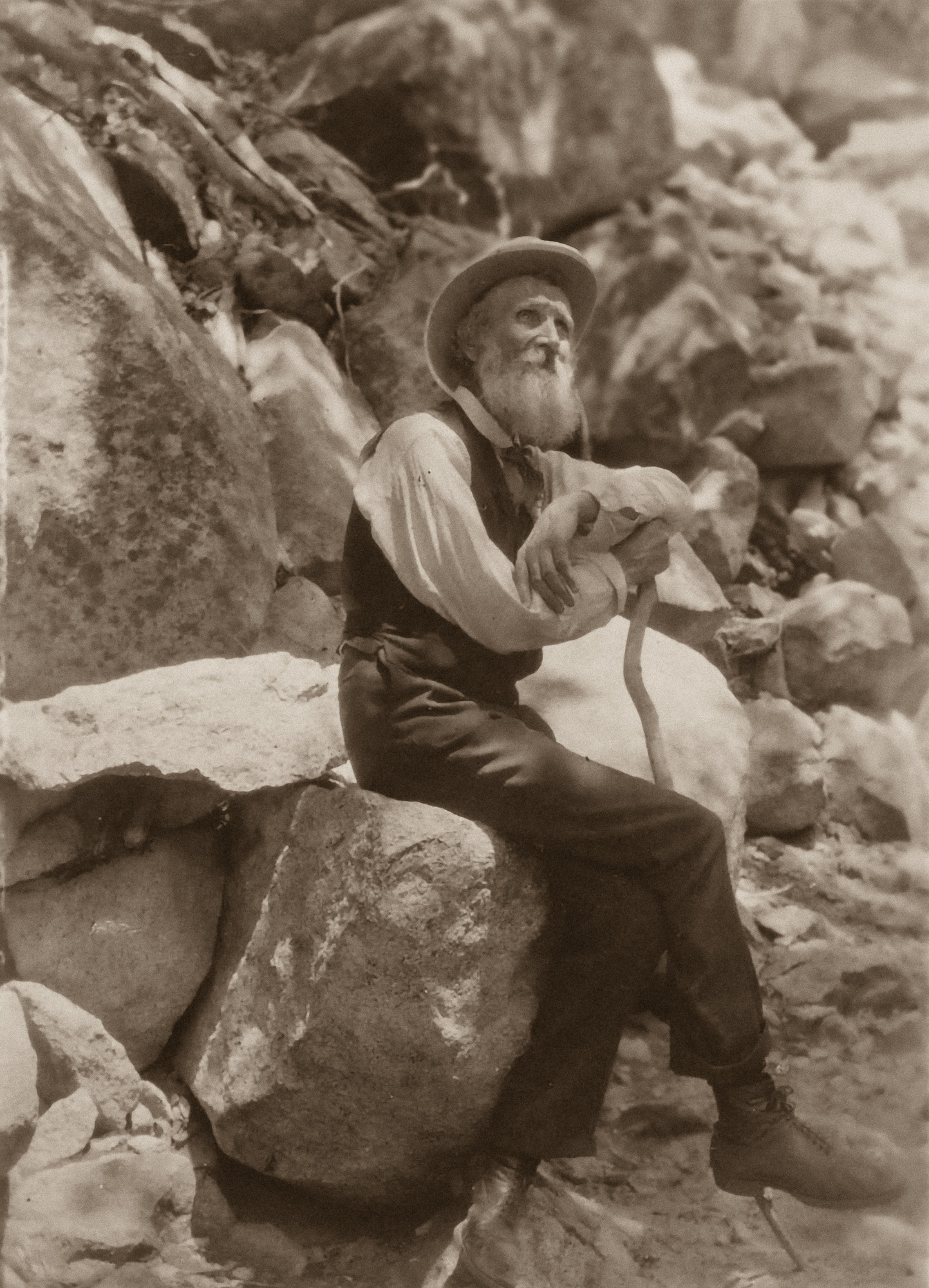

Being

John Muir

Dr. Jeff Gardner

In 1868, a dusty and tired John Muir arrived in San Francisco. He immediately asked someone for directions to get out of town. Muir’s intent, he said, was to go “anywhere that’s wild” and slip into the solitude of out-of-the-way places. Within three years, however, Muir found himself center-stage as a leading voice calling on the United States government to protect large tracks of its wildlands, and for every man, woman, and child to spend time in them.

John Muir was born in Scotland in 1838, but his family immigrated to the United States in 1849, and Muir’s formative years were spent in the wilds of Wisconsin. A pacifist at heart, Muir fled to Canada in 1863 to escape the draft of the Civil War. He returned to the States in 1866 and worked in a wagon wheel factory in Indianapolis, Indiana. While changing a belt on a lathe, Muir accidentally struck himself in the right eye, causing blindness in both for nearly six weeks. The accident was John Muir’s road-to-Damascus moment. After recovering his sight, Muir resolved to leave “this trivial world of men.” And thus Muir eventually found his way to Yosemite Valley and deep into the American environmental consciousness.Throughout his life, John Muir worked as an advocate for wilderness and the need to immerse ourselves in it.

Though Muir died in 1914, he lives on today — not only in the sense of grand legacy and collective memory, but in another, somewhat unexpected way as well. One man, Lee Stetson, has dedicated the last forty years to bringing John Muir back to life. Through a one-man show in which Stetson dresses, acts, and sounds like Muir, he is reconnecting people worldwide to Muir’s message, as well as the heart and soul of the great man. I recently had the pleasure of speaking with Mr. Stetson.

Unlike Muir, Stetson’s roots were eastern. He grew up in Maine, reading prodigiously as a child, and Thoreau was one of his first heroes — an attraction that led him to a Ph.D. program in American studies. But as part of his coursework, Stetson took a class titled, “American Theatre Before Eugene O’Neil,” which jolted him out of academics and into the theater.

Drawn to both the spoken and written word, Stetson began writing his own scripts and soon opened a theater company. The company was not financially successful, so Lee joined the Peace Corps, trained in Hawaii, and served in Southeast Asia. Returning to Hawaii, Stetson again began acting, but within ten years, through the 1960s and into the 1970s, he had “acted out” the roles that were available to him. Moving to Los Angeles for work, Lee found that he was overwhelmed by L.A.’s size, noise, and crowds.

“Having spent a lot of time in the wilderness of Hawaii,” Stetson told me, “I badly needed an escape from L.A. — so I began spending time on the John Muir Trail.”

Running two hundred and thirteen miles up the spine of the Sierra Nevada, the John Muir Trail stretches from Happy Isles in Yosemite Valley to the summit of Mount Whitney, the highest point in the lower, contiguous forty-eight states. “I was spending time hiking sections of the John Muir Trail,” Lee recalled, “when a friend gave me a copy of James Clarke’s ‘Life and Adventures of John Muir.’ I did not know much about Muir, but I was drawn to his character, his writing, his poetry, his talent, and his sense of wonder,” said Stetson.

Wonder indeed. Reading Muir’s accounts of his adventures, for example, how he climbed out on Fern Ledge under the twenty-four-hundred-foot-high Yosemite Falls, one marvels at Muir’s elation and near-complete lack of fear. Taking Muir at his word, we are left to wonder if he was brilliant, mad, or simply the ultimate wilderness tough guy (perhaps all of the above) — operating on a level that is far beyond most of us.

Returning to L.A., Stetson continued to struggle as an actor. In 1982, again needing a break from the city, he hitchhiked to Yosemite Valley. Arriving in the evening, Stetson settled at Camp Four and, feeling restless, hiked up to Columbia Point. As the moon rose over the valley, Stetson was transfixed and transformed.

“As soon as I saw Yosemite shining in the moonlight,” he recalled, “I knew that I needed to stay in that valley.”

The next morning, Stetson went straight to the Yosemite employment office and got a front desk job in the park. Over the next months, Stetson began to research and write a play. “My initial thought was to write a play that contained a number of characters of Yosemite Valley,” Stetson said, “since there was such a colorful list of them involved in the valley’s history.” But gradually, Stetson realized that the main character of the valley had been John Muir. By the end of 1982, Stetson reworked his initial idea for a play, transforming it into a one-man show featuring his portrayal of Muir.

“I presented the script to the Park Service,” Stetson recalls, “and pleasantly, they said, ‘Sure, let’s give it a go.’”

“I never imagined that the play would run for over forty years,” Stetson reflected. “Frankly, at the time, I was simply happy to have a production that was popular.”

Initially, Stetson’s portal of Muir was a role, a character that as an actor he simply ‘did.’ But not long after beginning his one-man show, first performed in a small theater in Yosemite Park, he realized that as he was shaping the role of John Muir, the role was shaping him. “I never imagined that playing John Muir would evolve into a life quest,” Stetson told me with genuine candor.

“After I started the play, within a short period of time, it became clear that it was larger than me, that there was a thirst for environmental enthusiasm, which erupted in the audience, and it very quickly became more than just another role that I worked as an actor,” Stetson said.

“There was something,” Stetson reflected, “that was unfolding on stage; it was much more than just a show.”

Soon, people worldwide began asking Stetson to come and portray Muir, including the famed documentarian Ken Burns. Stetson portrayed John Muir and did Muir’s voice for Burns’ 2009 award-winning documentary, “The National Parks: America’s Best Idea.”

But although Stetson has performed John Muir in prominent film and television appearances, he prefers the theater, or even better, small, intimate settings — sometimes as small as a campfire.

“The feedback is incredible,” he says. “In a way, I realize that in performing Muir, most times I am preaching to the saved, but this is vital; we need to hear and think about things in ways that we have not — that process of renewal is what keeps us going,” Stetson told me.

A product of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, John Muir was a preservationist, someone who fought to keep valleys such as Yosemite from falling under the pick and ax of those in search of raw materials to commoditize. Fast forward over one hundred years, and the United States is an age of conservation, not preservation. How does Stetson keep Muir’s message relevant to audiences?

“I don’t,” Stetson said flatly. “John Muir speaks for himself, and it is not necessary to split hairs between conservation and preservation.”

“I am certain of this,” Stetson reflected, “because the feedback from audiences has been, and remains, tremendous; it’s no stretch to say that it has kept me going for over forty years.”

All the applause while on stage aside, it is the feedback from individuals that has touched Stetson the most.

“I have stacks of letters from people all around the world who have told me that encountering John Muir in the show was a ‘transforming experience,’” Stetson said, emotionally. “Of course, I get emails, but I really do appreciate (and maybe even prefer) all the letters,” he said.

Of the many things that John Muir wanted to tell us, perhaps the most important was the need for us to encounter wild places. Both on and off the stage, Stetson is deeply moved that through his portrayal of Muir, people are still “heeding the call” of the mountains.

“Yes,” Stetson mused, “we need to encounter nature more, and we need to encounter each other more. John Muir understood both — he understood, on a deep level, that we were losing wild places and animals, and he understood that we need encounters with both. This is as true today as it was in Muir’s time.”

Perhaps, unsurprisingly, when not working or portraying John Muir to audiences of all sizes, Stetson can be found “anywhere that’s wild.”

“You know, getting out of L.A. and into the Yosemite Valley was the beginning of my journey. To continue that journey, I visit the National Parks, as many of them as I have time and energy to get to,” Stetson concluded.