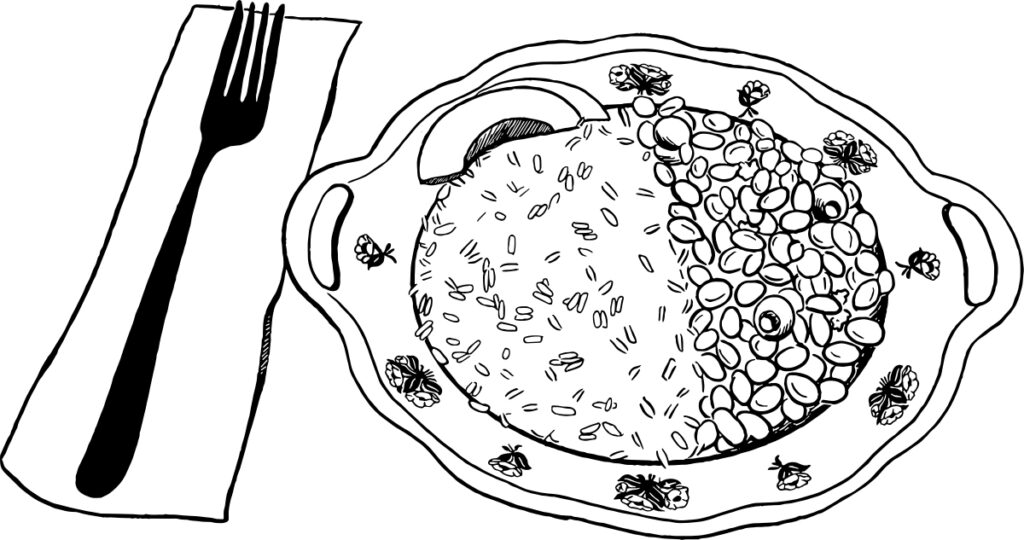

Arroz Blanco con Habichuelas Guisadas

An Introduction to Puerto Rican Cuisine

Mr. Rob Drapeau

I was born at a very young age on an Air Force base in the northwest corner of the smallest (and some would say greatest) island of the Greater Antilles: Puerto Rico. My mom was Puertorriqueña pura, born and raised on la isla del encanto, but my dad was a half-French-Canadian, all-gringo airman from Taunton, Massachusetts. From his side of the family, I inherited a French last name, blue eyes, and an inability to dance. From my mom’s, I received a passionate personality and a preferential option for all things Puerto Rican, especially the food.

Mathematically, I may only be half Puerto Rican, but I figure being born on the island tips the scales a bit, so I proudly claim to be fifty-one percent Puerto Rican. If it’s true that you are what you eat, that percentage shoots up into the mid-nineties.

Puerto Rican cuisine — or comida criolla, as it’s called on the island — is simple, hearty fare. It’s filling, easy-to-make, and delicious. If the only Latin American cuisine you’re familiar with is Mexican food, prepare for a surprise. Because of the prevalence of rice and beans in Puerto Rican food, comida criolla may look familiar, but its flavor profile is more fragrant and herbal than it is fiery and hot.

We ate rice two to three times a week growing up. It wasn’t until after I got married that I realized how unusual this was. Once, my new bride attempted to cook rice in the microwave to save time to disastrous effect. What a mess! It takes about twenty minutes to make rice, no matter how you make it. You might as well make it right.

The recipe below is a great place to begin your Puerto Rican culinary pilgrimage. It is as versatile as it is flavorful and it can be on your table in less time than it takes a pizza to be delivered.

— Rob

Arroz Blanco con Habichuelas Guisadas

(Puerto Rican White Rice and Beans)

Serves 6 to 8

What You Need

Equipment

3-quart aluminum caldero or similar sized Dutch oven

Ingredients

For the rice:

• 4 tablespoons of olive oil, vegetable oil, or butter

• 2 teaspoons of salt

• 2 cups of medium grain rice (look for Calrose rice in the grocery store)

• 2 1/2 to 2 3/4 cups of water (rice should be firm, but not al dente; that’s not a thing)

For the beans:

• 2 tablespoons of oil

• 2 ounces cubed ham (an equivalent amount of real bacon bits will do in a pinch)

• Quick sofrito (Alternatively, if time permits or if you already have some on hand, use Life Changing Sofrito )

• 1 bell pepper diced

• 1/4 cup of cilantro, washed and chopped (remove any woody stems)

• 1 yellow onion, diced

• 4-5 cloves of garlic, minced

• 1/4 teaspoon dried oregano

• 1/4 cup tomato sauce

• 1/2 teaspoon of ground cumin (optional)

• 8 spanish olives, coarsely chopped

• 1 teaspoon of capers

• 4 15-ounce cans of pink beans, drained, or a one pound bag of dried beans, cooked according to bag (see Notes)

• 1 cup (or so) chicken broth, preferably homemade

• 1 small potato cut into 1 inch cubes (optional)

• 1/2 to 3/4 cup cubed butternut squash, pumpkin, or acorn squash (optional)

What You Do

For the rice:

Heat the oil or butter on medium-high in the caldero or Dutch oven. Add the rice and salt, stirring to coat the rice with oil. Once the rice has started to become chalky, add the water and give the rice a good stir. Level it out and then touch the rice with your index finger. The water should come up to your first knuckle (about an inch). If necessary, add a little more water, but not too much. I use a little less water than is recommended so that the rice has a firm texture. If your rice comes out mushy or crunchy, you did it wrong. Use more or less water next time.

Turn the heat to high and bring the water to a boil. After it comes to a boil, turn the heat down to medium and cook uncovered until most of the water is absorbed.

When you can see the top of the rice, turn the rice over from bottom to top with a large spoon. Don’t stir! If you do, the rice will come out mushy, a culinary crime that cries out for vengeance.

Turn the heat down as low as it will go and then cover the pot with a tight-fitting lid. Set a timer for 20 minutes and leave the rice alone. No peeking.

When the timer goes off, turn off heat, remove the lid and fluff the rice with a fork.

For the beans:

Heat the oil in a medium saucepan on medium-high heat. Brown the ham quickly and then add the ingredients included in the sofrito (or a cup of premade sofrito if you have on hand). Saute for 2-3 minutes.

Add the tomato sauce, olives, capers, and cumin (if using), and saute for 2-3 more minutes.

Add the rest of the ingredients, including the potatoes and squash, if using, and stir well.

Cook on medium heat, stirring occasionally, for 20-25 minutes; it should be done about the same time as the rice. Add more chicken broth as necessary to keep the beans saucy, but not soupy. If you’ve included the potatoes and squash, cook until they are cooked through.

Serving:

Ladle the beans on top of or alongside the rice. See Notes for more options.

Notes

Rice and beans are a complete meal in themselves, but this meal is also frequently eaten with fried pork chops, fried chicken, or bistek encebollada — marinated cube steak and onions. It’s also delicious the next morning with a fried egg on top — my favorite breakfast!

Pink beans are the most common beans in Puerto Rico, but you can substitute any kind of beans you’d like and wind up with an equally delicious meal. My favorite alternatives are kidney beans and garbanzo beans. I think pinto beans are a bit mushy, but no one has ever complained when I’ve used them. I usually follow a different recipe for black beans because they don’t figure prominently in Puerto Rican cuisine, but you’re welcome to go for it if you want to use them here.

In my experience, steamed rice from a rice cooker is bland and unimpressive — the oil and salt included in this recipe make the rice chewy and delicious in its own right and not merely a starchy vehicle for delivering beans.

For the full comida criolla experience, leave the rice on the burner a little while longer after it’s cooked to let the rice at the bottom of the pot form a toasty brown crust. This crunchy treat is called pegao, a delicacy that Puerto Rican kids (and sometimes adults) fight over.