Thoughts

Among Ruins

Mr. Thomas Ellen

This, Warren, is our trouble now:

Not even fools could disavow

Three centuries of piety

Grown bare as a cottonwood tree

(A timber seldom drawn and sawn

And chiefly used to hang men on),

So face with calm that heritage

And earn contempt before the age.

—Allen Tate

It is on the hunt where the martial prowess is sharpened, where the techniques of war are seen. On the hunt is man made aware of his heightened sense. This is where his cunning is put on, his aim straightened and ear attuned to the blast and shoulder strengthened for recoil. Where his heart is settled before the squeeze, where his nose grows accustomed to the sulfurous smell and his soul grows to love it. Where these gifts are received from God’s bounty. There is life here, for battles tend to have that effect.

But patience is ever needed. And what is hunting but patience? Even with talent for creation and the ability to observe and study and pass on Nature’s patterns, without the patience to traverse the course of seasons, without the patience to endure a bird flying beyond your gun’s grasp before returning to watch an empty sky, you cannot call yourself a hunter.

Mere thoughts of a novice.

Skimming along water Bible-black with steam rising, obscuring the light of the spotlight I hold, we swing around sharp turns and avoid sunken trees. These waters I have traveled only twice before, far from enough to calm the nerves, not knowing what snares lie beneath. I must put all my faith in my friend more familiar with these parts. We are on his flatboat, not recommended for duck hunting, but with blind and camouflage we can cover up all these white and shining parts. The light does not help as it reflects off the bow, blinding us. Switch it off and the world turns dark. The marsh grass is high and makes this passage ever narrower; it could be thirty yards across or fewer — I couldn’t tell you.

This is Jericho Creek, one of the many tedious ways amid the dug-up canals and trenches, straight and manicured, of South Carolina’s rice country. Here is where the Waccamaw and Pee Dee rivers meet Winyah Bay, which feeds into the Atlantic. Look at it from the heavens and see what was made — as vast an artifact as you’ll find on this continent competes with tumuli of long-lost tribes.

This is Jericho Creek, one of the many tedious ways amid the dug-up canals and trenches, straight and manicured, of South Carolina’s rice country. Here is where the Waccamaw and Pee Dee rivers meet Winyah Bay, which feeds into the Atlantic. Look at it from the heavens and see what was made — as vast an artifact as you’ll find on this continent competes with tumuli of long-lost tribes.

Blocking the entrance to some canals are cypress boards, fragments of a dead time. These are trunks, once used to let the tide in or out when the rice was grown. The British Raj dealt the first blow to these plantations, followed by industrial scale and mechanic operations in Louisiana and Texas, putting these last rice farms out of their misery: Flooding and damage of hurricanes at the turn of the twentieth had taken them to the brink. Now they serve as good public hunting grounds for waterfowl.

It is cold; it is December; it is opening day for all ducks.

What isn’t covered is numb — in my case my eyes and fingers. Textured dark hangs over the marsh, with wind shaking the whole of this. Luminescence from eyes or weed skirts the shore and dips into the murk as we pass. Engines buzz; we glide acute and quick, as spots are taken early on this day.

Textured dark hangs over the marsh, with wind shaking the whole of this. Luminescence from eyes or weed skirts the shore and dips into the murk as we pass.

This area was once swamp, then drained and waylaid and dug and scoured to make the land most coveted. Now, once more, it is the domain of the alligator and owl. Carolina Gold rice, once acclaimed around the world as the best kind of grain, grew here. They’d take the bushels to Georgetown down the river. There were the mills where it was ground from the husk and made ready for eating. Now paper mill-wreak and abandoned steel plant fill the old town. The rice kingdoms, petty fiefs, are long gone and now verboten.

But we are not on a tour. We are here to take part in the great gathering that is opening day.

We hope to beat the crowd but come to find our spot from teal season at the juncture of Little Carr Creek is not safe, there being a boat downrange. It’s a weekday, and these men come out before their shift begins, hoping to get a salvo in before work. They fly around us, standing and holding engine tiller with not a shred of skin vulnerable, scooting atop in boats caparisoned with faux grass and burlap. Dogs stand on the bows, ready for their favorite time of year. We putter around, find a spot where there are few limbs overhead. We don’t want to give nor receive fire, so we take position with our backs to an old rice field.

We are of those internally displaced, who come here like so many others have come here or there for centuries: for reasons of better prospects, for reasons involving pestilence. I call myself a Southerner by way of Richmond, Virginia, now here in Charleston, South Carolina. I and so many others from elsewhere: I can count the number of true locals I have met on one hand. Is this a reflection of my choice of bar and restaurant? Perhaps. Like some new métoikos we are, with some privilege of the citizen.

Charleston should be today the South’s capital, never mind history. Once the wealthiest city in this half of the world, she boasts a legion of founding men. Rutledge, Pinckney, Alston, Rhett, Marion, Moultrie, Manigault, Laurens, Wragg, Middleton, Ravenel, and on and on and so many. These names are found on plaques worn down from exposure of years. Ædes Mores Juraque Curat — for many now just a suggestion.

This town is to be walked, from one end to the other. In spring you stop at one bar followed by two or three more, meeting people as you go, collecting a troop before going to supper at some place featured in a magazine. Some manufactured glamour.

After decades and maybe even a century of futility, of begging tourists for their money, one could daresay upon a glance that the Holy City is due for a renaissance. It boasts the deepest harbor on the eastern seaboard to go along with the thousands upon thousands migrating here. All this money, all this beauty, all this commerce and advertising and adulation from afar and near — Charleston seems close to bursting.

But she is much more a destination — the number one destination according to all those spreads. Yet I do not mean it that way, but in a broader sense — and one not endearing. To be a destination means to be a sight, nothing more than a curation.If you walk South of Broad (or as it was known before realtors renamed it, Below the Drain) when the sun has set in the Ashley, you will find few lights on. These mansions, these once-living homes, are now ornaments for the wealthy elsewhere. An empty city, a city of dress shops, a mall.

Come for the food; come for the horse-carriage tour; come for the City Market to get a trinket. Food and photos and booze-addled bachelorettes. Watch the girls stand in front of Rainbow Row with pursed lips in a sundress just bought from Lilly Pulitzer. Boutique hotel here, bed and breakfast for the elderly couples there. Rooftop bar sued into oblivion, but they still operate and serve cocktails for the price of a meal. But do come try the latest dish, this one inspired by fusion of this and that or another from anywhere else but here.

These mansions, these once-living homes, are now ornaments for the wealthy elsewhere. An empty city, a city of dress shops, a mall.

Man is ever the same. Populists of yore once rallied the countryside in South Carolina against the decadence of the planters in Charleston, against the merchants and lawyers. All their money and land and slaves made rough going for the freedman or lowly artisan. The war and Reconstruction brought the elites down a few notches, sure, but the final nail would be the Irish taking it to the Broad Street Ring in the early twentieth century, ending the reign of the Anglo-Saxon. But what is municipal pride in this age? Our inscrutable ruling class — that which sets the tone — congregates in cities, no more country squire rule. There is no longer an outward appearance conspicuous enough to see. It is their beliefs and language that make them members; it is the lifestyle they live. Portents abound here: an average public college and an expanding culinary scene bring with them the insufferable uniformity of everywhere.

I left Richmond after it was torched in the summer of 2020, burned by the same multiplying here. I watched from afar in my new home as what made it unique was stripped down: those fine bits now paraded as spoils of war, as icons of conquered gods. As for here, Calhoun found himself on the move again. Not as he once moved from one cemetery of Saint Phillip’s to the other, concealing him from Union troops, but his bronze likeness taken down from his perch in Marion Square. We are both of us — and all of us — displaced. Which piece of the world is home? Which place is mine? Which fight is mine?

Perhaps, ultimately, nothing is mine. Perhaps that is as it should be. I am in this place but not of it, and the battle is mine sayeth the Lord, and there is mourning and hope and relief in that. You don’t get a proper understanding of it until you stand on the embankment; it just won’t register until you stand on these mounds, this great ruin.

I jump to shore from our boat, ready for shooting light. Brambles and roots line it and cut my palms as I grab hold to ensure I don’t slip. Spread out in waning darkness is the field, now holding brush and small trees, which stretch on for what could be nearly a mile. They had rows of slaves plant seeds here, avoiding snakes and the like. Ditches of various depths lined these acres once, draining water as need be. They’d wait until the proper time to raise the trunks, to let run in water at the perfect height. In April they’d sow. Once done, the sluice gates would rise and the fields would flood. More fieldwork. More flooding. More draining. If the water is too high or too low, the year will be lost.

Ricebirds would come in, the bobolink most prominently. Ducks and geese would dent a profit too. Trusted men stood watch, gun in hand, to expel this nuisance, those flocks that extinguish your shadow. In entries describing these times, before and after the war, guests would be asked what kind of bird they’d like for supper — summer duck or teal or pintail or canvas-back. Without any deviation, these men would bring back rice-fattened birds of your choice.

Their intricacies traced in tall grass, under brush, on sand or mud. Alligators can snatch a dog, we’ve been told: don’t bring a dog for teal season in the late summer and fall lest you want to watch a gator get them. Wait until the winter when they crawl into warmer places.

Their intricacies traced in tall grass, under brush, on sand or mud. Alligators can snatch a dog, we’ve been told: don’t bring a dog for teal season in the late summer and fall lest you want to watch a gator get them. Wait until the winter when they crawl into warmer places.

All these creatures lowly or high emerge or soar into these tracts — always returning, coming back at their appointed hour. No matter if untouched or configured to our reason, then left behind after war or maelstrom, these many always come back to this marshland.

And so we sit and wait, watching the skies, and ducks fly over us as if knowing it’s not yet time. The water stirs with fish. Our legs grow sore from the strain of kneeling. More fly over but from behind this time, silent and fast, and we wonder if we will ever hit them at that rate they’re going. Birds awaken and sing, twittering and holding onto grass. Seconds are drawn out and tension screwed in passed flush. It seems the light approaches all at once, ten minutes rung out in short time.

The earth is grey in this new light. Deer stumble in the marsh, by the placid dark river with a current strong enough to carry you off. With millesimal precision, the cacophony erupts at the exact point of the sun’s rising, and all the world is drowned in the barrage from lottery-won fields. The tree over there (that hosted the owl you saw perched in the dark) could fall, and you would find it muffled for all the fire, this great unleashing. We laugh at our envy and imagine the joy and suffering this fusillade brings.

The earth is grey in this new light. Deer stumble in the marsh, by the placid dark river with a current strong enough to carry you off.

They must’ve watched them come in before the light in their blinds and picked out that one from this and told themselves they’d reach the bag limit before a quarter-hour passed. But soon we rise at their passing and send up our shot making hostile their entry. Empty shells roll metallic on the fiberglass. The rumbling growing and coughing, belching of the latest kind of Beretta or Remington: you wonder if anyone has their plug in because that was much more than the three shells allowed in a gun from that one.

Like some Bernard Baruch they must be, fat and happy. Hundreds of these passersby lie in heaps around them. Thank the Northern industrialists who bought these defunct plantations and made them sanctuaries, some respite from the stock ticker. Chide them for having no limit then, as profligate as your aim allowed. Blame them for your empty bag. You could take a dozen with a single shot, so vast their number used to be. But it was restoration of a dead land by way of hunting, bringing presidential envoys and those hoping to find a more natural world amid this conquered nation. A more peaceful invasion, another kind of violence inflicted, one toward our better nature.

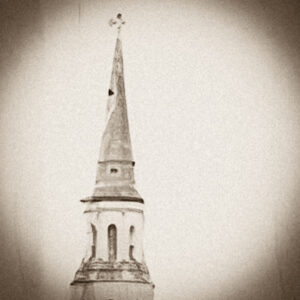

If this land was dead, then what of Charleston? The story is not over, not all slowed and fat and happy, not all done seeking some greater calling. There is a fight here won. Saint Phillip’s and Saint Michael’s, two grand prizes, were recently given to their rightful owner: the Anglican Church of North America. These happy warriors fended off the Episcopal Diocese, who wanted to turn these sanctuaries into pulpits of the civil religion. The attendance has never been stronger and, though not myself a parishioner, I feel pride at the closed doors barring entry for tourists. There is life here, for battles tend to have that effect.

If this land was dead, then what of Charleston? The story is not over, not all slowed and fat and happy, not all done seeking some greater calling. There is a fight here won. Saint Phillip’s and Saint Michael’s, two grand prizes, were recently given to their rightful owner: the Anglican Church of North America. These happy warriors fended off the Episcopal Diocese, who wanted to turn these sanctuaries into pulpits of the civil religion. The attendance has never been stronger and, though not myself a parishioner, I feel pride at the closed doors barring entry for tourists. There is life here, for battles tend to have that effect.

The hours pass, and we listen and watch through holes in the blind. Most ducks fly just beyond range. None come to our decoys. We are not positioned well, not knowing their routes. We agree that if we manage to snag two or three in a passing we will set off with them. But no such come close enough. Yet over and above are dozens together. When will they stop — after a hundred years of no Gold Rice here? Settling for corn for how long? Have they lost the refined tastes of those before them? When will any of it cease? They say the South is known for clinging and salvaging, but you look over this and see that’s just a natural pattern. What was once before will be again, but slightly different, whether for better or worse. Nothing is ever lost.

The surroundings have gone from grey to dead yellow. Shots are now sporadic. Duck boats pass as men have bagged their catch and must clock in at work. The owl is replaced by a hawk, slowly looping just feet above the marsh, not bothered by the shooting. A DNR agent pesters us, asking for stamps and licenses and for us to unload and if we have plugs and if we have ducks — and what kind of ammo y’all got? No birds, steel ammo, no lead, and we got all the rest. We agree to reload after he buzzes off to fine someone else, and as my cold fingers slip in the first shell, I am beat to it.

Down down down, he swings his gun to the right in perfect tracing and blasts above, with my eyes peering through the blind watching a flawless shot on a wood duck — alone, once-sailing, falling dead in the air to the water. A brilliant shot, but not mine.