Hitting the Mark

A Mighty Hunter of Small Game

Mr. Michael Yost

Through the haze of a long day, a memory of silence and autumn chill, beneath the looming pines of downeastern Maine, returns to me:

Our family vacation home, before the death of my mother’s parents, was on the coast of Marsh Harbor. There are photos in a carefully arranged three-ring binder of my grandfather watching the building underway. The water was delivered from the taps via the lively, if erratic, energies of a sump pump, and the house, while I was there, was never heated by anything other than a wood stove. It was there, during a storm that lasted several days, that I first read (and reread) Moby Dick, one of the few books in that restrainedly decorated house, along with two other favorites: Uncle Remus, and The Foxfire Book. When I was small, I invested whole afternoons in the sport of running and climbing barefoot on the large, grey water-smoothened rocks; and I spent hours plunging about the harbor in a brilliant yellow seagoing kayak, visiting the small islands, watching the harems of seals follow me at discreet distances, and greeting lobstermen, busy at their traps. Later, my wife and I honeymooned there. My grandmother had to sell the house in her final illness, but, as far as I know, a brazen plaque still hangs to the left of the front door, giving the name of the architect and the date of its completion, in Latin.

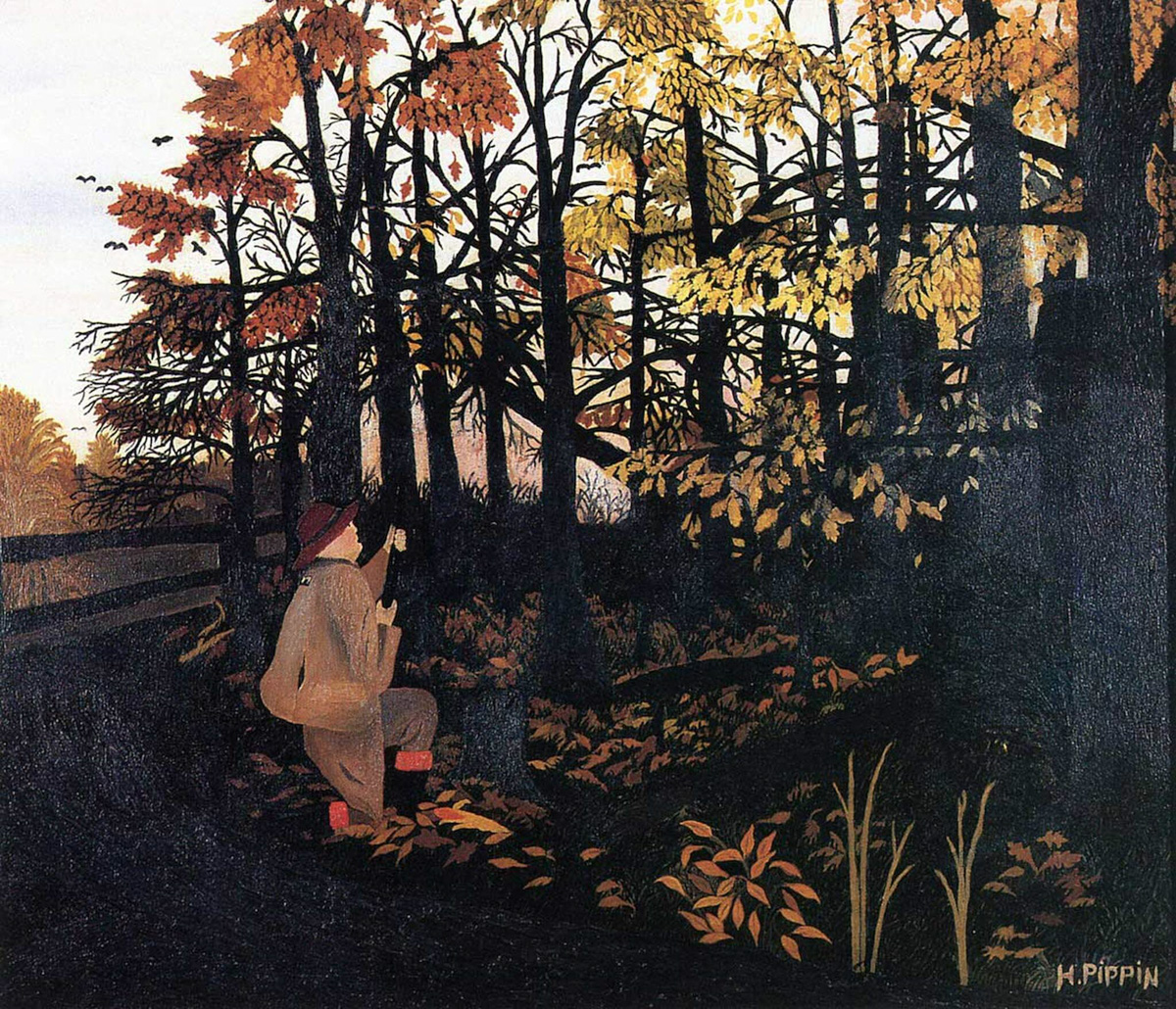

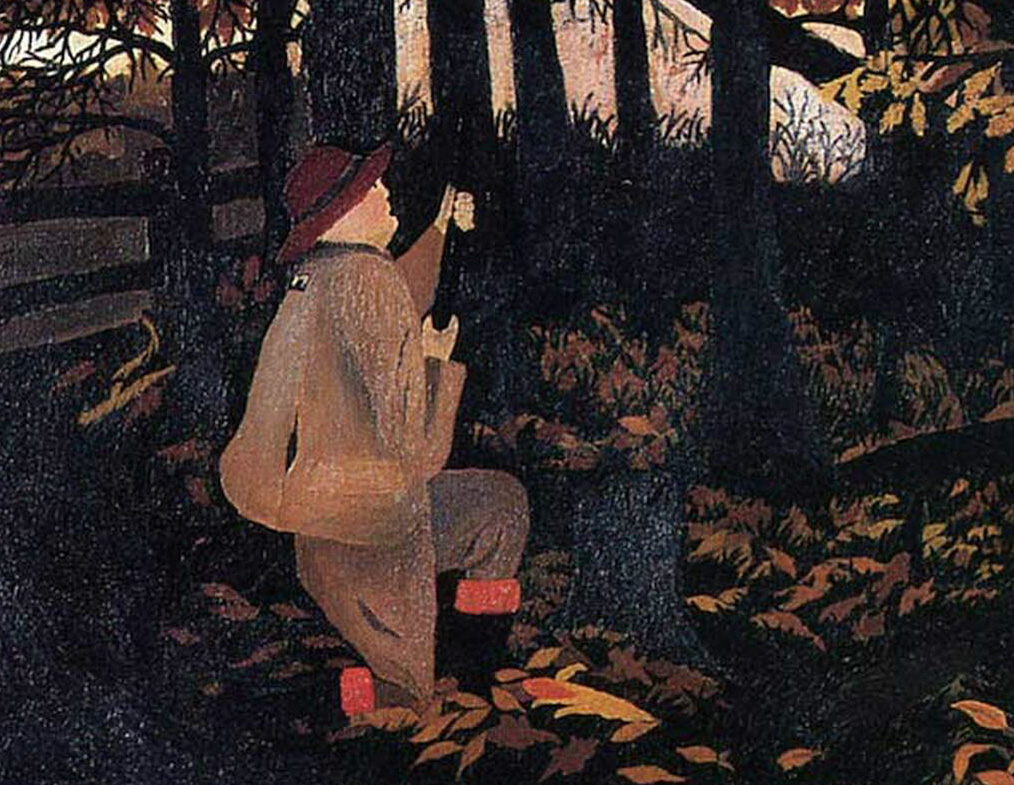

Whenever I smell the rank perfume of seaweed, or smell dry grass in a salt marsh, I think of that place. One year, when I was in my early teens, a neighbor wanted fewer squirrels, and an uncle of mine wanted target practice. So at dawn, about five o’clock, clutching the slender forestock of a .22, I came along, handfuls of little yellow and grey cartridges swelling the pockets of my Wranglers. I remember shooting at small dark shapes in the crotches of trees, their tail-fur haloed by sunrise and the slender morning moon. Eventually, one small body fell away from the tree in a shallow downward arc, landing with a quiet crash in the leaves and bracken.

Whenever I smell the rank perfume of seaweed, or smell dry grass in a salt marsh, I think of that place. One year, when I was in my early teens, a neighbor wanted fewer squirrels, and an uncle of mine wanted target practice. So at dawn, about five o’clock, clutching the slender forestock of a .22, I came along, handfuls of little yellow and grey cartridges swelling the pockets of my Wranglers. I remember shooting at small dark shapes in the crotches of trees, their tail-fur haloed by sunrise and the slender morning moon. Eventually, one small body fell away from the tree in a shallow downward arc, landing with a quiet crash in the leaves and bracken.

It was the first time I remember killing anything, but it seemed a distant affair. Even the crack of the rifle was muted by the thick layers of needles that surrounded us above and below. I could see my breath, and the heat from underneath my sweater fogged my glasses. When I went up to look at my kill, I saw that I had shot the squirrel through the back haunch, and the bullet had traveled up outwards through the torso, dispatching it quickly. We did not eat or even skin the squirrels, at which I was disappointed.

A chance to renew my acquaintance with the squirrel appeared over a decade later, in New Hampshire. At this point, I had been married, become a father, and started teaching at a local academy. I hadn’t been hunting much since that day in Maine, apart from taking potshots at sundry varmints. The change from boy to man seems to have presented itself as suddenly as gunfire. Perhaps the boom and echo of that movement out of childhood resounds through every man’s life, back and forth between the valleys of the years, like the lightning crack of muzzle blast on autumn air.

Perhaps the boom and echo of that movement out of childhood resounds through every man’s life, back and forth between the valleys of the years, like the lightning crack of muzzle blast on autumn air.

I learned some lessons from this more recent outing: The first shot, it seems, is the most important, since it will likely be the only one that hits the mark. In a thick forest, the little fellows can easily escape along the upward path of perilously thin branches, or wind a quick track around a pine trunk, showing itself just long enough for you to recognize where it won’t be by the time your iron sights are aligned.

Fortunately, even if they are fast, squirrels are not strategists. They are loud, chirruping and indignant. Because of this, they are easy to find, especially in numbers. Nor do they seem to give a rap about how much noise you make. When fired upon, a squirrel will move, but he will not always hide. The task of hunting is made easier if hunting is done in a group. The more pairs of eyes and ears, the easier it is to track the shadows of tails across the knotted, angled warp of tree branches that spreads over the blue-grey sky.

Fortunately, even if they are fast, squirrels are not strategists. They are loud, chirruping and indignant. Because of this, they are easy to find, especially in numbers. Nor do they seem to give a rap about how much noise you make. When fired upon, a squirrel will move, but he will not always hide. The task of hunting is made easier if hunting is done in a group. The more pairs of eyes and ears, the easier it is to track the shadows of tails across the knotted, angled warp of tree branches that spreads over the blue-grey sky.

In this spirit, we had invited some friends over. More showed up than were originally invited; with friends, this is one of the pleasant perils of country life. Our household is troubled by an intermittent horror vacui surrounding any surface guests might be able to make themselves comfortable in. In particular, the barn and the guest room bear a lot of wear and tear. Guests have slept in both, sometimes for preference, sometimes of necessity.

As our guests arrived, cases of Mexican beer and red ale started to amass in the kitchen, and eventually, we all trooped outside, men, wives, and offspring. While the ladies amused themselves by letting the young feed the rabbits and chickens, the lads, armed with flannels, tobacco, rifles, and Wellington boots, went trotting around the property, ears perked and eyes peeled for signs of Sciurus carolinensis. A scurry of the creatures, chasing each other and chattering around the high, solitary branches of a stand of white pine, attracted our attention.

. . . the lads, armed with flannels, tobacco, rifles, and Wellington boots, went trotting around the property, ears perked and eyes peeled for signs of Sciurus carolinensis.

Since there were only two rifles, we shot and spotted in turn. As a matter of record, I brought down two, each with a single shot, and the godfather of my eldest son got two as well. These were skinned with the help and guidance of another friend, who hails from Virginia and is steeped in the knowledge of such things. Taking our sharpest kitchen knife in hand, he made an incision beneath the tail and, continuing upwards along the back, degloved the torso and forelegs. He skinned the hindlegs, cutting them and the forelegs off from the torso at the joints, and clipping off the feet at the ankle. It was a well-nigh bloodless affair. One member of our bag was too small to be worth skinning, and so was delivered to the chickens. Darkness began to fall, and we returned indoors.

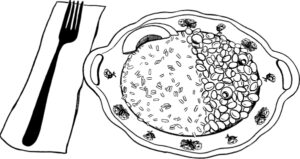

In the sunroom, which was garlanded with string-lights against the early autumn evening, the dinner party was settling itself into wicker sofas and chairs, while preparations were being made in the adjoining kitchen. The legs, at last, were marinated. The bright red enameled saute-pan sent up a cloud of steam that shot sour into one’s nose, as the balsamic vinegar in the marinade started to caramelize and burn, and the outer layer of the meat charred, blackened, and shrunk, revealing a still-tender flesh that had cooked to a firm ivory.

The first bite was lightly crisped without, juicy and nutty within.

Until that evening, I had never tasted this delicious, savory-sized creature, this little clambering succulent, this tiny sachet of flavor. The Fates seemed to have saved it for my years of manhood. It was by no means a full meal, but as winter approaches, and my help-meet becomes more and more willing to bake anything — be it flesh, fish, or fowl — into a pie, I feel that I may yet become, like King Nimrod, a mighty hunter (of small game) before the Lord. Thanksgiving approaches, and I have seen the wild turkeys processing in numbers through our parcel.