An Interview With Dr. Allan C. Carlson

Dr. Allan C. Carlson is a historian and international lecturer on the topics of family, agrarianism, distributism, and economic liberty. He is the author of numerous books and a contributor to more than fifty compilations. He wrote the recent H&F essay “Land, Limits, and the Scandal of Reparations.” Mr. Rory Groves is the author of the remarkable book Durable Trades (see our review). Dr. Carlson’s works on the natural family and agrarianism were highly influential on Mr. Groves as he was contemplating and writing Durable Trades, and Dr. Carlson penned its insightful foreword.

The two gentlemen share below a written exchange, exploring life, agrarianism, and Third-Way ideas. Mr. Groves wrote questions from his small farm in Minnesota, and Dr. Carlson responded from his small farm in Illinois.

Rory Groves: What originally piqued your interest in the agrarian movement?

Allan Carlson: I grew up in Iowa during the 1950s and ‘60s. While by and large a suburbanite, farm questions still permeated the state’s culture in that period: from crop price reports on most of the radio stations to the then already legendary Iowa State Fair. Then I married a farmer’s daughter, whom I met at Augustana College (Illinois). Betsy’s father had been very active in the Farmers’ Union, an agrarian alliance to defend family-scale agriculture. At first, I was under the influence of free-market libertarianism and couldn’t understand his rear-guard battle against capitalism. Then my sister gave me a copy of Wendell Berry’s masterpiece, The Unsettling of America: Culture and Agriculture. On my first read, I furiously scrawled question marks in the margins of the book. Then, in the wake of the farm crisis of the early 1980s, when many family farms failed, I read it a second time . . . and replaced almost all the question marks with affirmative exclamation points.

RG: What is “distributism” in layman’s terms?

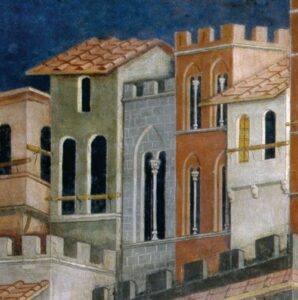

AC: Distributism is an economic system that celebrates the small and the human. It rests on strong home economies and seeks the widest possible distribution and ownership of productive property, particularly farm land. For necessarily larger enterprises and machines, it favors worker ownership through cooperatives. It seeks and reinforces local communities, bound together by ties of kinship, faith, and trade. It welcomes lifelong, fertile marriages of women to men. It favors home care for the elderly and infirm and home-centered education for the young.

AC: Distributism is an economic system that celebrates the small and the human. It rests on strong home economies and seeks the widest possible distribution and ownership of productive property, particularly farm land. For necessarily larger enterprises and machines, it favors worker ownership through cooperatives. It seeks and reinforces local communities, bound together by ties of kinship, faith, and trade. It welcomes lifelong, fertile marriages of women to men. It favors home care for the elderly and infirm and home-centered education for the young.

RG: Does agrarianism have any relevance in this day and age? Isn’t it an antiquated idea?

AC: Agrarianism remains relevant for anyone who seeks a humane and sustainable economy. The economic recession of 2008/09 revealed the corruptions that are endemic to finance capitalism: millions lost their homes and savings while dishonest bankers escaped any punishment. Even the “healthy” neo-liberal capitalist order of the subsequent decade rested on an ever-widening inequality, with the great majority locked in a servile state, without any ownership of property. The “Covid-19 Recession” has shown the fragility of a “globalized” economy. Remarkably, the strategy for survival around the globe has been a reuniting of workplace and home, a return to home gardens, backyard chickens, and other forms of home production, a turn to home schools, and so on. Agrarianism/distributism, we learn again, is the natural human economy.

The “Covid-19 Recession” has shown the fragility of a “globalized” economy.

RG: What path exists to move towards an agrarian/de-centralized future? Give some hopeful examples for this movement.

AC: At the level of law, we need “trustbusters” like good old Teddy Roosevelt who will break up monopolies and great corporate concentrations of wealth, land banks that will assist farm tenants to become owners, prohibitions on the corporate ownership of farmland, local credit unions enjoying favored regulatory status, sound financial support for family homes on lots suited to home production, legal encouragement to producer and consumer cooperatives, and an end to federal farm policies that favor big producers. At the local community level, the recent growth in community-assisted agriculture, farmers’ markets, and “local foods” should be encouraged through careful subsidies and favorable tax treatment. Suburban zoning laws and antiquated “housing covenants” that prohibit gardening and the keeping of chickens should be scrapped. The examples and stories of families that have successfully “refunctionalized” their homes and so gained their independence should be celebrated.

RG: How can the average family get started? What if a family wants to farm but can’t afford to buy land or leave jobs in the city?

AC: Tomato plants in pots on an apartment balcony can be the first step to liberation. The practice in Switzerland of acreages being set aside in urban areas for subdivision into family garden plots could be adopted here. Even intelligent, part-time farming on the average suburban lot can supply a family with most of its own fruits and vegetables.

RG: Tell us about your farm and family, and how these ideals have played a role.

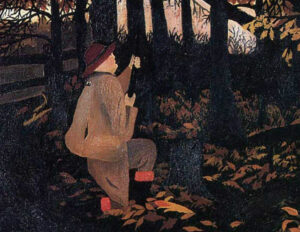

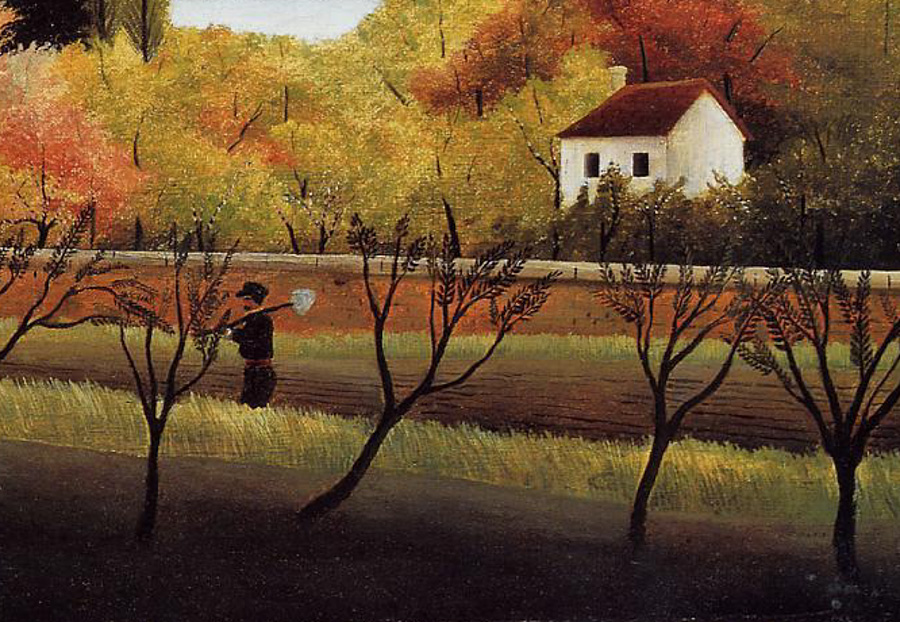

AC: Here at Swallow Farm, in Owen Township, Winnebago County, Illinois, we now practice what the Christian author Stephen Wood has labeled “grandfarming,” where we seek to use the farm to contribute to the physical, emotional, and spiritual formation of our grandchildren. At this point, they number nine, ranging in age from six months to nine years. We keep several goats and sheep, for lessons in the care and tending of four-footed farm creatures. We also raise chickens and ducks, primarily for their eggs. The grandchildren like nothing more than to take their turn at collecting and tending to the eggs each day, and there is no greater fun than catching and returning an errant hen to her appropriate chicken yard. (I take real satisfaction in delivering enormous, delicious, organic eggs to our dozen or so regular customers.) The grandchildren also help feed and water the turkeys that will grace our Thanksgiving and Christmas dinner tables each year.

The grandchildren like nothing more than to take their turn at collecting and tending to the eggs each day, and there is no greater fun than catching and returning an errant hen to her appropriate chicken yard.

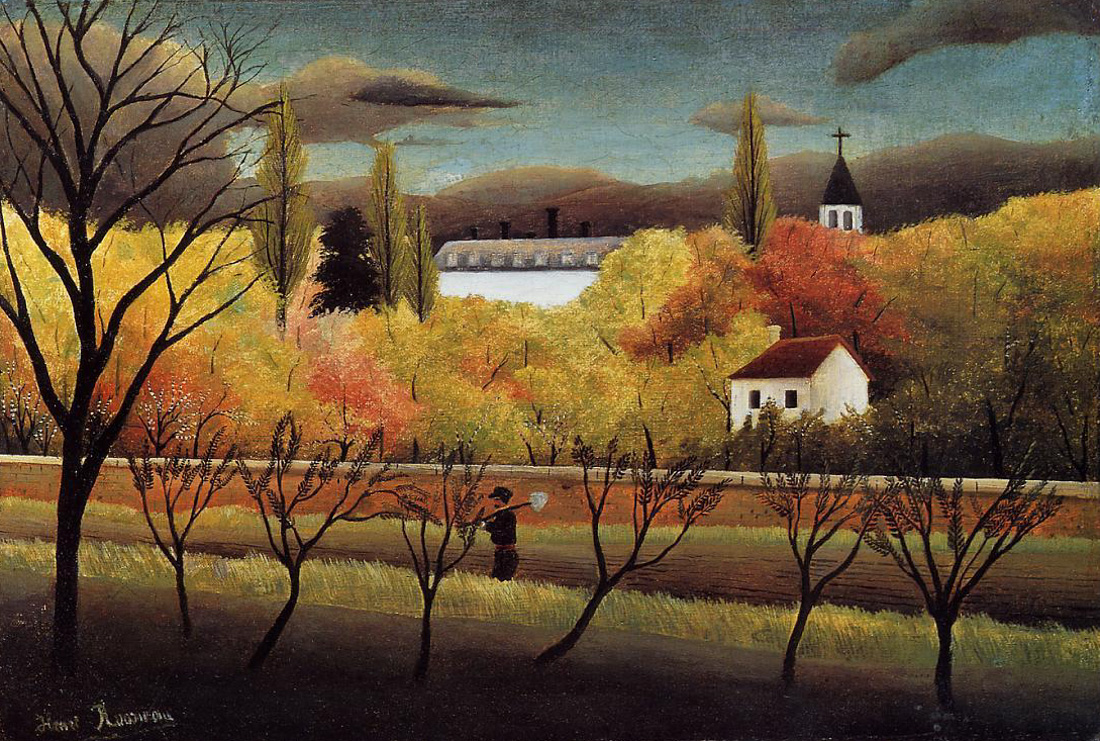

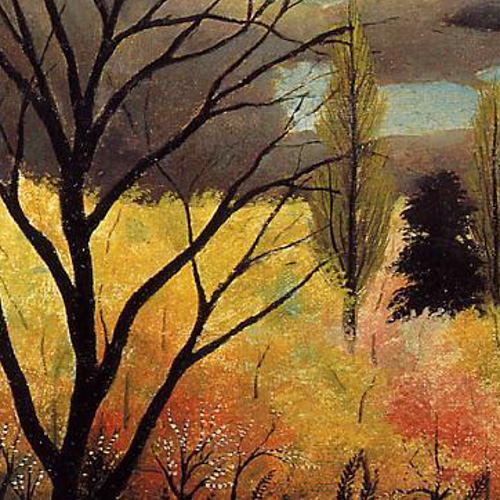

Our vegetable garden includes for family consumption and canning: yellow and purple beans; sweet corn; red potatoes; cucumbers; green peppers; and the like. We also sell commercially varieties of squash and tomatoes . . . caterers have become good customers for the latter. Swallow Farm also has twelve acres put into Midwestern prairie restoration. The flowers . . . are spectacular and a walk on the prairie path a delight. Beyond the prairie lie eighteen acres in woodland, including a fair number of walnut trees first planted by my father-in-law forty years ago and now spreading with the help of the squirrels. These have a good potential market value . . . most likely for our children and grandchildren.

RG: What is God speaking to you about most right now?

AC: In the midst of pandemic, economic crisis, violence, and the apparent breakdown of law and order, I turn again to some of the most basic questions: Why are we here? What is our purpose? How does God want us to live our lives? The Christian answer comes from Genesis 1 and 2, with elaborations from the Gospels and Epistles. And it points to “one flesh” marital unions and the begetting of children as pleasing to the Creator and the source of fulfillment and happiness for his creatures. Long human experience also shows how the family farm serves as an ideal “habitat” for the children co-created with God.

AC: In the midst of pandemic, economic crisis, violence, and the apparent breakdown of law and order, I turn again to some of the most basic questions: Why are we here? What is our purpose? How does God want us to live our lives? The Christian answer comes from Genesis 1 and 2, with elaborations from the Gospels and Epistles. And it points to “one flesh” marital unions and the begetting of children as pleasing to the Creator and the source of fulfillment and happiness for his creatures. Long human experience also shows how the family farm serves as an ideal “habitat” for the children co-created with God.

RG: You edited the book Land and Liberty: The Best of Free America. Why is it an important read for Americans today?

AC: This book shows the work of a band of Americans who sought to promote and build an agrarian/distributist order in the United States in the mid-20th Century. They favored a land of family farms, small shops, decentralized industry, and the freedom which the ownership of productive property begets. They also described themselves as “equally opposed” to fascism, communism, and finance capitalism. The wise English philosopher Sir Roger Scruton, who wrote the preface for this book shortly before his death . . . nicely summarizes their vision: “The real wealth of a country . . . does not reside in the hectic exchanges on the stock market or the rivers of commodities that flow through every household without belonging there. It resides in local communities, in the work that holds them together, and the deep investment represented by a home, a place and the endowment across generations of human love.” Such arguments ring with even greater clarity in our own time!