Lizzie Magie & the Robot Barons

Monopolizing the Twenty-First Century

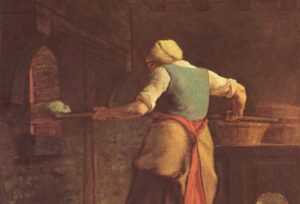

Mr. Samuel Butterofen

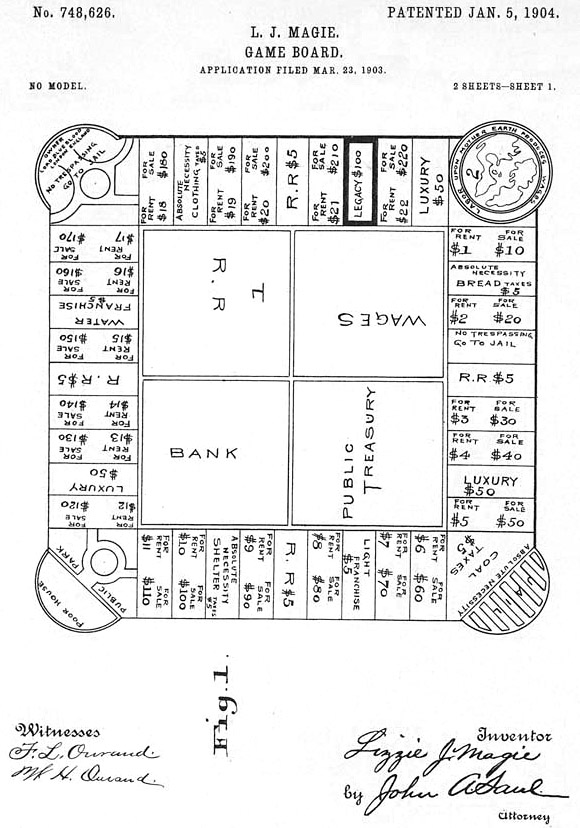

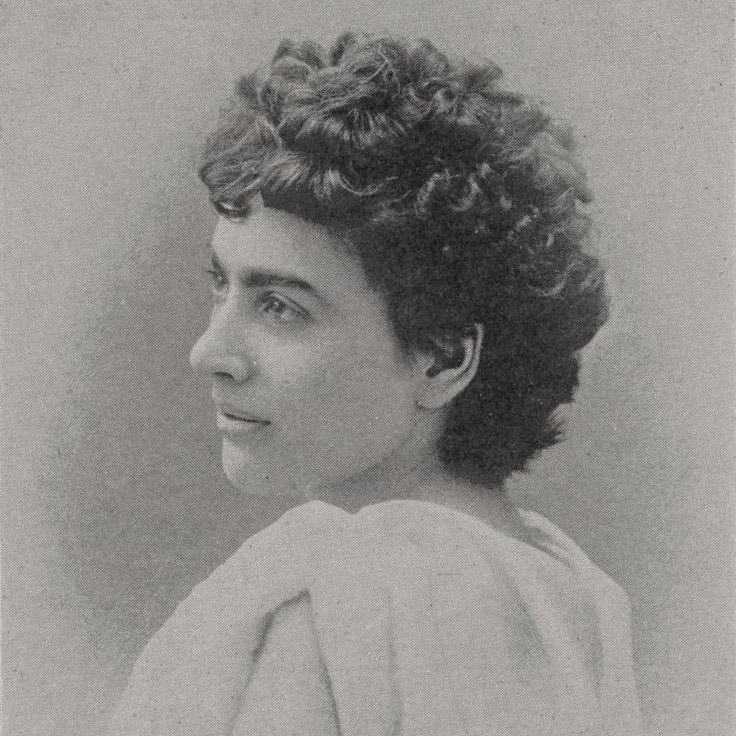

The memory of Miss Elizabeth Magie (1866-1948), writer, actress, engineer, abolitionist, first-wave feminist, American board game designer, and committed Georgist, has sadly fallen into oblivion behind the brand name of Parker Brothers. It was she, not the Parkers, who in 1903 invented Monopoly — or at least its precursor, in order to illustrate the tenets of her Georgist beliefs.

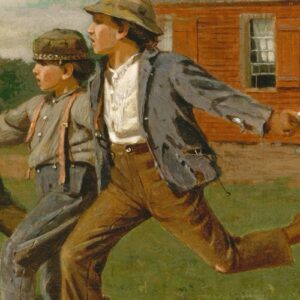

Georgism, named for Henry George, and largely forgotten like Magie herself, was a land-based, single-tax philosophy. Rooted in ideas reaching back to John Locke and Adam Smith, it held that people should own all the economic value they could create, while rent and resources derived from the land, i.e. a land-value tax, should be the sole source of funding for the government. The liberal tradition had, indeed, long recognized that public levy on land value is not subject to the same inefficiencies as other sorts of taxes. In the late nineteenth century, the target of this theory was clearly monopolies on resources such as iron and oil. These resources underwrote the prodigious growth of the Carnegies, Rockefellers, Vanderbilts, and their like: the so-called “Robber Barons,” monopolists who (at least in popular lore) ruthlessly ingested the wealth of the world.

George Swinnerton Parker, founder of the fraternal toy-making giant, and capitalist champion of homo ludens, proposed that, contrary to the reigning theory and social mores of the day, parlor games need not educate or advocate moral lessons. Miss Maggie, on the contrary, had something to say, and she found a clever and diverting way to say it: The Landlord Game. When Parker Brothers propagated the game, however, they left her lesson incomplete. In the original game, there were two sets of rules: one a Georgist anti-monopolist set, in which all were rewarded and common wealth was created, and one in which the goal was to get big and ever bigger and eventually crush everyone else. Her game had been a living-room-based laboratory for discovering, by experience, which system was better. There was, in short, an alternative to letting robber barons on Boardwalk and Park Place assert their inevitable, annihilating logic. Economics need not be played like the game of Risk.

There was, in short, an alternative to letting robber barons on Boardwalk and Park Place assert their inevitable, annihilating logic. Economics need not be played like the game of Risk.

Today, when the resources of a digital landscape have become the key field of tech-based “industry,” monopolies inevitably take on a different form. The seemingly endless resources of cyberspace create the easy illusion that no market share in this infinite world can be excessive or overly grabby. Setting up a virtual market place — an internet mall in the cloud — does not obviously deplete any limited resource. Likewise, each new virtual server added to the vast framework supporting all things digital is seemingly summoned out of nothingness with the click of a mouse. Such growth makes no overt run on natural resources such as iron or oil. So what could be the problem?

First, when our model tends ever more toward the consolidation of a “friendly” giant taking a private cut of the profits created by small manufacturing and small tech, it begins to look rather like a parallel system of tax: a para-state or mercenary mafia system, a menacing troll under the bridge, regulating a new feudal class of small shop owners and small technology entrepreneurs. We do not need a second, parallel tax system; the one we already bear is more than sufficient, thank you.

Second, even in a world of limitless resources, hyper-centralization of their control is inherently hazardous. As Mr. Nassim Nicholas Taleb has noted, the (highly stable) systems we find in nature do not tend to exhibit enormous disparities between parallel things. One man may grow to be twice as tall as another man, but he will never grow to be one million times as tall. Not so with manmade systems — consider the wealth distribution system at Amazon: Mr. Jeff Bezos’ net worth grew approximately fifty billion dollars over the past year, one million times the fifty-ish thousand dollar salary of an Amazon Prime truck driver. Similarly, the ever-expanding infrastructure undergirding the internet is dominated by a very small number of corporate leviathans. This is hyper-centralized capitalism at its extreme. As G.K. Chesterton rightly observed, “Too much capitalism does not mean too many capitalists, but too few capitalists.” And socialism would not alter the situation much, concentrating, as it does, wealth and power in the hands of the state (while spreading a thin layer like butter over the populace). The state-controlled technology concerns in China are proving an interesting study. Whether the hyper-centralization occurs in the politburo or in the boardroom, it remains hyper-centralization.

As G.K. Chesterton rightly observes, “Too much capitalism does not mean too many capitalists, but too few capitalists.”

Top-heavy architectures do not tend to maintain their balance. History is more or less a serial tale of their growth and collapse. Both phases are dangerous. As our modern, technocratic monopolists now begin to stretch themselves and explore the extent of their powers, we shall find out just how dangerous they may have already become. How much of mankind’s speech and enterprise will they be allowed to dictate? Time (and some upcoming court cases) will tell.

Third, and perhaps most concerning, is the fact that the appearance of limitless resources is, indeed, only the appearance thereof. A limiting factor is at play, which, even lacking a suitable, neo-Georgist board game, should incite us to cry together, “Stop!” What is this limiting factor, this exhaustible resource? The human person. How much of the earth’s labor force should one corporate entity — Amazon, let’s say — control? Surely the current numbers are staggering, if we consider the combination of direct employment, de facto authority over the aforementioned feudal class, and enmeshed relationships facilitating an invisible, overseas slave-labor force. An entity such as Amazon provides an uncanny service that may be faster and cheaper and fantastically efficient. But ever greater “customer satisfaction” as the exclusive measure of economic legitimacy and success is a dangerous metric. The human species is not only defined as a consumer. We are also homo faber. “Producer satisfaction” needs to have its place if our economic system is to be humane.

From our current vantage point, it appears things might get worse before they get better. The fifty-thousand-dollar Prime delivery driver may soon be replaced by a driverless truck and a flock of robot delivery drones. Mr. Bezos, Mr. Mark Zuckerberg, Mr. Sergey Brin, and the rest of the club have seen further than their nineteenth-century Robber Baron forebears. But our twenty-first-century monopolists stand on the shoulders of giants. We should pay both groups due homage by dubbing these new monopolists the Robot Barons.

In a twist of poetic injustice, Miss Magie and her game fell victim to the very forces she had hoped it might dispel. Through a series of questionable events, Parker Brothers acquired the game, and they themselves were ultimately amalgamated into the even larger Hasbro. In aggregate they have sold more than two-hundred-and-fifty million Monopoly boards over the past eighty-five years. The game currently retails for about $20. One billion people have played it. Miss Magie worked as a typist in her later years and died a widow with no children; her gravestone makes no mention of her creation. By most accounts, the compensation she received for the rights to the game was $500.

In her time as in our own, the robber and robot barons go about their endless machinations. We can expect no change to that. But the rest of us — the sane masses — must increasingly resist. We must oppose the hyper-centralized dehumanization of our economy, regardless of its ostensible convenience to businesses, buyers, monopolists, or certain government officials. The system distracts our work and endeavors from the ultimate sources of real human and land-based wealth and production (not to mention the ultimate Source of real human happiness). The tenets of Georgism, on their own, do not quite achieve the solutions we need. But given the monopolistic spiral in our economic affairs, and the continued failures of the two prevailing centralized economic systems, one may confess without shame the desire for third-way perspectives and creative means of expressing them. One hopes for a modern-day Lizzie Magie. One hopes that things will go better for her this time around.