Gentling

Gentling. I must admit, it took me a while to come to grips with the concept. I am sort of a “Peter” type, prone to jump out of boats without thinking, speak first and forcefully, and so on — I have managed thus far not to cut anyone’s ear off with a sword, but you get the idea. I spent my formative years working for farmers and later leapt headfirst into the shallow end of raising miniature cattle, but words such as patient, soft, and slow were never great descriptors of how I went about any of that. Then my wife got involved. Thank goodness she did.

As one of four boys growing up in a small, rural Missouri town, I was often volunteered for work on farms. Jobs were in ample supply for us: thistle removal, hog or cattle sorting and selling, working on hay crews, cleaning barn floors, and more. Time was of the essence, and we didn’t let the grass grow; the farmers I worked with needed things done and done yesterday! I won’t say they were harsh taskmasters, but there were urgent expectations of me when, let’s say, hogs or cows needed to be loaded for market or moved from one place to another. This did not always mean a gentle approach, or quiet or kind. I am not condemning the ways or the work, just observing what things were like, and what I was like, in my youth.

But now, as a husband and father, I am learning this concept and practice of gentling from my wife. She has a way of teaching me lessons that stick. It was her discovery of small farm life and livestock handling that brought gentling onto my radar. I only wish I would have learned its application much earlier in my life.

What is gentling? In simple terms, it is a way of interacting with livestock that focuses on gentle handling, through which an animal becomes docile. But that makes it sound too simple — as if you put batteries in the flashlight and poof! it turns on. The process of gentling takes time, experience, and most importantly patience to learn and then successfully apply. I am fortunate that my wife is the brains of our operation. She is the thinker; she gathers information instead of charging full steam ahead. To heck with the instructions; just get ‘er done — such was my motto. My wife is more sensible, and her entrance into farm life brought a wonder and an openness to learning.

Early on, she ran across the work of Temple Grandin, a professor at Colorado State University, who has overcome autism and more to become a leading expert in handling animals and designing facilities for them. Her work and talks are well-known, and her story has even become a movie. Grandin’s insight into the fight-or-flight response of livestock and the effects of stress and fear have vitally improved the welfare of the animals we farmers care for and depend upon. Take a short review of her work, and you will see a new approach for us Peter types. It shows that to decrease stress, fear, and the flight mechanism in an animal, a bond of trust — born of gentle handling — must first be established. Like us, an animal takes inventory of a situation and then identifies the course of action to take next. Remember, throughout history most animals were subject to predators and, instinctually, had to react quickly. That instinct is still intact.

Gentling proposes a new way of speaking to animals and moving around them. I again confess that my first introduction to animal handling and moving involved imposing my will on them and using a loud tone to get them to move quickly and go where I wanted. But now as an adult and husband and father, and as a student of gentling, I think of my children. Do I want them to do something primarily because they fear the consequences but then miss the process and learning involved? Or would I rather they understand the entirety of their actions and how to be accountable and responsible, able to make choices for themselves later? I would say the latter. Livestock cannot fully experience the deep sensibilities that children can, but they know the difference between motivation based on fear and motivation based on trust.

So where do you begin? Success lies in the observation of the “little things.” The patient observation of the animal leads to a greater understanding of her temperament. An investment of time in consideration of the details pays dividends in the gentling process. For example: develop a working knowledge of how sound and light play a role in creating a calm environment for the animal. Take into account how you will approach an animal, your position in relation to her sense organs, and the surrounding environment. Emphasis should be placed on not surprising or exciting an animal with loud noise or changes in light, which can cause the animal to feel threatened. Moreover, an assessment of your attitude toward the animal or herd will play a real role in the gentling process. Will you approach from a place of respect and care, or force and domination? This will feed directly into your approach as well as the influence of sensory perception. Two questions always to keep in mind: “How am I reducing stress for this animal?” and “Is the action to be performed one in which the animal is allowed to participate or is she forcefully controlled?”

Here are a few things I have learned in this process. Breathe first! Patience is an essential virtue (which I often held in short supply but am learning so powerfully now): patiently and slowly, quietly and gently speak and move around an animal you are first coming to know. And take the time to study the breed of animal you are going to work with. How invested are you in getting to know both the breed and the particular animal you hope to construct this bond of trust with? It requires time and effort.

We must recognize, for example, the importance of understanding how an animal’s eyes work and where they are located. How does your animal use her senses of sight to process you and the environment? I know that my little Herefords’ eyes are located on the sides of their head, so they see in a different manner than I do. I work to stay to the side of them so they can see me and know I am there. If I approach briskly and loudly from the front or the back, it will scare them, and then they will run.

Cows will move with us if allowed to see their options in front of them and a clear, non-threatening path ahead. We must reveal to them an avenue that is inviting and one they can voluntarily move towards with curiosity, not fear. By remaining in eyesight and to their back flanks, at a distance not directly beside them, they will move readily in the direction that lies in front. If they are unable to keep eye contact with you, if they cannot discern the path to safely travel, they will “spook”; the flight instinct kicks in and they will scatter. You will see them retreat to a place they feel secure, from which they can see you clearly. But when we are gingerly and slowly walking and remaining out of their blind spot, our Herefords move easily.

Sound is another key to gentling. I watch to see our cows’ or donkeys’ ears turn to hear my footsteps approaching, and then I move slowly into their sight lines from the side, making them aware that I am there and that I am not rushing in to harm them. I consider the tone of my voice in how I speak to them or to other people who are with me. Soft tones and a slow gentle inflection help avoid bringing unwanted noise and stress to the situation.

And don’t forget basic science: sound waves travel through and around visual obstacles, so your animals hear you before you may even see them. If I clang gates or chains or yell for the dog to go back to the house, our animals are already assessing the situation, and I may need to reset the environment, restoring quietness, before ever entering the pasture or corral with them. It sounds insignificant, but the quieter and calmer you are as you approach, the better they will receive you upon coming into their home.

We must also consider animals’ stature and size. An animal may be threatened and aware of our posture and stance. As with engaging children, we at times must safely approach an animal’s level. Larger animals may simply need to see that our posture is not one of rushing, roughness, or aggression. How do you picture yourself as gentle? Manifest that.

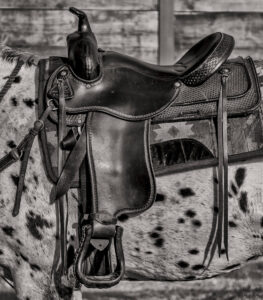

With time and soft, patient efforts, with appropriate attention to these matters of visibility and sound (and some good food), an animal allows us to get close to her. It is then time to allow her to feel what our touch is like. I cannot emphasize enough: being gentle in touch is needed for this to be successful. I grew up roughhousing our dogs and wrestling my brothers. I was used to slapping or patting dogs, or brothers, on the side and loving them that way. But cows, donkeys, and many other animals do not like this kind of touch! They prefer a slow-moving hand and fingers upon them with steady, light pressure letting them know you are there, not a sporadic show of affection that spooks them into stress or jumpiness. For example, those familiar with horses or donkeys understand the work it takes to build that bond of trust so you can pick their hooves. Softly interacting with them and letting them become familiar with your hand moving carefully and slowly on their legs and hooves builds trust. I create a bond that allows our little donkey to now let me lift its hoof and pick it clean. Also, get to know the places a particular animal likes touch and won’t avoid contact. Important, as always, is how they are able to see you. Are you impeding their movement so they feel trapped or threatened? If so, getting close enough to touch them might be impossible — or possibly might get you kicked.

Far better, and safer, is the gentle approach. It is a lesson in learning, observation, and patience. And journeying with an animal from beginning to end is powerful. It leads to internal growth and a deepening of our understanding not only of animals but of ourselves. Strength lies in our willingness to invest in time, study, and experience. Temple Grandin is a great next step if you are new to the concept.

It’s a hard lesson for those like me who want things done yesterday. But it has changed our farm. And once my eyes were opened to the way our animals respond, it changed my life! I can feel the gaze of the Lord guiding me to see its application beyond that of my herd. It is a bond of love and trust that can be built gently and patiently over time. Once this trust is established, growth can take place. Managing animals — or humans — from a place of frustration or angst or impatience or hurry (. . . the list goes on and on) builds only relationships of fear. And fear clouds wisdom. Making an investment of time into a relationship with a creature and allowing her to get to know and trust you will reveal something deeper in you. You will recognize your own growth in virtue and understanding. The “handler” now is not handling: he is walking with the beautiful creature gifted to him.