Daedalus & Icarus

A Cautionary Tale About Parenting

in an Age of Technology

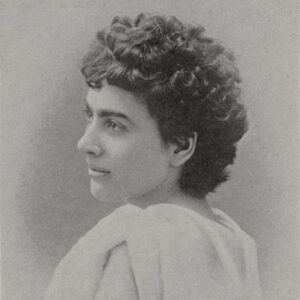

Dr. Nadya Williams

Premium Subscribers

Sorry, this feature is only available for H&F Print Premium subscribers. You can sign up here.

(If you are already a Print Premium subscriber, be sure to click the authentication link you were sent by email so this won't happen again.)

Don’t fly too close to the sun. We have all heard this advice and, likely, the tale of hubris that inspired it. But it seems that whenever we focus on the tragic death of the one who flew too close to the sun, we forget that the story is not just about him, the child. The story is, rather, about the relationship of a father and a son. And it is, no less than that, a cautionary tale about parenting and the use of technology. It is a tale as old as time.

Perhaps the entire history of humanity is, first and foremost, the history of technological inventions and advancements, as the Greeks thought. In the “Ode to Man” in Sophocles’ tragedy Antigone, the chorus of city elders marveled over everything people have accomplished and invented over the ages, all to make their lives a bit better. Agriculture, building, seafaring. Yet we know, as did the Greeks, that inventions and technological advancements always carry risks, too. We must remember that some of the powerful inventions that we think will save us can destroy us, too. And so the tragic story of Daedalus, one of the greatest inventors in all of Greek mythology, and his son Icarus reflects well the challenges of modern parenting, especially when it comes to the use of ever new and advancing technology.

And so the tragic story of Daedalus, one of the greatest inventors in all of Greek mythology, and his son Icarus reflects well the challenges of modern parenting, especially when it comes to the use of ever new and advancing technology.

Maybe it is worth taking a step back and re-telling the familiar story in full.

There was a father once. A legendary inventor and tinkerer, he found himself in a seemingly inescapable situation. Trapped in a remote prison on an island with his young son, he devised a revolutionary technological device that would allow them to escape to freedom. He carefully, painstakingly trained his son in using this device, a set of wondrous wings, modeled on those of birds, but capable of carrying the much heavier humans. At last, on the appointed day, each of them put on his own device and activated it. This allowed each one to transform for a time from a creature of land into a creature of the air — oh, the wonders of defying nature through human genius!

Daedalus’ invention of wings is in some ways a strangely transhumanist technology. But then, Greek mythology is filled with such transhumanist dreams — the desires of people who knew they were physically weak, susceptible to illness and death, and living in an environment that seemed unpredictable and at times downright cruel. Wouldn’t it be great to break out of the human body that is bound to die and be turned into something more powerful? Except for the fact that, in mythology, such dreams of escaping the frail human body always result in tragedy. Transformation into something else in Greek myths is usually the result of a curse, not a blessing: the result of punishment or persecution by the jealous and petty pagan gods. Niobe turned into weeping stone, Daphne a laurel tree, Acteon a stag that was promptly hunted to death.

Wouldn’t it be great to break out of the human body that is bound to die and be turned into something more powerful? Except for the fact that, in mythology, such dreams of escaping the frail human body always result in tragedy.

But at least Daedalus seemed to defy these odds. He and Icarus fled — flew! — from captivity on their wings. Defying human nature, these wings empowered the father and son to transform into something other than mere human — something more powerful, and most important, free.

Yet freedom obtained with this invention came with a cost. One had to be cautious when using this technology. For to abuse it would lead to certain death — literal, in this tale, rather than figurative. And so tragedy struck. While the father was wise enough to know how to carefully employ the device he had created, the son had no such constraints. Soaring in his joy too close to the sun, he relished the incredible feeling of flight. Alas, the heat from the sun promptly melted the wax holding the fragile wings together, and Icarus plummeted to his death in the merciless sea below.

In parenting, of course, we should never expect things to go smoothly or perfectly — this is especially the case when we entrust children, these unformed beings with a level of wisdom at best commensurate with their young age, with technology. Daedalus, of all people, perhaps should have known better than others of the dangers of his inventions — his original prison, after all, was a labyrinth that he himself had created on commission.

As to the technology, is technology in and of itself something neutral and potentially trustworthy, and only our uses of it render it good or bad? Or is it something that we should trust less than we do? These are questions to which the story of Daedalus and Icarus readily suggests alarming answers. While the technology that Daedalus employed differed in its way from devices we readily pack into our homes and trustingly place in the small hands of increasingly younger offspring, it came equipped with the same hazards. Using it correctly and moderately — flying at just the right altitude — meant survival. Using it too recklessly meant sure death. How do we know that children or teenagers, unpredictable as they can be at times, with their developing (but not yet fully developed) brains and reasoning abilities, will stay safe when using technology that we have taught them to use? We don’t. We just hope for the best — as Daedalus did.

As to the technology, is technology in and of itself something neutral and potentially trustworthy, and only our uses of it render it good or bad? Or is it something that we should trust less than we do? These are questions to which the story of Daedalus and Icarus readily suggests alarming answers. While the technology that Daedalus employed differed in its way from devices we readily pack into our homes and trustingly place in the small hands of increasingly younger offspring, it came equipped with the same hazards. Using it correctly and moderately — flying at just the right altitude — meant survival. Using it too recklessly meant sure death. How do we know that children or teenagers, unpredictable as they can be at times, with their developing (but not yet fully developed) brains and reasoning abilities, will stay safe when using technology that we have taught them to use? We don’t. We just hope for the best — as Daedalus did.

This hope, alas, often proves our undoing, just as for Daedalus. I am reminded of the clichéd advice or congratulations that we (and Hallmark cards) too often offer high school and college graduates: We wish that they will soar to new heights or soar to their dreams. The language vaguely echoes Isaiah 40:31, describing that “those who hope in the Lord will renew their strength. They will soar on wings like eagles.” But in these congratulatory words, God rarely comes up — instead, we get a transhumanist blessing, a wish that our children, as they go forth to new milestones in life, would achieve something so great as to seem impossible for mere mortals.

What if instead of dreaming of transhumanism for ourselves and our children, we focus on relationships with these imperfect humans in the here and now? When we as parents propose technological solutions to everyday problems, we inadvertently encourage this way of thinking further for both ourselves and our children: people and God are not enough to help with whatever this challenge is; you need something more powerful. Just as Daedalus resorted to a technological solution even as his prison — the labyrinth — was actually a problem of his own creation, so do we resort to more technological solutions to the technology-inspired problems of our age.

Just as Daedalus resorted to a technological solution even as his prison — the labyrinth — was actually a problem of his own creation, so do we resort to technological solutions to the technology-inspired problems of our age.

Feeling bored? Here, play this game on mom’s tablet. Want someone to read you a book? Well, here, let me get an app to read it out to you. Curious about something? Here, look it up on Google — on my phone. Still bored? Watch this movie for the next hour or two.

Sometimes we really cannot drop everything to read a book to a child or entertain said child in the active way he or she wishes. Yet replacing relationships with technology sends a powerful unintended message to the little ones whose minds and souls we are shaping with every action and decision we make. And so, what I am worried about is the cumulative effect of the constant everyday trickle of us trusting technology to solve our problems — for both parents and children — over the course of days, weeks, months, years. The end result cannot help but erode bonds, encouraging people to spend more time engaging with technological companions than real ones, in the process corrupting individual souls and family relationships.

The overwhelming rat-race-style busyness of modern life is a reality, but we do not have to accept it so readily as our default. It is never easy to resist the pull of gravity, but what if we designed our own homes, our family’s lives, with relationships in mind, instead of looking for technological escapes and shortcuts to avoid relational interactions when we feel like we must do something else?

The overwhelming rat-race-style busyness of modern life is a reality, but we do not have to accept it so readily as our default. It is never easy to resist the pull of gravity, but what if we designed our own homes, our family’s lives, with relationships in mind, instead of looking for technological escapes and shortcuts to avoid relational interactions when we feel like we must do something else?

It is convicting to realize that too often we seek complicated answers rather than simple ones that have been there all along. And so, what if a child’s request for reading yet another book always came first? A quest for radically human flourishing in our own lives and homes could begin with such a small change as this.