Undisturbed

Mrs. Gina Loehr

Our barn collapsed in the winter of 2008. It was a brand-new building. We hadn’t even moved the cows in yet — that was scheduled for the next week. My husband Joe and I woke up on the twelfth of December and saw from across the field that the roof of our new forty-thousand square foot milking barn had completely caved in under the weight of the night’s snowfall. We stood there at the dining room window dumbfounded, staring in shocked silence.

Then, I got angry.

We had hired some younger builders to complete this project. We trusted their workmanship, but clearly they had done something terribly wrong. I wanted to sue. I’ve never wanted to sue anyone for anything in my life, but I was furious, and in spite of the insurance coverage that would protect our investment, I wanted retribution. Joe and his brother Mark — his partner in the farm — responded differently.

“It could’ve been worse. No one got hurt. No animals were lost,” Joe was able to point out right away. Mark spoke in a similar vein when we talked. “God was looking out for us” was the sort of sentiment these farm boys expressed. I, on the other hand, was looking for vengeance.

“God was looking out for us” was the sort of sentiment these farm boys expressed. I, on the other hand, was looking for vengeance.

Sure, nobody was killed, but they could have been. Now our timeline was irreparably messed up. Even if things could be rebuilt, it would be worse than starting from scratch with such a massive clean-up job. This building company didn’t deserve to be in business, and I was ready to make sure the people who owned it never got another job. I told Joe how I thought he should proceed. He didn’t listen. Or, at least, he didn’t agree.

He called to share the news with the man in charge of the project, who was equally stunned and flabbergasted. But Joe didn’t accuse, he didn’t yell, he didn’t demand. After the dust had settled and the rebuild was ready to be discussed, Joe forgave the builder and brought them back to finish the job.

I couldn’t believe it.

Of course, they did things differently the second time around. A third-party engineer was hired to assess the initial collapse and redesign the structure. Apparently, it was not so much a question of workmanship as it was design. The project finally came to fruition, and that barn has now survived more heavy snowfalls than I care to count. In other words, everything worked out just fine. And in Joe and Mark’s minds, it always does.

Of course, they did things differently the second time around. A third-party engineer was hired to assess the initial collapse and redesign the structure. Apparently, it was not so much a question of workmanship as it was design. The project finally came to fruition, and that barn has now survived more heavy snowfalls than I care to count. In other words, everything worked out just fine. And in Joe and Mark’s minds, it always does.

This is one of Joe’s traits that struck me from the first time I met him. A kind of solid, immovable peace that I had never encountered in anyone else radiated from this dairy farmer. Nothing seemed to ruffle him. Now, thirteen years into my life as his wife, I remain convinced that he and his brother are the most unruffled people I have ever met. I have a theory about why.

They are not stoic or emotionless folk, but they are able to accept whatever comes and trust that — through a combination of hard work and prayer — everything will all work out in the end. There is a plaque hanging up in my mother-in-law’s house that reads, “It is what it is — but it will become what you make of it.” This was the soil in which these boys were planted. I believe their peace in the midst of any storm comes from being farmers.

There is a plaque hanging up in my mother-in-law’s house that reads, “It is what it is — but it will become what you make of it.” This was the soil in which these boys were planted.

For all of the technological advances in soil management, harvest productivity, and veterinary services, and all the genetic progress being made with animals and crops, there are still two factors in the life of a dairy farmer that simply cannot be controlled: weather and death.  A farmer may have the most amazing field machinery — like a three-hundred fifty horsepower tractor driven by GPS that doesn’t require human steering or a chopper that can harvest three-hundred tons of corn in twenty minutes — he may have the most impressive herd of cows with valuable, proven genetic traits for longevity, milk production and calving ease — but he cannot bring down the rain when the land is too dry or bring up the sun and wind when the fields are too wet. He cannot control the occasional loss of an animal due to a genetic abnormality or an inexplicable health problem. In spite of his best efforts, his skill, and his assistance, some calves are stillborn.

A farmer may have the most amazing field machinery — like a three-hundred fifty horsepower tractor driven by GPS that doesn’t require human steering or a chopper that can harvest three-hundred tons of corn in twenty minutes — he may have the most impressive herd of cows with valuable, proven genetic traits for longevity, milk production and calving ease — but he cannot bring down the rain when the land is too dry or bring up the sun and wind when the fields are too wet. He cannot control the occasional loss of an animal due to a genetic abnormality or an inexplicable health problem. In spite of his best efforts, his skill, and his assistance, some calves are stillborn.

And life goes on. The rain eventually comes, as does the sunshine. The herd continues to grow, in spite of losses along the way. Even though the yield changes from season to season, there is a harvest every year. Maybe it’s the result of continuing a business that has been in the bloodline for nearly a century and a half. Yes, some years are lean — too many, in fact — but no storm, no bovine illness, no disaster has proven so disastrous that it could not be overcome.

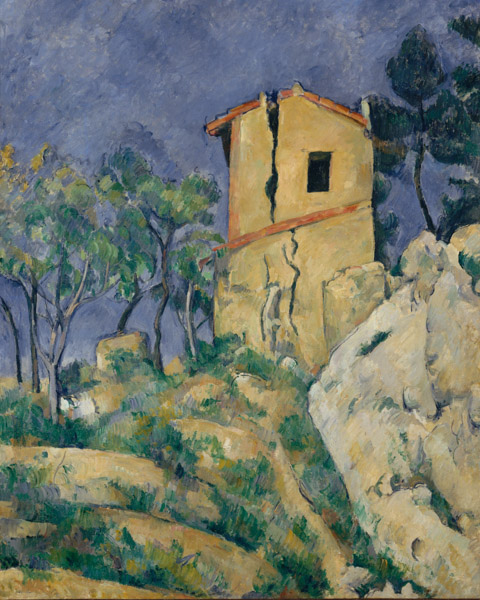

Weather and death teach the farmer, over time, that, ultimately, he is not in control. He must bow to forces beyond his (remarkable) strength. This posture of humility, regularly assumed, teaches him to be flexible and free. He is a reed that remains rooted in spite of the wind because it has grown tall, always swaying with the breeze, not resisting it in a futile effort to overcome its power. He is a bird that soars on the gusts, taking them as they come, instead of wasting his time sitting on the ground wishing he could go farther, faster.

The storms will blow, no matter our profession, our position, or our posture. The only question is whether we will respond by grumbling against the wind, or by floating upon it, our hearts undisturbed.