And valuable. It is right about then that we stop offering these predicti0ns for free and make the eleventh available for a sizable fee.

As business models go, it is not the most scrupulous, but it makes a point. Even absent an intentional con game, this hypothetical algorithm (articulated by the mathematician John Allen Paulos) illustrates how any prognosticator can look good if he makes lots of predictions and people don’t notice the wrong ones. You’ll find the news segments always introduce their savvy guest as having predicted thus and such half-dozen things correctly, but they don’t seem to remember to list the failures.

Given a whole industry of prognosticators on a twenty-four-seven news cycle, endlessly predicting contradictory things, some folks will necessarily end up being right for long stretches. If you flip enough coins enough times, one of them will come up heads a goodly number of times in a row. The same coin, on its next flip, has an exactly fifty percent chance of coming up heads. Which is approximately as helpful as our best prognosticator.

And despite it all, as I said, when they tried at the end of 2019 to peer over the horizon into subsequent decade, not one of them happened to mention that the entire globe was about to lock itself down for months on end. Modernity tends to see things in binary that aren’t binary (and vice versa) and assembles its prediction games accordingly. But Covid broke the binary. It was like the coin landing on its edge, or maybe like the coin exploding on impact. In that way, Covid was a great reminder (which we are already at acute risk of forgetting): the truly unexpected events tend to be the ones that shape history. And you cannot foretell them just by playing both sides of the expectable.

The long and the short is that we have very little clue about the future. A handful of general things we do know with confidence: God will not abandon us. Men will continue to be fallen creatures. (The writings of Augustine of Hippo will prove far more insightful as to how A.I. is likely be used than will the corporate projections of Silicon Valley.) But on the whole, we know precious little of the details.

It is not helpful to pretend otherwise. False confidence is more dangerous than honest ignorance. False confidence can lead us to be very particularly prepared for a very particular future and very ill prepared for an infinitude of others. More importantly, God does not seem to want us fixated on the future. He prefers us trustingly, confidently present in the present. And that is the whole framework for this thing, this virtue, called hope. If we could conjure the future there would be no place in the present for such a virtue.

Hope does not, of course, preclude taking measures to be ready for what may come; rather the opposite: hope holds that something will come that is worth being ready for. Should some of us choose to have nothing but the sandals on our feet because we are trusting entirely in Providence, that is probably a very good thing. But if we chose to have nothing but the sandals on our feet because we are trusting entirely on a web retailer to replace them with a new pair of Nikes, or if we have nothing in the pantry because we are trusting entirely on just-in-time provisions from an iffy supply chain, that is another matter.

That sort of behavior does not suggest we live in the present with our hope in the Lord; it suggests that we live in a pre-supposed future — a future of steady supply chains and global peace and slave-market sneakers — and that our hope is in the Amazon delivery truck. It is better to admit ignorance and to be ready in reasonable ways, particularly the reasonable ways in which our grandparents used to be ready, back before people thought they didn’t need to be. In rich times and in poor times, in war and in peace, with or without a functioning supply chain, it is always a smart and happy and securing thing to have food in the pantry and seeds for the spring. Certain behaviors and systems and lines of defense tend to survive regardless of what the future holds; some even tend to benefit from the volatility and uncertainty. Now is surely as good a time as there’s ever been to think about and tend to such things. Hope does not preclude this.

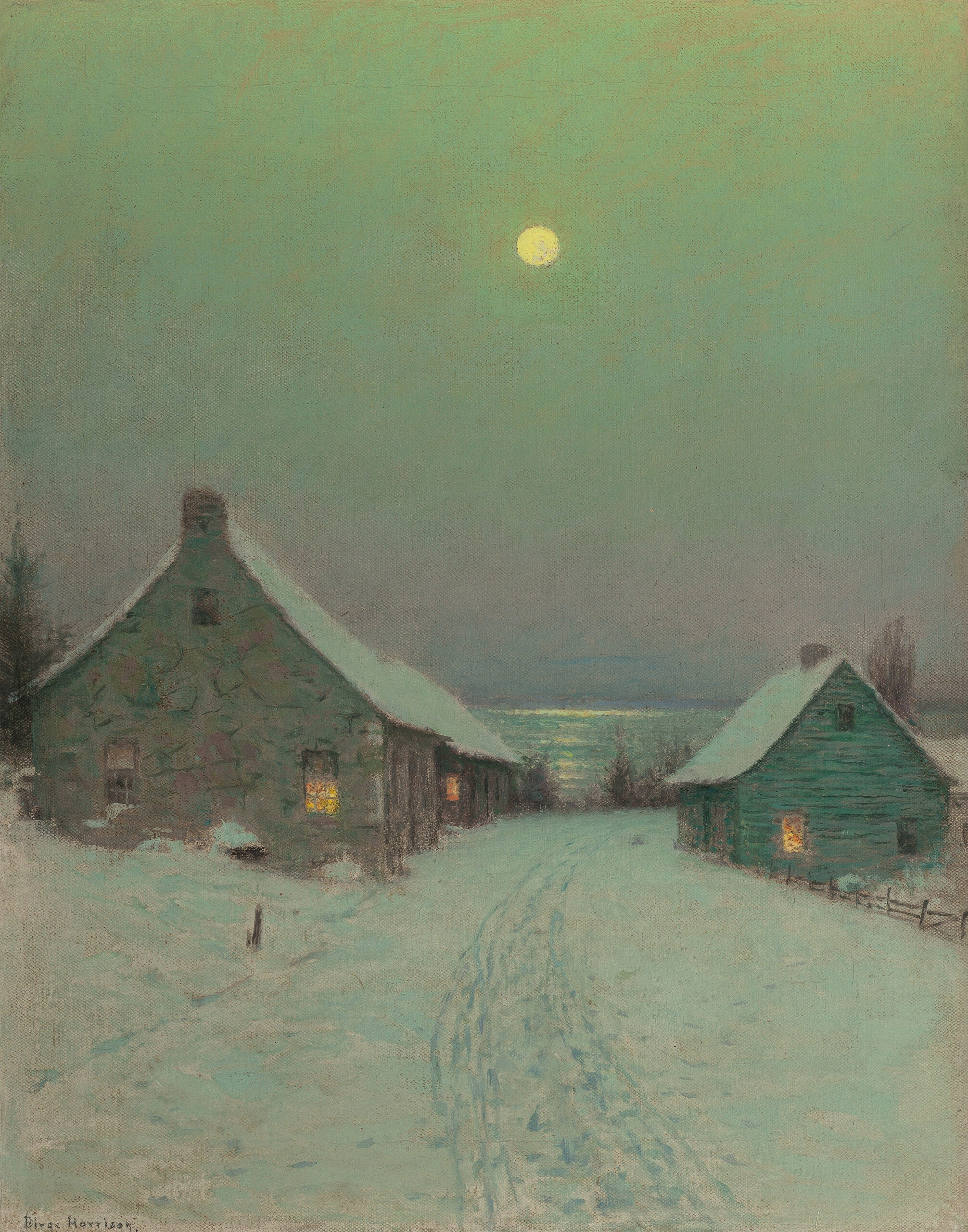

But hope does preclude obsessing about it. Hope precludes worrying about it. Hope precludes a dysfunctional preoccupation with it, a sick habit of constantly mentally transplanting ourselves into a time that does not yet exist. The future is and should be a mysterious land — a land forbidden to us. We can only venture there as trespassers, and then only in the dark.

Our desire to steal into that darkness, our yearning to peek, is usually born not of hope for what lies there but of fear. We are anxious about many things, and afraid of the worst of them. This is understandable! But it is also understandable that my smallest children are likewise afraid of the dark, afraid of what lies there, afraid of countless small dangers, real or imagined. Yet it is with utmost honesty that I look into their wide and tearing eyes and say don’t be afraid. Everything is okay. I’ll protect you.

For I know what they do not. If I shield them from all minor harm, I’ll be doing no favors. And most of their fears are imagined. And any dangers in a dark room at the end of the hallway that are not imagined will not actually hurt them greatly, at least not in the grand scope of their lives, much less their eternity. The dangers seem big to them because they themselves are small. But in the end, my children will grow and all evils will contract until the evils are as nothing in hindsight. It is the same when, with perfect foresight, with greatest tenderness, our Lord looks at us, his children, and says be not afraid.

So as the final days of the year go by, turn off the noise and the news and the new year predictions. Read old books and talk to old friends. Light up the candles and power down the screens. Let the hours pass peacefully, quietly, set within the days that actually contain them. For we can be completely certain of just one thing: they lead on to a birth that bestows hope upon the universe. It is the birth of the only one who is really worth hoping for or hoping in: God become man. It is the truly unexpected event shaping all of history; but now, with sure confidence, we can expect it. And that is what Advent is about. Advent reveals to us everything that we really ought to know and feel and proclaim about our future. Beyond that, none of us are very good prognosticators.