Stir Up Sunday

Christmas Pudding

Mr. Tyler Storey

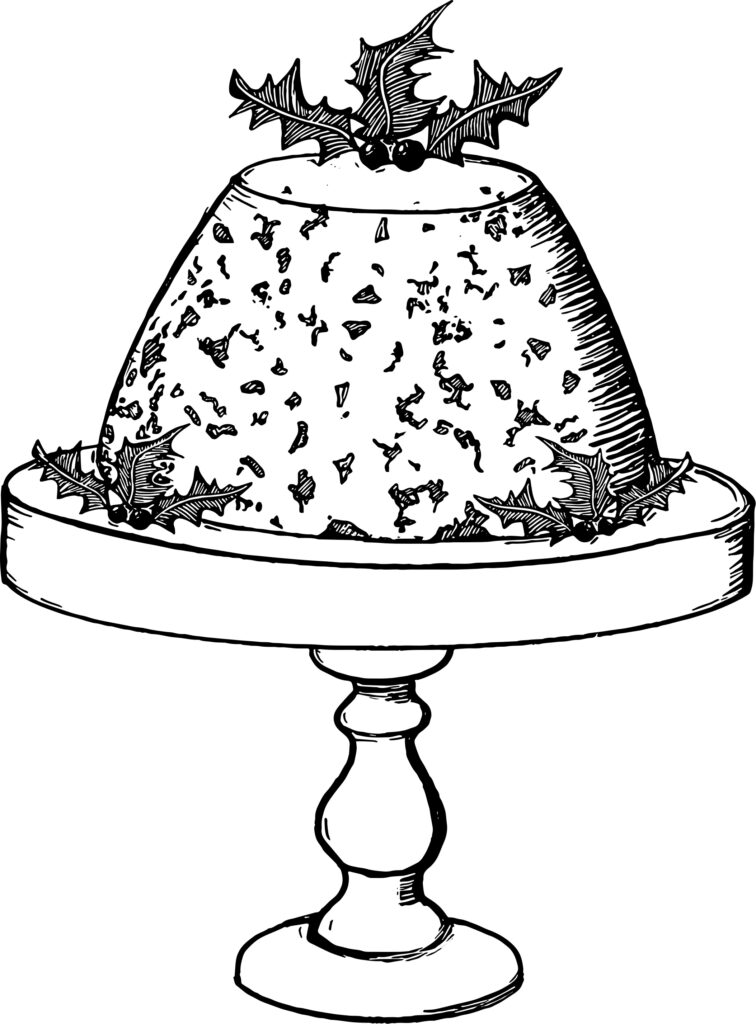

When Bob Cratchit in A Christmas Carol praises his wife’s pudding as the greatest success achieved by Mrs. Cratchit since their marriage, he might have included Charles Dickens in his praise. In his description of the pudding’s passage from laundry-copper to the Cratchit’s Christmas feast, Mr. Dickens joined together Christmas and the celebratory plum pudding in the popular imagination. Within two years, Eliza Acton had published the “author’s recipe” for Christmas Pudding in her popular cookery book, and a grand tradition was cemented in the Victorian British mind.

A proper Christmas pudding requires preparation weeks in advance, so at some point Stir Up Sunday became part of the tradition. Stir Up Sunday takes its name from the collect, or prayer, of the Anglican order of service for the last Sunday before Advent, which in turn is a translation of the Roman Catholic collect of the same day: Excita, quáesumus, Dómine, tuórum fidelium voluntátes: ut divíni óperis fructum propensius exsequentes; pietátis tuae remedia majóra percipiant. “Stir up, we beseech Thee, O Lord, the wills of Thy faithful to seek more earnestly this fruit of the divine work, that they will receive more abundantly healing gifts from Thy tender mercy.”

That Sunday is the last at the end of the liturgical year, and the collect expresses a certain impatience, the excitement of looking forward to the new beginning, the anticipation of the good things to come. The Christmas pudding captures that anticipation perfectly, the culinary expression of Advent. And, as the tradition goes, hearing those words every cook and wife would be distracted from her devotions just long enough to realize that today is the day to make that Christmas pudding, to stir up the fruits that will spend the next five weeks becoming her crowning gift to the Christmas dinner.

When I was a boy and had tasted plum pudding only on the pages of books, I was fascinated by the magnificence and celebration that the plum pudding evoked. As an American boy, I imagined plum pudding as smooth, and purple, and probably served in a cup; a sort of squashy prune custard. The two ideas seemed irreconcilable, which only added to the mystery and attraction. As it turns out, pudding is a generic term for what Americans call dessert, but can specifically mean a cake of sorts, steamed in a mold. The plum of plum pudding is not a plum, but a raisin, although traditional recipes for plum puddings call not for raisins, but for currants, by which is meant raisins.

The vocabulary of the Christmas pudding is complicated, but the recipe is simple, requiring only two cooking techniques: stirring and steaming. Stirring is the defining act of the Stir Up Sunday tradition: the family gathers in the kitchen to make the pudding, and, once all the ingredients are combined, each member of the family takes a turn stirring the batter while making a wish, stirring from East to West to honor the journey of the Magi.

Steaming can be unfamiliar to American cooks, but is a wonderful cooking technique, worth exploring at any time of year. Steaming allows the desserts that we might usually put in the oven to be cooked on the stovetop, with delightful results. And it is forgiving: a few minutes too long in the oven and a baked cake is ruined; an extra half hour of steaming a pudding is no problem.

As this recipe was originally adapted from a Scottish recipe, all the quantities are listed by weight, in grams. The given volume equivalents are approximate, but close enough to give the same results. This is a somewhat elastic recipe and a raisin more or less won’t make much difference; unlike Mrs. Cratchit, you needn’t have any doubts about the quantity of flour.

— Tyler

Christmas

Pudding

What You Need

Equipment

Pudding basin (see Notes)

A lidded pot for steaming, large enough to contain the pudding basin

Trivet, for the steaming

Parchment or wax paper, foil, and kitchen twine

Ingredients (See Notes)

220 grams (1 1/2 cups) Zante currants, or raisins

220 grams (1 1/2 cups) golden raisins

120 grams (1 cup) dried tart cherries

140 grams (3/4 cups) dried plums, chopped

150 milliliters (2/3 cup) Spanish brandy

125 grams (1 cup) suet, shredded

100 grams (3/4 cup) flour

125 grams (1 cup) plain bread crumbs

1/2 teaspoon salt

1 quince, cored but unpeeled

1 teaspoon ground cinnamon

1/4 teaspoon ground cloves

1/4 teaspoon ground ginger

1/2 nutmeg, grated

110 grams (1/2 cup) dark brown sugar

220 grams (1 1/2 cups) candied orange peel, chopped

150 milliliters (2/3 cup) stout or porter

3 large whole eggs

A bit of butter and flour for the pudding basin

More brandy, for curing and serving

What You Do

Advance Preparation:

The day – or up to a week – before, toss together the raisins, cherries, and plums in a small bowl. Pour over the brandy, cover tightly, and allow to macerate until you are ready to mix the pudding.

Directions:

On Stir Up Sunday, lightly butter and flour your pudding basin, and set your pot with a few inches of water to heat on the stove. Set a kettle to boil with additional water.

Toss together the suet, flour, breadcrumbs, and salt in a small mixing bowl.

Grate the quince into a good-size mixing bowl, using a large to medium grater; you are looking for shreds, not mush. Toss the cinnamon, cloves, ginger, nutmeg, and sugar with the shredded quince. Add the raisin mix with all of its liquid, and the candied peel, and stir together.

Toss the flour and suet mixture into the fruit, half at a time, until evenly distributed.

Stir in the porter, and then the eggs, one at a time.

This is the traditional point at which each member of the family gives the pudding a stir and makes a wish. If you have a large family, be careful not to over mix. The batter will be very thick and look perhaps rather unpleasant. But it will smell wonderful; it is the fragrance of Christmas Yet To Come.

Place a small circle of wax paper to cover the bottom of the pudding basin. Spoon the batter into the pudding basin, smooth down the top, and cover with another round of parchment or waxed paper cut just to cover the batter surface.

This part is far more complicated to describe than it is to do: To cover the pudding basin, cut another piece of wax paper, large enough to cover the pudding basin and extend several inches down the side, and a piece of foil the same size. Lay the foil on top of the wax paper, and fold them together in the center with a pleat of about a half-inch width; think of this as the expansion joint for when the pudding is steaming. Lay this lid over the pudding, foil side up, and smooth it down over the basin, keeping the pleat folded. Using a very long piece of kitchen twine, tie this lid to the basin just under the “lip” on the side of the basin. Tie tightly, as this will protect the pudding batter from boiling water and steam. If you wish, loop up the ends of the twine to make a handle.

Place a trivet in the bottom of your pot of boiling water, put the filled and sealed pudding basin on top of that, and top up with water from the kettle so the water comes about half-way up the side of the basin, but below the lid. Cover the pot and steam for about four hours. Check occasionally to be certain there is plenty of water. Top up with boiling water from the kettle as needed.

After four hours, lift the pudding basin from the pot, and place it on a rack to cool for about a half hour.

Once it has cooled a bit, loosen the lid, move aside the parchment round, and dab or dribble about a tablespoon of brandy over the top of the pudding. Replace the parchment and lid, and store in a cool place.

Every few days until Christmas, open up the pudding and dab on another tablespoon of brandy, resealing after.

Serving:

On Christmas, place the pudding back in the steamer, being certain the lid is tied on tightly, and again steam as above for three hours, until the pudding is hot through.

Remove the lid and parchment from the basin, dry the basin, place your flame-proof serving plate upside-down on the top, then invert to unmold the pudding. Remove the small piece of paper from the now-top.

Warm a couple of tablespoons of brandy, pour over the pudding, and — observing every caution — light the pudding with a long match, then carry it flaming into the dining room. When the flames have died down, place a sprig of holly on top, then slice and serve, with a hard sauce if you wish. Do not light yourself, the furniture, or any family or friends on fire.

Variations:

Reading the Notes below, you will see that you can vary the dried fruits and liquor to make the recipe your own. We use dried cherries and plums to add a depth of flavor, and candied orange peel blends well with these and the somewhat sharp character of Spanish brandy. The stout adds a dark layer. If you, for example, use dates or dried apricots, you might then instead use candied lemon peel to add a certain brightness, and bourbon to cut their sweetness. Whatever combination you use, consider how all the flavors will blend together.

Notes:

Pudding basin: The pudding basin is really just a crockery mixing bowl, sturdy enough to take the heat of boiling water, with an upper edge that extends a bit down the bowl to provide an anchor for the string. If you have a lidded metal pudding basin, use that instead, but store the pudding in a non-reactive container between Stir Up Sunday and Christmas, as the pudding and its liquor can corrode metal.

Dried fruit: Zante currants, a small, very flavorful raisin, are the traditional raisins for Christmas pudding; use them if you can find them. If they are unavailable, ordinary raisins will do. The traditional pudding uses only Zante currants and raisins, but here we have varied the flavor a bit by using dried cherries and dried plums for a portion. You can experiment with other dried fruits of the sugary sort, such as dates, figs, or apricots; just be certain to chop them, and aim for a total weight of dried fruit of about 700 grams, with at least half raisins.

Liquor: Brandy is the traditional liquor; we use Spanish brandy because we usually have it on hand and like the subtle sherry note. And because of Ernest Hemingway, but that’s neither here nor there. You might experiment with Calvados, dark rum, or bourbon, and port, sherry, or perhaps marsala will work well; don’t use other whiskies or anything herbal in flavor.

Suet: Do try to get real suet, the fat from around beef kidneys. Check with your butcher, or look for the boxed stuff in the imported food section of the grocers. Suet is a hard fat with a very high melting point; steamed, it melts after the batter has begun to set, and lends a lovely texture to the finished pudding without the slightest meat flavor. Frozen and shredded vegetable shortening might be your best substitute. Butter will taste good, but the pudding will be denser and a bit oily.

Quince: If you can find a fresh quince, do use it; it adds a wonderful perfume to the pudding. Either an apple or a pear will do as a substitute.

Peel: This is the thick candied peel, not thin zest. Around here, we make candied peel throughout the year, whenever we juice oranges or lemons, but you can use store-bought orange or mixed peel, as it’s called.