Paper Routes

Working Hard & Humanely

Mr. Paul Schweigl

My son recently turned seven, which puts him just beyond the halfway point to the age when I expect he will begin giving serious thought to having a job of some kind. I will counsel him to consider the opportunity costs involved with regular employment during high school, but I am not going to stand in his way. My wife’s family farms, so the lad will be able to work as much or as little as he wants, whenever he wants. What is more, there is little risk of him being treated like a mere cog in a vast machine or forced to violate his conscience in order to remain employed when his boss will be someone he calls Grandpa. Fathers want to have things in common with their sons, though, so I cannot help regretting that he will not get to break into the world of work in exactly the way that I did, some decades ago: schlepping the fruits of the fourth estate.

My brother (older by two and a half years) got his first paper route once he turned twelve. It was for the local shopper, which ran Wednesday and Sunday editions each week. All told the route covered around one hundred and fifty houses and a few businesses in our mainly-middle class neighborhood in Manitowoc, Wisconsin. Since this included both sides of almost every street in the neighborhood, I was drafted immediately (and somewhat willingly) to deliver papers on whichever side of each street had fewer subscribers. One of our parents would take us out on Tuesday and Saturday nights, dropping us at one end of each road and then picking us up again at the other, for the forty minutes or so it would take us to finish up. I typically spent most of those minutes trying, with dependable futility, to keep up with my brother.

Like any empire, ours felt compelled to expand. My brother added a second route within a year: a thirty-five-paper daily route. When I turned twelve, I got two daily routes of my own (about seventy houses total), and then my brother added one more daily route to cap things off once and for all (the four daily routes covered almost exactly the same ground as the shopper route). Every day we delivered one hundred and fifty papers and added the one hundred and fifty copies of the shopper two nights per week to boot, which does not count the subbing we would often do for other carriers. It was quite an operation at its peak, with Saturday evening’s routes (the shopper and the Sunday daily) occupying about two hours of our time. We never finished before 1:00 a.m. As the relentless news cycle marched onward, even the foulest of weather could not stop us from playing our part. Everything, including our holiday celebrations, evolved to make room for delivery time.

We never finished before 1:00 a.m. As the relentless news cycle marched onward, even the foulest of weather could not stop us from playing our part.

Most of our daily customers sent payments directly to the newspaper’s office, but there were always a handful of families from whom I needed to collect. The reader can decide if $6.30 seems like a lot of money to pay each week for a local paper in the early 2000s, but for at least a few households in my neighborhood, it really was. One middle-aged ne’er-do-well used to scream (think full-throated) every time I would knock on his door. Once, when he owed me nearly twenty dollars, he reached into his pocket and found only two dollar bills and about six wooden tokens from a tavern downtown. I did not take the two dollars or the tokens. Eventually, his brother, who lived in Milwaukee, made stopping by my parents’ home to settle up with me a routine part of his visits to his brother. For another house, I learned to time my collection stops to the rhythm of the family’s paycheck cycle.

I do not think paper routes such as mine would have troubled Pope Leo XIII very much, but there certainly are those who criticize newspapers for their traditional reliance on the labor of the young. Those critics may have a point, but they did not get to see the way my family always worked together to get the papers delivered. Even in those ugly and awkward teenage years when my brother rarely spoke to me, he and I worked together just fine in order to carry out the day’s work. We subbed for each other when we were sick, and our parents always helped us with the shopper paper, the Sunday daily, and the difficulties of getting the papers delivered by 5:00 p.m. when we had school and sports practice immediately afterward. It was not a highly lucrative operation, but we did it as a family, and I would not trade the memories. Even our little sister used to walk alongside me from time to time. Once I swatted an aggressive dog with a paper, fearing that it might bite her. The owner’s neighbor saw me hit the dog and came out to administer one of the finest scoldings I ever received. I would do nothing differently.

My friends loved the routes. We were a restless lot, but every day there were papers to deliver at the Schweigl household, which meant that we had a dependable source of something to do, which seemed an awfully precious commodity in those days. The weekend routes, in particular, were a hit among my chums, since it meant walking around at night without any adults keeping an eye on us, as my parents would stay home if there were enough of us to carry all of the papers at once.

Though the word “neighborhood” often seems anachronistic these days, I literally knew the name of everyone in mine: either their names were on our list of subscribers, or my mother (a postal worker in good standing with the Church and the USPS) would fill us in about who dwelt in the few houses that did not get even the free shopper. My father, a police officer, gave me strict instructions about which customers on my route I was not to speak with (a prohibition that proved impossible on at least two occasions, including once when a multiple felon from the neighborhood rode his bike alongside me, chatting for nearly a full hour during the early morning). I duly noted where all the pretty girls on the route lived (which, alas, did me no good), and I also learned which folks were lonely. One widower spent half an hour one summer morning showing me his fleet of three classic cars. Another customer, in his early nineties when I began delivering, was almost entirely blind. I do not know what he did with the newspaper once he had it, but every day he made what appeared to be a long, difficult walk from his chair to the front door to retrieve it. He was memorably friendly every time we spoke. When he died his son sent me a check for ten dollars.

He was memorably friendly every time we spoke. When he died his son sent me a check for ten dollars.

One Saturday morning, probably in 2002 or 2003, I discovered that someone had left, at the end of several dozen driveways on my route, a rubber-banded document, obviously printed on someone’s home computer, that blamed the Jews for September 11th. I gathered as many as I saw, brought them home, and burned them. For the next four years, I fancied myself something of a neighborhood sentinel, keeping a solitary vigil on behalf of the public good.

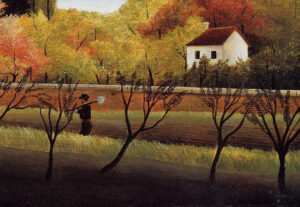

I was already in love with churches for their beauty and essential warmth, but I did my best praying on the paper route. This was especially true when we delivered at night. On even mostly overcast days, a pillar of cloud might be hard to discern for the people in the back. A pillar of fire, though, is always going to make an impression. To put it another way, there is just something about the nighttime. God could see me no more clearly at night (Ps 139:12), but teenaged me could, alone at night, somehow see more clearly that God could see me clearly. My prayers, as I prowled the sidewalks during those heady years, should have been heavy on repentance, but repentance always took a backseat to gratitude. This was not gratitude for any of the most obvious blessings in my life, but simply the kind of gratitude that came from marveling that there should be nights like this one, and that I should get to be a part of it. Maybe you needed to be there.

I hope my son finds a job where he can feel alive in exactly that way. I would never claim that the paper routes were a vocation, but I always had a sense of purpose and a sense that people benefited from the work I was doing. I think what I am really hoping for is that the lad’s first job will teach him everything that my paper routes taught me. Work ought to help reveal the dignity of the worker, while enmeshing him in a community where he can learn to be a stronger but also more compassionate man. I pray he will feel some of the same familial intimacy I did when my brother and I loaded up all of the papers in our parents’ Chevy Blazer and sallied forth. I pray that working will somehow integrate him into a community where people know and support one another, and he will feel a certain protectiveness toward them. If it is not too much for this father to hope for, his work may even give him an opportunity to see where he might be uniquely able to support others as they shoulder whatever burdens they happen to have. Delivering newspapers managed to pull all of that off for me. If his teenage job can check all of those boxes, he will know a good deal about what it means to work hard, and also humanely.