God Left the Garden Incomplete

A brief History of Judeo-Christian Relationship with the Land

Dr. Ryan Hanning

As a professor and researcher, I study the history of ideas, their development, significance, and permanence, or their brevity as the case may be. As a devout Christian, I seek to live my faith in relationship to the world around me. This includes not only the vertical, upward relationship towards God, and the horizontal relationship with others, but also the vertical downward relationship with the land. After all, the land plays a central role in the history, theology, and liturgy of both Judaism and Christianity. Provided here is a succinct historical overview of the central ideas of the land, ecology, care for the environment, and stewardship that underlie the Judeo-Christian tradition. I use the term Judeo-Christian very specifically here not to equate nor diminish the distinctive contributions of each on the subject of ecology — nor to suggest that there is one ecology shared by them — but rather to draw attention to the shared system of values regarding the environment that flows from Judaism into Christianity. Considering this history, we can examine what is unique and promising, as well as what is common and challenging to the ecological concerns of our age.

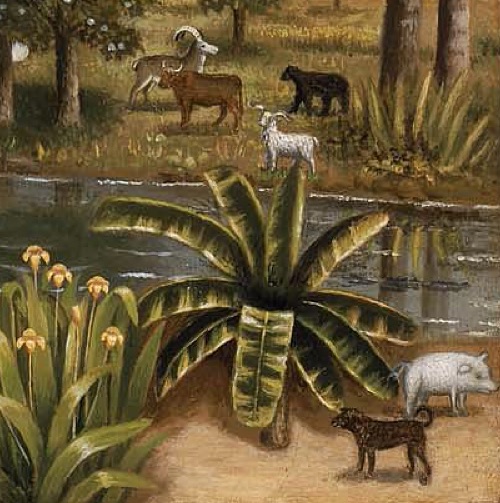

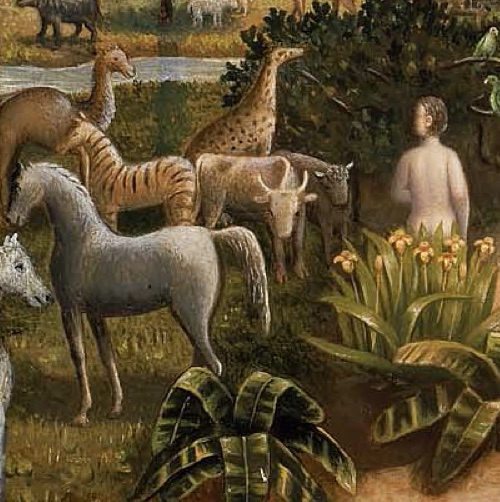

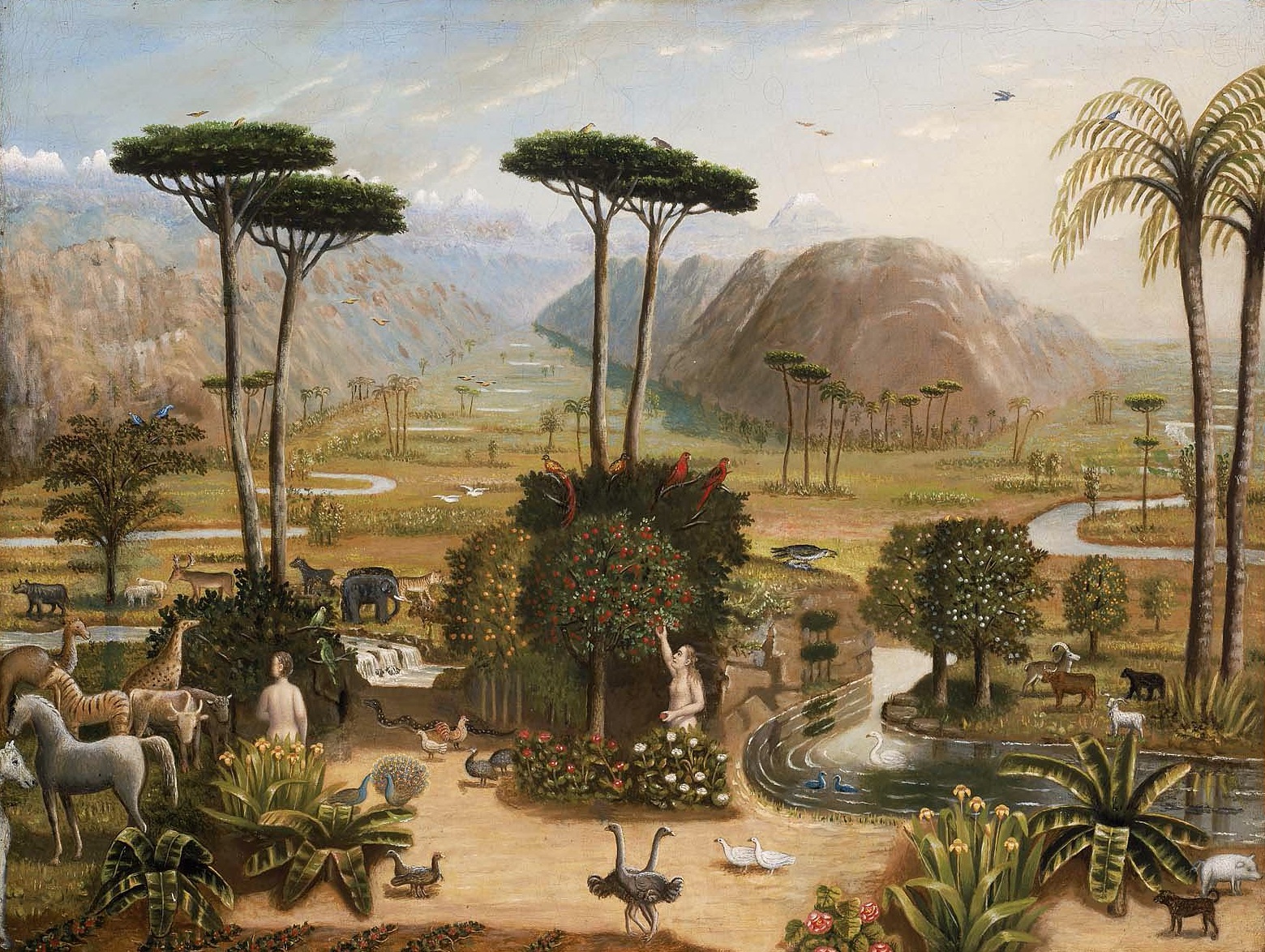

The title of this essay invokes the aphorism of Rabbi Akiva, who in the First Century A.D. reflected on man’s participation in the garden saying, “both world and man were created incomplete, God having left to man to perfect both his environment and his body.” In the beginning, God created the world. This personal and self-revelatory act from an all-powerful God provides a narrative in which to understand who God is and how mankind ought to relate to him. In the first chapters of Genesis, God presents himself as imminent, yet transcendent to his creation, and omnipotent, yet prudent in how he creates. God places himself in relationship with his creation and has made man in his image and likeness; we, in a particular way, are capable of being in relationship with God (Gen 1:26). Prior to the Fall, we can see that we are made to be in right relationship with God, with each other, and with the land.

This three-part relationship transects the vertical and horizontal lines of human existence. We leave the first chapter of Genesis with the commandment to be “fruitful and multiply” and also to “have dominion over all the earth”. In the second chapter, we are told this “dominion” will be both to “guard and till” the soil (Gen 2:15). Jews and Christians share a similar ecological reading of Genesis 1 and 2. God creates autonomously, out of nothing, independent of any necessity. God creates in an orderly and progressive manner, discernable by his creation (cf. Romans 1:20). God creates man and women in his image and likeness, interdependent on him, on one another, and on the land. Ultimately, he calls man to share in the care, cultivation, and sanctification of his creation. Adam and Eve are co-workers, stewards, and priests. A deep ecological ethos underlies both the moral and liturgical imagination of Judaism and Christianity. However, the ecological reading of the rest of Genesis is confronted by divergent interpretations of the Fall, and its consequences on humanity and the rest of the natural world.

This three-part relationship transects the vertical and horizontal lines of human existence. We leave the first chapter of Genesis with the commandment to be “fruitful and multiply” and also to “have dominion over all the earth”. In the second chapter, we are told this “dominion” will be both to “guard and till” the soil (Gen 2:15). Jews and Christians share a similar ecological reading of Genesis 1 and 2. God creates autonomously, out of nothing, independent of any necessity. God creates in an orderly and progressive manner, discernable by his creation (cf. Romans 1:20). God creates man and women in his image and likeness, interdependent on him, on one another, and on the land. Ultimately, he calls man to share in the care, cultivation, and sanctification of his creation. Adam and Eve are co-workers, stewards, and priests. A deep ecological ethos underlies both the moral and liturgical imagination of Judaism and Christianity. However, the ecological reading of the rest of Genesis is confronted by divergent interpretations of the Fall, and its consequences on humanity and the rest of the natural world.

Adam and Eve are co-workers, stewards, and priests. A deep ecological ethos underlies both the moral and liturgical imagination of Judaism and Christianity.

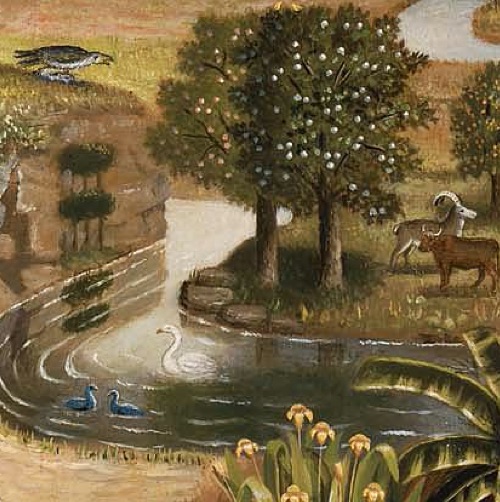

In Judaism, the basic ecological reading of Genesis continues through Abraham and the patriarchs. God has revealed to his chosen people how to reestablish the relationships strained by the Fall. The instructions of right worship include a variety of rules and laws that establish a participative and sacred relationship with the land. Here, the land is both the promised sacred inheritance of the Jewish people and the entire natural world on which our survival depends; both a particular inheritance (for the chosen people) and a general inheritance (for all people). Within early Judaism, we can see this connection between the land (both general and particular) and right worship. This connection is present in the sacrificial practices of Abraham, as well as the kosher and agricultural regulations of Exodus and Leviticus. This is also seen in a remarkable way in the Mishnah—the oral tradition of Jewish law—which includes a significant piece of theological and practical wisdom in its book on Zera’im (Seeds).  The entire first section of the Mishnah is dedicated to agriculture and begins with how the fruits of the land connect to proper worship, followed by how our interaction with the land relates to the care of our brothers and sisters. This ecological priority fills much of Jewish thought. The Avot of Rabbi Natan admonishes the faithful “if you have a plant in your hand and they tell you the Messiah is coming, first plant and then go and welcome the Messiah.” From within a particular ecological viewpoint, all of Jewish liturgy has this reminder and call to a participative ethos in how we approach the land. Rabbi Sacks, author, theologian, and former Chief Rabbi in the UK illustrates this point in his reflection on the Sabbath. “The earth is not ours but God’s. For six days it is handed over to us, but on the seventh we symbolically abdicate that power. We may perform no ‘work,’ which is to say, an act that alters the state of something for human purposes. The Sabbath is a weekly reminder of the integrity of nature and the boundaries of human striving.”

The entire first section of the Mishnah is dedicated to agriculture and begins with how the fruits of the land connect to proper worship, followed by how our interaction with the land relates to the care of our brothers and sisters. This ecological priority fills much of Jewish thought. The Avot of Rabbi Natan admonishes the faithful “if you have a plant in your hand and they tell you the Messiah is coming, first plant and then go and welcome the Messiah.” From within a particular ecological viewpoint, all of Jewish liturgy has this reminder and call to a participative ethos in how we approach the land. Rabbi Sacks, author, theologian, and former Chief Rabbi in the UK illustrates this point in his reflection on the Sabbath. “The earth is not ours but God’s. For six days it is handed over to us, but on the seventh we symbolically abdicate that power. We may perform no ‘work,’ which is to say, an act that alters the state of something for human purposes. The Sabbath is a weekly reminder of the integrity of nature and the boundaries of human striving.”

The Talmud and other Jewish writings tend towards a unified theology of the environment. While there are wide discussions and diverse views on the particulars, the essential beliefs that we are fashioned as co-creators in the Garden and that we cannot be in right relationship with God without upholding the dignity of the land and participating with it well, are generally maintained throughout Jewish ecology.

A basic and unified Christian ecology is more difficult to speak of. This is not because Jesus lacked a clear ecological vision. In addition to affirming the basic Jewish understanding of creation, Jesus also advanced a deeply agricultural ethos directly connected to his social and spiritual teachings. Within the first thousand years of Christianity, you have a consensus among the Church Fathers. Creation is sacred and it reveals something about the nature and character of God and our mission in the world.

This vision, of course, was inherited both from Judaism and from the Hellenistic culture that while more dualistic, still inscribed the divine within the natural world. At various times, often in reaction to pagan beliefs, the Church either elevated the goodness of the material world or downplayed its goodness in fear that it may be worshipped. One can think of St. Augustine’s fierce rejection of the Manicheist view that all matter was evil, or St. Boniface’s felling of a tree worshiped by the Germanic tribes. St. Francis of Assisi, in many ways, woke the Church in the west out of what could have become a hostile view of nature. Francis’ filial relation to the material world was a lived Christian expression of Jesus’ ministry of reconciliation, not only between mankind and God but between mankind and creation.

Francis’ filial relation to the material world was a lived Christian expression of Jesus’ ministry of reconciliation, not only between mankind and God but between mankind and creation.

Despite the difficulty in speaking of an essential Christian ecology, the three-part schema of relationships persisted. The high medieval theologies of both Aquinas and Bonaventure support the essential relational and instructive role of nature. Aquinas argues that creation is good, and Bonaventure reminds us that “we are created [such] that the material universe itself is a ladder by which we may ascend to God.” Martin Luther, whose vision of man’s depravity helped propel the protestant reformation, saw man’s corrupted agency as the problem, not his material nature. He echoes very much the same vision of the goodness of creation saying that “divine essence can be in all creatures collectively and in each one individually more profoundly, more intimately, more present that the creature is in itself…it encompasses all things and dwells in all.”

The continued fragmentation of the Christian faith in the 16th century introduced new ideas, many of which saw nature in the post-fall world as either inert or as hostile and irredeemable by the efforts of man. Calvin developed a more distinctive post-fall relationship with the land that differed from both Catholic and Lutheran beliefs. These views, along with the new enlightenment philosophies that saw the natural world as less a gift to be received, and more a code to be cracked or a problem to be solved, further divided Christian ecology. Within the past five hundred years of divided Christendom, you could find the sister errors of abdicating our role as co-creators in the garden and distorting our role to the point of dominating the natural world. Both errors contradict the participative ethos generally found in Judaism and early Christianity. This oversimplified and brief snapshot illustrates that it is difficult to speak of a historically unified Christian ecology.

It was not until the more recent questions of modernity and the advent of the industrial revolution that a clearer sensibility of stewardship within Christianity was developed. A sensibility that connects our worship of God with a priority of right relationship with the land. We see this first in the moral imagination of Christian authors who wrote extensively about the ills of over-consumption and disregard for nature of the 19th and 20th centuries. JRR Tolkien’s The Hobbit and Lord of the Rings, as well as CS Lewis’s Chronicles of Narnia, contain themes essential to rediscovering a more Christian ethos of ecology. The influential British authors G.K. Chesterton and Hilaire Belloc, among others, provided criticism as well as proposed reforms for a more humane relationship with the natural world. During the same time, doctrines of various Christian communities regarding our relationship with the land, and that relationship’s impact on our moral obligations to others converged into a much more unified whole. In the past fifteen years, there has been a proliferation of content on the subject. As a historian and theologian, I find this moment to have the rare features of a simultaneous systematic doctrinal response along with a growing moral imagination on the subject.

It was not until the more recent questions of modernity and the advent of the industrial revolution that a clearer sensibility of stewardship within Christianity was developed. A sensibility that connects our worship of God with a priority of right relationship with the land. We see this first in the moral imagination of Christian authors who wrote extensively about the ills of over-consumption and disregard for nature of the 19th and 20th centuries. JRR Tolkien’s The Hobbit and Lord of the Rings, as well as CS Lewis’s Chronicles of Narnia, contain themes essential to rediscovering a more Christian ethos of ecology. The influential British authors G.K. Chesterton and Hilaire Belloc, among others, provided criticism as well as proposed reforms for a more humane relationship with the natural world. During the same time, doctrines of various Christian communities regarding our relationship with the land, and that relationship’s impact on our moral obligations to others converged into a much more unified whole. In the past fifteen years, there has been a proliferation of content on the subject. As a historian and theologian, I find this moment to have the rare features of a simultaneous systematic doctrinal response along with a growing moral imagination on the subject.

As a historian and theologian, I find this moment to have the rare features of a simultaneous systematic doctrinal response along with a growing moral imagination on the subject.

It would suffice to give just a sample of the recent documents from the world’s Christian churches to illustrate this point. Nearly every denomination has provided a specific and concise doctrinal statement on their traditions’ vision of Christian ecology and their intended approach to the stewardship of creation. [See Appendix following this essay.] The referenced statements provide an overwhelming unified Christian response to many of the environmental challenges we face. They collectively provide a Christian ecology that is rooted in a shared theology and history that refreshingly transcends division and denomination. In addition, these documents call us to a more serious, more intentional, deeply Christian participative and reciprocal relationship with the land that God has given us. What Wendell Berry, the great Christian agrarian, calls “kindly use.” Unfortunately, this renewed doctrinal awareness and articulation continues to lack a clear pastoral response in which to form and animate the faithful. Perhaps this is why so many individuals, on their own, are responding in new, bold, and collective ways to integrate their faith convictions with a more agrarian ethos. And to my mind, this is a good thing. The laity need not a mandate nor permission to reclaim and rediscover the heritage to which they belong.

History tells us that the elevation of Christian conscience has never been a top-down proposition. The renewal of a Christian agrarian ethos that prioritizes stewardship and right relationship with the land will not be the result of a church decree or even less so the result of a solitary political solution. Rather, it will be our own individual personal and collective conversion and rediscovery of a deep ecological consciousness that is guided by our Christian faith, which will incarnate and make possible what polity will later advance and protect. A vision of right relationship with the land that is as beautiful and good, as it is true and concrete. A vision that connects our relationship with God precisely to how we treat others and treat the common home he has gifted to us and called us to care for. A vision that sees the natural world as a wonderful and necessary part of our preparation for the next world. A vision that marries the imminent realities of this world, and how they connect to our eternal destiny. So, all this begs the question, what is next? I do not presume that there is a simple answer, but I sense that the Holy Spirit is already at work and that a new unified Christian response to the challenges we face is not only possible but is surprisingly present.

History tells us that the elevation of Christian conscience has never been a top-down proposition. The renewal of a Christian agrarian ethos that prioritizes stewardship and right relationship with the land will not be the result of a church decree or even less so the result of a solitary political solution. Rather, it will be our own individual personal and collective conversion and rediscovery of a deep ecological consciousness that is guided by our Christian faith, which will incarnate and make possible what polity will later advance and protect. A vision of right relationship with the land that is as beautiful and good, as it is true and concrete. A vision that connects our relationship with God precisely to how we treat others and treat the common home he has gifted to us and called us to care for. A vision that sees the natural world as a wonderful and necessary part of our preparation for the next world. A vision that marries the imminent realities of this world, and how they connect to our eternal destiny. So, all this begs the question, what is next? I do not presume that there is a simple answer, but I sense that the Holy Spirit is already at work and that a new unified Christian response to the challenges we face is not only possible but is surprisingly present.

Nearly seventy-one percent of US citizens claim to be Christian and as many as sixty-two percent indicate that they belong to and attend a particular church. Over two hundred million Christians in our respective churches would be an incredible force for reclaiming a more humane vision of our relationship with the land. We have much to learn from our own tradition, and much to contribute to a fruitful, faithful, and truly humane dialogue about caring for creation without forgetting our transcendent end. Now is the time for Christians to bring their faith, their heritage, and their deepest held convictions to contribute to the work of all people of goodwill who are seeking a new model for being in relationship with the land. A new model which, as often is the case, is dependent upon a rediscovery and renewed appreciation of the old.

Author’s note: This essay was based on a paper I gave at the Conference on Faith and Science hosted at Arizona State University in 2019. As the only non-scientist invited to give a talk and lead a panel I was heartened and intrigued by how their research and examination of the natural world inspired and directed by their personal faith led to such similar conclusions about the value, beauty, and goodness of the land.

Annotated Appendix of Statements on the Land

Greek Orthodox: Archpatriarch Dimitrios, the previous Oecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople and visible head of 260 million Orthodox Christians, connected the Church Fathers to the consistent call of Christians to be in right relationship with all of creation. In 1989, he declared Sept 1st (Feast of Indication, Orthodox New Liturgical Year) as a Day of Protection of the Environment. Saying, “the Orthodox Church, watches with great anxiety the merciless trampling down and destruction of the natural environment which is caused by human beings, with extremely dangerous consequences for the very survival of the natural world created by God.”

“…In view of this situation the Church of Christ cannot remain unmoved. It constitutes a fundamental dogma of her faith that the world was created by God the Father, who is confessed in the Creed to be ‘maker of heaven and earth and of all things visible and invisible.’ According to the great Fathers of the Church, Man is the prince of creation, endowed with the privilege of freedom. Being partaker simultaneously of the material and the spiritual world, he was created in order to refer back creation to the Creator, in order that the world may be saved from decay and death.”

His successor, Archpatriarch Bartholomew, has used the “Day of Protection of the Environment” to provide detailed catechesis on stewardship, care for creation, and human development. In 2018, he called “for theology to showcase the environmentally-friendly principles of Christian anthropology and cosmology as well as to promote the truth that no vision for humanity’s journey through history has any value if it does not also include the expectation of a world that functions as a real “home” (oikos) for humanity.”

Episcopalian: Providing one of the earliest cohesive responses they adopted the “Resolution on Environmental Responsibility” at the 70th General Convention in 1990. Declaring “that Christian Stewardship of God’s created environment, in harmony with our respect for human dignity, requires response from the Church of the highest urgency; Calls on all citizens of the world, and Episcopalians in particular, to live their lives as good stewards with responsible concern for the sustainability of the environment and with appreciation for the global interdependence of human life and the natural worlds.

Presbyterian: In 1990 they issued their “Restoring Creation for Ecology and Justice”. It appealed to its faithful and all believers that “God’s works in creation are too wonderful, too ancient, too beautiful, too good to be desecrated.”

Roman Catholic: Pope Benedict XVI wrote a significant collection of works on ecology and worked to advance “green initiatives” throughout the building and development programs of the Catholic Church. His World Day of Peace Address’ focused on the environment as “that covenant between human beings and the environment, which should mirror the creative love of God, from whom we come and towards whom we are journeying.” He used the occasion of 2010 to issue a message titled “If you want peace, protect creation” and his subsequent encyclical Caritas in Vertitate further developed the theme.

Pope Francis issued the most complete treatment of the subject in his 2015 encyclical Laudato Si: On Care for our Common Home clearly connecting Catholic social teaching and integral human development to the care of the environment. He provided a broad sweeping theological examination of the human relationship with the natural world. “Human life is grounded in three fundamental and closely intertwined relationships: with God, with our neighbour and with the earth itself. According to the Bible, these three vital relationships have been broken, both outwardly and within us. This rupture is sin. The harmony between the Creator, humanity and creation as a whole was disrupted by our presuming to take the place of God and refusing to acknowledge our creaturely limitations. This in turn distorted our mandate to “have dominion” over the earth (cf. Gen 1:28), to “till it and keep it” (Gen 2:15). As a result, the originally harmonious relationship between human beings and nature became conflictual (cf. Gen 3:17-19).”

Pope Francis and Bartholomew I issued a more recent Joint Statement on Sept 1st, 2017, providing an even greater urgency to their concerns.

“Our propensity to interrupt the world’s delicate and balanced ecosystems, our insatiable desire to manipulate and control the planet’s limited resources, and our greed for limitless profit in markets – all these have alienated us from the original purpose of creation. We no longer respect nature as a shared gift; instead, we regard it as a private possession. We no longer associate with nature in order to sustain it; instead, we lord over it to support our own constructs.

The consequences of this alternative worldview are tragic and lasting. The human environment and the natural environment are deteriorating together, and this deterioration of the planet weighs upon the most vulnerable of its people. The impact of climate change affects, first and foremost, those who live in poverty in every corner of the globe. Our obligation to use the earth’s goods responsibly implies the recognition of and respect for all people and all living creatures. The urgent call and challenge to care for creation are an invitation for all of humanity to work towards sustainable and integral development.”

American Baptist: The American Baptist Association of Churches issued a letter in 2012 titled “Our Only Home” which catalogs the abuses and provides specific scientific details to the current state of the environment. “We believe that ecology and justice, stewardship of creation, and redemption are interdependent.”

Anglican: Forming the Anglican Communion Environmental Network, they provide resources and support to several initiatives outlined in The World is our Host: A Call to Urgent Action for Climate Justice. “At this time of unprecedented climate crisis, we call all our brothers and sisters in the Anglican Communion to join us in prayer and in pastoral, priestly and prophetic action. We call with humility, but with urgent determination enlivened by our faith in God who is Creator and Redeemer.”

Evangelical: Recently a group of Evangelical Churches under the auspices of the Evangelical Network Environmental developed the Evangelical Declaration on Care of Creation, stating “humans, created in the image of God, are called to care for creation, and to seek ways of living out these principles in our personal lives, our churches, and society.” In 2015, the National Association of Evangelicals in America issued A Call to Action and officially adopted resolutions and built upon a statement from 1970, calling “those who thoughtlessly destroy a God-ordained balance of nature are guilty of sin against God’s creation.”

Evangelical Lutheran: Their statement Caring for Creation: Vision, Hope and Justice draws a direct spiritual connection between degradation of the earth and degradation of humanity. “We know care for the Earth to be a profoundly spiritual matter . . . Humans, in service to God, have special roles on behalf of the whole of creation. Made in the image of God, we are called to care for the Earth as God cares for the Earth. God’s command to have dominion and subdue the Earth is not a license to dominate and exploit.”

Jewish: As of this writing, the most recent Jewish declaration on the environment was organized by the Jewish Council for Public Affairs and is called the The Jewish Environmental and Energy Imperative Covenant. “…As people of faith: We are fully aware that the issues before us impact all Americans – indeed, all Earth’s inhabitants. We weep at the heavy burden that climate change imposes on the world’s poor, we mourn its impact on the diversity of God’s creations, we tremble at the harm we impose upon our own descendants – and we are alarmed by our own vulnerability, here and now….” Also, many Jewish scholars and rabbi’s have contributed to the Assisi and other religious documents on the environment.

Methodist: They adopted a doctrinal statement on “The Natural World”, including concise statements on the use of water, soil, energy, food, etc. “All creation is the Lord’s,” it reads “and we are responsible for the ways in which we use and abuse it. Water, air, soil, minerals, energy resources, plants, animal life, and space are to be valued and conserved because they are God’s creation and not solely because they are useful to human beings. Therefore, we repent of our devastation of the physical and non-human world. Further, we recognize the responsibility of the Church toward lifestyle and systemic changes in society that will promote a more ecologically just world and a better quality of life for all creation.”