Brewing Beer,

Building Culture

Dr. R. Jared Staudt

With modern culture slipping into ever deeper decline, anyone would be justified by a feeling of discouragement at the prospects of renewal. Although it is difficult, though not impossible, to change large scale institutions and practices, culture can be formed in compelling ways in the home and in local communities. That is not a cop-out, but a recognition that culture arises precisely from shared convictions and practices, necessitating that we become creators of culture through our work and family life. Thinking of culture in this way places more prominence on our choices that involve many smaller opportunities, ones that are more within our sphere of influence. In fact, focusing on culture as our own daily way of life places more prominence on seemingly insignificant details.

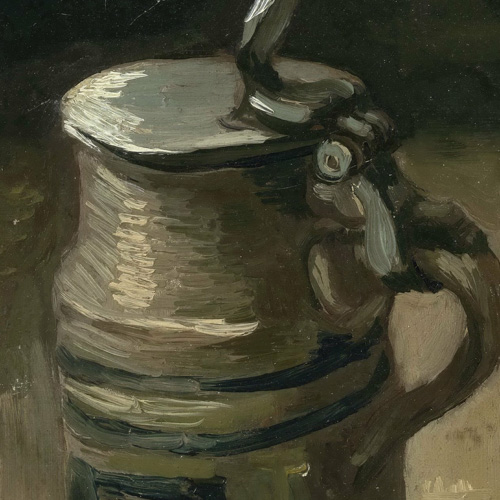

Long before the rise of the mass state and the Industrial Revolution, beer provided one example of the importance of food and drink in shaping a community’s culture. It was one of the most ordinary of cultural products that could be made by the average person in the home, prior to the advent of large breweries and international brewing conglomerates. The origin of brewing, in fact, takes us back to the very beginning of human civilization, helping push early communities in the Ancient Near East toward the domestication of barley. For instance, we have discovered stone beer troughs that are nearly eleven thousand years old at Göbekli Tepe, a site used for ceremonial worship and feasting, predating permanent settlements in ancient Mesopotamia. As brewing developed in this region — a region that includes biblical Israel — it entailed soaking twice-baked barley loaves in tubs and allowing them to ferment naturally, with the help of honey and fruit. The resulting porridge-like mixture would be consumed with straws.

Long before the rise of the mass state and the Industrial Revolution, beer provided one example of the importance of food and drink in shaping a community’s culture. It was one of the most ordinary of cultural products that could be made by the average person in the home, prior to the advent of large breweries and international brewing conglomerates. The origin of brewing, in fact, takes us back to the very beginning of human civilization, helping push early communities in the Ancient Near East toward the domestication of barley. For instance, we have discovered stone beer troughs that are nearly eleven thousand years old at Göbekli Tepe, a site used for ceremonial worship and feasting, predating permanent settlements in ancient Mesopotamia. As brewing developed in this region — a region that includes biblical Israel — it entailed soaking twice-baked barley loaves in tubs and allowing them to ferment naturally, with the help of honey and fruit. The resulting porridge-like mixture would be consumed with straws.

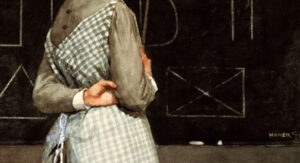

The brewing process as we know it was perfected by monks in Western Europe, taking up the Germanic process of soaking malted barley in heated water to make wort and boiling it while adding flavoring. Monasteries built the first large scale breweries in Europe, created and fine-tuned brewing equipment, and pioneered hops as the main additive to beer, finding it useful not only for its bitter taste, but as a preservative. Nonetheless, brewing was jealously guarded as a household privilege throughout the Middle Ages, with women taking up the task most frequently (at least until the formation of brewing guilds in the late Middle Ages). Beer was the most common drink in northern Europe throughout the Middle Ages, consumed by everyone, including — at a lesser strength — by children. It was seen as a safe, clean, nutritious, and healthful drink, given in monastic hospitality to the sick, the poor, and to pilgrims. St. Hildegard of Bingen summarized the view of the time in her work Causes and Cures (1151): “Beer puts flesh on the bones and gives a lovely color to the face, on account of the strength and good juices of the grain. Water has a weakening effect. . . . Whether people are healthy or sick . . . they should drink wine or beer, not water.”

The medieval view of drinking as health-promoting was coupled with the importance of festivity. With no conception of secularism, eating and drinking took on important roles within the public celebration of faith, alongside processions, music, and dancing. The community demonstrated its faith and pride in its own traditions by thanking God for the harvest and toasting to one another’s good health and prosperity— an act of festivity that Josef Pieper described as the affirmation of the goodness of life. (See his work, In Tune with the World.) Here we see a healthy culture in action, with festivity expressing the primacy of relationships and the beauty of local traditions, and with special clothing, food, and drink testifying to the importance of the holiest days. This kind of communal rejoicing could only come, however, after prolonged periods of abstinence, with fasting from food and drink as a means of moderating excessive attachment and removing impediments to joyful celebration.

Here we see a healthy culture in action, with festivity expressing the primacy of relationships and the beauty of local traditions, and with special clothing, food, and drink testifying to the importance of the holiest days.

Secular culture imparts no such importance to the daily details of life. Eating is just eating. Drinking often becomes an escape from life, not an affirmation of it. Clothes and dancing seek to incite the passions, rather than honor local customs and feast days. Entertainment itself exists completely separate from any deeper meaning and purpose — “it’s just entertaining,” we say, without any thought to how it shapes us from within. This may indicate why large institutions seem to take precedence over daily habits — the large scale, cheap, fashionable, and utilitarian have captured the imagination and moved the center of gravity away from what sits right in front of us. Consumerism, for instance, not only creates passivity to trends, but it also removes us from the cultural vocations to become producers of the goods that shape our lives. It removes us from direct contact with nature, with the work necessary to make nature amenable to human consumption, and from the relationships that enter into work — passive to the exploitation that occurs in the production of goods today.

Culture needs reintegration; therefore, one must take ownership back for one’s own actions and work, and see them as contributing to the good of the community. Brewing, with its ancient cultural roots, can provide one small example. Homebrewing, because it is a return to a central culture practice of the past, stands for more than simply a fun activity. It restores economics to the home, making it a place of production that enlivens it with the same forces that drew people together from time immemorial. Brewing gathers people together for work and for celebration, enabling a true re-fermentation of culture. The same could be said for the craft and microbrewing movements which in the last forty years has taken us from forty to four thousand breweries, creating enhanced craftsmanship and aesthetic appreciation as well as stimulating local economies and cultures through the creation of additional jobs and places to gather. Beer has returned to its rightful place as a locally produced commodity that can, when consumed properly, unite people in conversation and fellowship.

Culture needs reintegration; therefore, one must take ownership back for one’s own actions and work, and see them as contributing to the good of the community. Brewing, with its ancient cultural roots, can provide one small example. Homebrewing, because it is a return to a central culture practice of the past, stands for more than simply a fun activity. It restores economics to the home, making it a place of production that enlivens it with the same forces that drew people together from time immemorial. Brewing gathers people together for work and for celebration, enabling a true re-fermentation of culture. The same could be said for the craft and microbrewing movements which in the last forty years has taken us from forty to four thousand breweries, creating enhanced craftsmanship and aesthetic appreciation as well as stimulating local economies and cultures through the creation of additional jobs and places to gather. Beer has returned to its rightful place as a locally produced commodity that can, when consumed properly, unite people in conversation and fellowship.

Beer has returned to its rightful place as a locally produced commodity that can, when consumed properly, unite people in conversation and fellowship.

Beer cannot save culture on its own, to say the least. It does, however, provide a poignant image of how to return to a productive and festive culture. Putting beer in perspective as a work of culture, integrated within a sacramental view of life, makes it a fitting image for renewal. We can make things and use them as a means of honoring God, living in communion with others, promoting health and moderation, and creating a local economy. If beer can serve as a stimulant of culture, so can many other things. Focusing on beer could seem trite, but, in fact, it helps us to focus on the nature of culture, as the fashioning the goods of creation, and the way in which we can become its creators rather its passive consumers.