—Ink and Echoes—

Farmers

from

Vergil: Father of the West

Theodor Haecker

1935

Translated by Fr. Anthony Giambrone

The following is excerpted from Fr. Giambrone’s English translation of Vergil: Father of the West, published by Cluny Media.

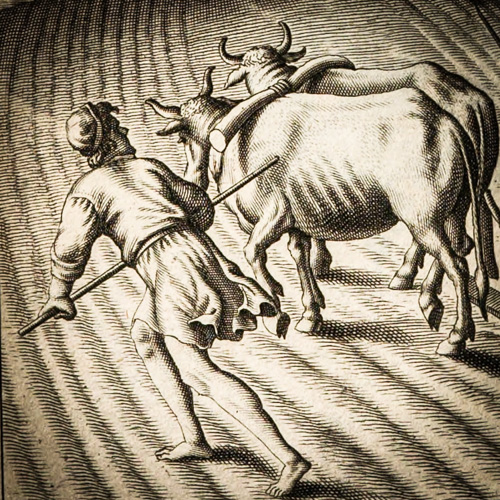

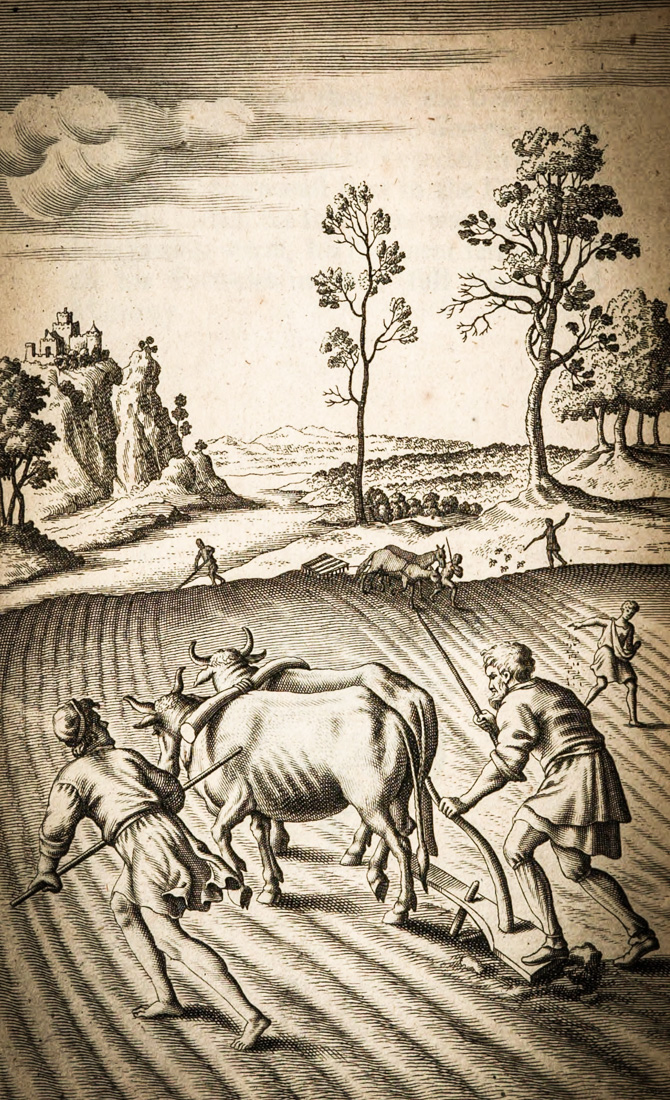

Who in antiquity could have written the sentence: Labor vincet omnia, labor improbus? Work conquers all, work by the sweat of the brow, in antiquity, in a slave economy, where every nobleman saw a noble thing only in otium and not in negotium, where no one so much as imagined the possibility of the modern aberration of holding work in itself to be a sort of religion. No Greek, no seafaring people, no merchant folk, no bandit tribe, no warring nation, no pastoral people, but only a people who worked the land could have come to the recognition of the essence of labor. An Italian farmer’s son, who up to the highest peak of sublime artistry, outdone by none, took with him his unwavering love for the humility of working the land, only he could write the most beautiful song of the earth, the Georgics, of working land and vine, of nursery gardening and animal breeding, of bees, the most revered and mysterious creatures in the literature of antiquity from Plato to Vergil.

This poem is truly no romantic, but the most classic of works one can imagine. It is a grotesque misunderstanding to wish to compare it to the sentimentality of Rousseau and Rousseau’s disciples, however much there was a justification for this movement: the right, namely, of fleeing from the lie of the Cartesian removal of nature’s soul. But the flight went off into a new lie. Vergil bound together in this his second work, the poet’s original love for nature, the intuitive knowledge of the land of a born farmer and all that is his, and the studied understanding of agriculture won through thoughtful observation and observant thought. His gift of observation is related to and comes near to that of the greatest naturalist of our age, the splendid Vergilian, J. H. Fabre.

This poem is truly no romantic, but the most classic of works one can imagine. It is a grotesque misunderstanding to wish to compare it to the sentimentality of Rousseau and Rousseau’s disciples, however much there was a justification for this movement: the right, namely, of fleeing from the lie of the Cartesian removal of nature’s soul. But the flight went off into a new lie. Vergil bound together in this his second work, the poet’s original love for nature, the intuitive knowledge of the land of a born farmer and all that is his, and the studied understanding of agriculture won through thoughtful observation and observant thought. His gift of observation is related to and comes near to that of the greatest naturalist of our age, the splendid Vergilian, J. H. Fabre.

Vergil bound together . . . the poet’s original love for nature, the intuitive knowledge of the land of a born farmer and all that is his, and the studied understanding of agriculture won through thoughtful observation and observant thought.

The first monks of the West had St. Benedict as their spiritual father, but as their worldly father, Vergil. They could very easily reckon Vergil’s Georgics as worthy of inclusion with the Holy Scriptures and their Rule. They went to the north, as sons of St. Benedict, in order to clear the primitive woods of wild souls and to cultivate their reception of the word; and they did this through their orare, their prayer. They went also as sons of Vergil, however, in order to clear the woods and the wild countries and to cultivate the land for the reception of grain and the vine; and they achieved it through their laborare, through work and by “the sweat of the brow,” the biblical expression that remains the best possible translation of the Vergilian labor improbus: they were Benedictines according to the order of grace, Vergilians according to the order of nature.  That alone should reveal the chasm separating Vergil and Rousseau, between the true beauty of the real and the pretty appearance of a romantic fiction. The son of a farmer and craftsman must say what the essence of meaningful labor is, for these two, the farmer and craftsman, provide the paradigm of meaningful labor, inasmuch as all other labor, even up to the most sublime work of the artist, judges itself against their worth. Work, the labor improbus, which for certain animals is already objectively present, nevertheless belongs entirely to man in consciousness and freedom; it stands in the middle, as a mediator, between the iustissima tellus, all-righteous Mother Earth, worked over by forced labor and the labor of love, the beginning, and the perfected fruit, nourishing and rejoicing the body, soul, and spirit of man.

That alone should reveal the chasm separating Vergil and Rousseau, between the true beauty of the real and the pretty appearance of a romantic fiction. The son of a farmer and craftsman must say what the essence of meaningful labor is, for these two, the farmer and craftsman, provide the paradigm of meaningful labor, inasmuch as all other labor, even up to the most sublime work of the artist, judges itself against their worth. Work, the labor improbus, which for certain animals is already objectively present, nevertheless belongs entirely to man in consciousness and freedom; it stands in the middle, as a mediator, between the iustissima tellus, all-righteous Mother Earth, worked over by forced labor and the labor of love, the beginning, and the perfected fruit, nourishing and rejoicing the body, soul, and spirit of man.

Culture, this word that today so moves and occupies the spirits of the entire West, comes not from the Greeks, who have otherwise gifted us with all catholic words; it is the gift of Latin famers and signifies the essence and art of working the land. Culture is the conception and inseparable unity of three things: of some given dead or animated stuff, which man does not create, but rather, much more, from which he himself is created, and of which he himself is a part; on top of this, the inescapable, imposed, mediating way of man’s formative labor improbus; and finally, through the inner connection of these two – of which the first has a grace-like, the second a work-like character – the perfected fruit and sustenance, rich in pleasure. But that is not all. To that must be added, for all true culture, the gloria, to which belongs the immediacy and also the absoluteness of beauty. Immediacy is only at the beginning and then again only at the end; lost is what sticks in the ordeal of the labor improbus. It is a long way from the immediacy of a folk song to the immediacy of a symphony of Beethoven, yet both possess it; and that the latter, bearing with it this unending richness of content, makes this richness transparent only though the labor improbus, and that it is never attained without it, is one of the most mysterious paradoxes of human life. Vergil would have been startled by the mediocracy of an aesthetic and poetic doctrine instructing poets to await passively the onset of inspiration and to live from it alone – by which many have indeed been shipwrecked. Admittedly, no labor, no sweat of the brow, replaces inspiration, as no farmer can make grain grow from stones; yet it receives it, already existing, and leads it to the goal of ripeness. Yes, it does still more; it attracts new things and multiplies their number; it does not create them, but labor leads them into the light through ease and dedication and readiness.

Admittedly, no labor, no sweat of the brow, replaces inspiration, as no farmer can make grain grow from stones; yet it receives it, already existing, and leads it to the goal of ripeness.

Beauty is there in the beginning and at the end. A wild cherry is beautiful and a wild vine. But what is that against the noble splendor of a full cherry, against the darkness of a grape? What is a spouting tare against an ocean of blond wheat, against the benevolence of an apple, against the sensuous feminine beauty of a pear, against the swelling blue cushion of a plum, against the childish cheek of a peach; what is it against the humble gloria of bread, of wine, of oil, of those sheer things that come only through culture, whose beginning is Eros, whose middle is the taming, guiding, steering work, and whose end is the lovely and spiritual sustenance of men and the gloria of the things themselves. That goes still farther and higher. A color is beautiful, but what is it against the gloria of one of Fra Angelico’s pictures? A sound is beautiful, but what is that against the gloria of one of Mozart’s sonatas? A ringing word is beautiful, but what is that against the gloria of Vergilian verse? The way from the one to the other, proceeding from the primordial given-ness of the colors, the sounds, and the speech with all their immanent relations and laws, which the painter, the musician and poet do not create, and of the creative, combining power and the access to this power that comes mainly from birth and in the native rights of the painter, musician, and poet, leads to the goal and to the fruit with the aid of the labor improbus. With all things, to attain with the most extreme toil the “toil-less,” with the most intrepid complexity the “simple,” this is the perfection of art, just as Kunst [“art”] comes from können [“to be able”]. That is one of the few absolute statements of an absolute aesthetic in its subjective aspect. And that is again real “imitation of nature” in the Aristotelian sense. The complexity of our most complicated machines is a shameful blunderbuss over against the complicated apparatuses and their functioning that nature creates. Is there anything more complicated, more dependent upon myriads and myriads of conditions than the apparatus and functioning of our eye? and on the other side: Is there anything more staggeringly and gracefully simple than: seeing? And here is the tremendous difference between nature and the machine: the achievement of the latter remains always, to the very end, in its complexity; never is its result the redeeming simplicity of a vital, much less of a spiritual act.

The normative greatness of Vergil’s Georgics, the book of agriculture and farmers, of labor and of the iustissima tellus, lies in this: that, with the surest vision, it discovers the meaning of work, a mighty problem of mankind, even one of the most tortured and confused in our times, there where its first native home is, by the farmer, in agriculture. In the company of the shepherds in the Bucolics it is first of all play, not yet work by the sweat of the brow, not yet labor improbus. Vergil neither overestimates nor underestimates the labor. The work itself creates nothing, for Mother Earth alone gives both the meager and poor, as well as the rich and full fruit. Yet, there is a difference, the difference of the labor, of the cultura in the narrow sense, between the wild and the cultivated grain. This one the tellus gives away freely; that one she gives away as iustissima, as righteous, just, only as the price of labor improbus. In every high and highest culture – a word carried over from agriculture – work, labor improbus, plays analogously the same role. It is the indispensable condition in order for an originally graced thing to become still more grace-filled, as the symphony of Beethoven is still more full of grace than a beautiful folk tune. The victory of real work proves itself through the victory of grace.

Theodor Haecker (1879 – 1945) was a German writer, translator, and Christian-humanist philosopher, whose voice was shaped during the tumultuous years between the two World Wars. He was openly opposed to National Socialism, leading the Nazi regime to attempt to silence him. He was forced to live under house arrest for the final decade of his life and prohibited from speaking or writing publicly. He continued, however, to write in secret. Haecker was a luminary during the darkest of times, and his work ought to be more widely known in the anglophone world.

Fr. Anthony Giambrone, OP, PhD, is a professor of New Testament at the École Biblique in Jerusalem. He is the author of many academic works and a frequent contributor to popular Christian publications. He is versed in various languages and is a noted translator of ancient and modern texts. He is the chaplain of Hearth & Field.