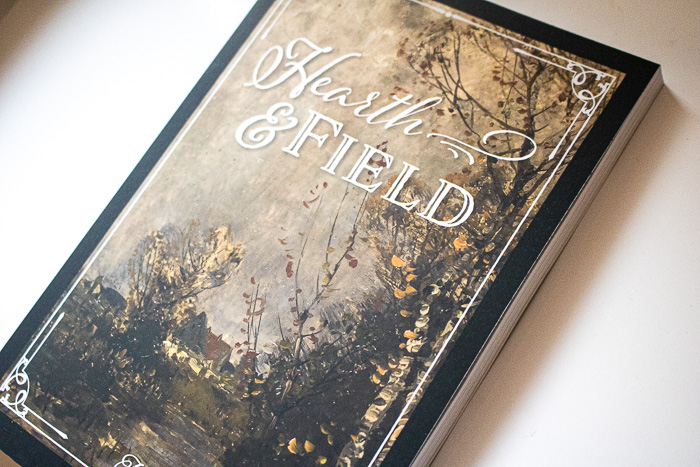

Good Things in

This Country

Seven Suggestions for

Simple Hospitality

Mrs. Sarah Reardon

In the early weeks and months of my marriage, I was determined to practice the very finest hospitality. My grand vision of hosting as a newly married woman knew few bounds. Never mind that I was teaching full-time and my husband was taking classes. Never mind that we were (and still are) a busy young couple living in a city apartment on a budget befitting our stage in life. We both desired (and still desire) to serve our church and community through hospitality; but in hindsight, we didn’t yet understand what true hospitality was, nor how simple it could be.

I recall with some chagrin my attempts to play the part of a resplendent homemaker in those early months, a perfect hostess who would serve exquisite entrees, perfectly paired side-dishes, and stunning desserts, while also curating stellar conversation that would stick with our guests. I spent whole afternoons laboring over those meals, and I always felt a keen sense of stress as the afternoon inched toward evening and I had still not made all I wanted (nor cleaned up enough) to meet my own stratospheric standards. I desired not only to welcome and please my guests but to do so in a way that spotlighted my own spirit and skill. While I convinced myself that I was working from generosity, I was also working from prideful perfectionism, and prideful perfectionism naturally produces stress.

I spent whole afternoons laboring over those meals, and I always felt a keen sense of stress as the afternoon inched toward evening and I had still not made all I wanted (nor cleaned up enough) to meet my own stratospheric standards.

Fortunately, however, it wasn’t long before I began to learn about a different type of hospitality, an approach that would transform my attitude as a hostess. This was largely due to two timely examples that entered my life: one literary and one lived.

The first came from a scene in Tolkien’s The Two Towers, the second book in The Lord of the Rings trilogy. For much of the book, the reader wanders with Frodo and Sam as they trudge through trial after trial, making their way through the shadow of death, accompanied by that sniveling and ghastly creature, Gollum. But as the dark book wends toward its bewildering close, Tolkien offers his reader several shafts of marvelous light, hints of hope. One of these comes in the form of a hot rabbit stew.

In this particular incident, Sam, Frodo, and Gollum have stopped to rest beside a lake as they journey toward Mordor. Sam, feeling especially hungry himself but also motivated to help sustain Frodo, his master and friend, cherishes the idea of making a good meal but has not had the chance (nor the means) to do so for quite some time.  So at this dark moment, with rabbits that Gollum has caught, the cooking gear that Sam “still hopefully carried,” and herbs gathered from near their camp, Sam gives up his own rest in order to prepare a stew to share with his sleeping master.

So at this dark moment, with rabbits that Gollum has caught, the cooking gear that Sam “still hopefully carried,” and herbs gathered from near their camp, Sam gives up his own rest in order to prepare a stew to share with his sleeping master.

Sam lets the rabbits cook for about an hour, poking at them and watching over them, as any good cook would. Finally, he wakes Frodo. This passage follows:

“Hullo Sam!” [Frodo] said. “Not resting? Is anything wrong? What is the time?”

“About a couple of hours after daybreak,” said Sam, “and nigh on half past eight by Shire clocks, maybe. But nothing’s wrong. Though it ain’t quite what I’d call right: no stock, no onions, no taters. I’ve got a bit of a stew for you, and some broth, Mr. Frodo. Do you good. You’ll have to sup it in your mug; or straight from the pan, when it’s cooled a bit. I haven’t brought no bowls, nor nothing proper.”

In this simple, brief interchange, Sam’s hospitable heart for his master positively shines.

Tolkien continues:

Frodo yawned and stretched. “You should have been resting, Sam,” he said, “And lighting a fire was dangerous in these parts. But I do feel hungry. Hmm! Can I smell it from here? What have you stewed?”

Sam and Frodo then relish the rabbit stew, which “seemed a feast” to the weary travelers.

Sam’s gift to Frodo exemplifies the virtue of simple hospitality: Sam possesses meager means but strives to be lavishly generous with them nonetheless. Sam’s attitude throughout the preparation of the meal and its consumption in fellowship with Frodo is also one of hope: “I’ll bet there’s all sorts of good things running wild in this country,” he says to himself as he cooks. His optimism bears fruit — he who seeks does indeed find good things (in this case, herbs and Gollum’s rabbits), though he does not find an abundance. Sam makes a beautiful offering despite having little to begin with and little finally to offer.

Tolkien thus deftly reminds us that a hospitable spirit does not require finery, but contents itself to make do with what there is. Or as Rosaria Butterfield once put it, “Hospitality shares what there is, that’s all.” And when there is nothing at all, as in Sam’s case, a hospitable spirit goes seeking what good things there may be lying about, taking what little there is and multiplying it. Granted, most men cannot feed a crowd with a few loaves and fish (as one eminently hospitable man once did), but any ordinary man or woman may take a meal as simple as bread and fish and multiply its significance, if not its size, expanding its gift by making and serving it with generous love and diligent care. This is the true heart of hospitality: giving simple things with honest welcome, giving ourselves by making use of whatever means we have. Not, as I had mistakenly attempted, trying to host at a level of perfection that borders on impossibility.

My husband and I also learned something about simple hospitality from some real-life hosts in those first months of our marriage. We had recently made friends with an immigrant family, and they had invited us over to celebrate their son’s birthday. When we arrived at their row home, I noticed that though our hosts had obviously worked hard to prepare for the party — the table boasted an abundance of food, and cheerful birthday decorations adorned the walls — an air of relaxed and down-to-earth friendliness nevertheless pervaded the room. The hostess had prepared a large pot of chicken and rice and served it alongside crackers, chips, and candy. Another family had brought a homemade cake. Children, raising voices and making messes, ran about barefoot; adults, in the absence of a dining table, sat on the couch and talked. Due to a language barrier, we couldn’t converse much with our friends, but we understood one another all the same, especially in the genuinely hospitable atmosphere of that evening’s birthday party. The spirit in that row home was not one of grandeur, but rather of the hosts’ overflowing goodwill and gladness. This experience of hospitality warmed us to the core.

After the party, I thought back on many other examples of what I might call true or rightly ordered hospitality from my past: my grandmother hosting neighbors, workmen, or church friends for a breakfast of eggs and toast in her flat; a college couple reserving a dorm kitchen to make and share spaghetti with a motley gathering of fellow students; professors hosting students for a pancake breakfast; and the wide range of people — from older couples with health conditions to young couples with scant budgets — who have readily burdened themselves to host my husband and me for a meal. None of these hosts were fixated on perfection or creating the appearance of grandeur. They shared fully what there was — and that was all. These good hosts gave of what they had without aspiring to something more and thus something unattainable; they gave both of themselves and of their means with attention and care but without perfectionism. Some of this hosting was what you might call fancy, and some was not — but that is not the point. A certain level of finery has its place, of course, and can make for lovely hosting. But what is irreplaceable is the spirit of a hospitable heart.

None of these hosts were fixated on perfection or creating the appearance of grandeur. They shared fully what there was — and that was all. These good hosts gave of what they had without aspiring to something more and thus something unattainable; they gave both of themselves and of their means with attention and care but without perfectionism. Some of this hosting was what you might call fancy, and some was not — but that is not the point. A certain level of finery has its place, of course, and can make for lovely hosting. But what is irreplaceable is the spirit of a hospitable heart.

None of these hosts were fixated on perfection or creating the appearance of grandeur. They shared fully what there was — and that was all.

With time, I too have begun to learn to share what I have instead of striving to share that which is beyond me (and thus failing to share much of myself at all). Along this journey toward a purer and simpler hospitality, I have come to appreciate a number of lessons of hospitality that may be helpful as a guide for those seeking a more peaceful, authentic way to host. I, who have been a homemaker for but a short while, do not presume to teach the arts of hospitality, but only to share what I myself have learned.

1. Accept that less can be enough. Hard though it may be, it is important that the hospitable heart learn to resist the lusty consumerist spirit that longs ever after more. God bestows upon each a certain lot and guides us each through certain seasons of life. We must be content in our current stations; we must be content both to make do with and to share what we have. Though we should strive for excellence in all our endeavors, including the endeavor of hospitality, excellence ought not to be pursued for our own glory, but for the glory of God and the good of our neighbors.

2. But still aim to do well within your means. Embracing simple hospitality does not mean embracing lazy hospitality. Seek to cook and bake and host well, even with little. We may be tempted to throw up our hands and order pizza whenever guests come over. Pizza at the front door, on occasion, can be a marvel, but such marvels grow old far more quickly than homemade meals do. Making do with what one has doesn’t mean avoiding preparation entirely or exhibiting a lack of attention and care; like Sam in The Two Towers, even if all we can give is a bit of stew, we should try to make it a tasty stew (rabbit or otherwise) if we can.

3. Recall your real purpose. The higher purpose and the true heart of hospitality is giving to, loving, and serving others. This, fundamentally, is what I missed in my early attempts at hosting. In hosting we are ultimately imaging our Lord, who gathered his disciples around a table and gave his very body and blood to them. Let your decisions about menus and decor come forth from that purpose.

4. Host often. As my husband and I have hosted frequently in the last year or so — at least once a week — we have grown in our comfort and flexibility as hosts, and I have grown much in my experience as a cook. Practice doesn’t make perfect, but practice does prepare us. Practice has trained me to focus less on myself or even the meal and more on the opportunity for fellowship that lies before me.

5. Embrace the wide variety of options for frugality when it comes to hosting. You can host a breakfast-for-dinner or a Sunday brunch. Chili, chicken soup, grilled cheese and tomato bisque – all these, made and served with care and kindness, can be a lovely choice for a shared meal. Potlucks, too, allow for larger crowds without a larger cost.

6. Practice hospitality outside of the home. Hospitality is less about sharing a particular place than about the spirit of loving welcome that ancient Greek culture honored as xenia, a virtue central to the well-being of the community. This ancient conception of hospitality involved readiness to care for guests, especially strangers. But a spirit of xenia is not limited to the home; rather, any interaction can be an opportunity for hospitality. Bring a snack to share at a gathering of friends or even bring a homemade dessert to work. Make a meal for a struggling family. Check in on your neighbors, especially your elderly neighbors. Greet people you see at the park. There are so many beautiful, simple ways that we can extend welcome to others.

7. Accept the mess. My father often calls relationships “a mess worth making,” riffing on the title of a popular book. Homemakers naturally want to avoid messes, but hosting is a mess worth making, literally and figuratively. You may find stacks of dirty dishes in the sink after hosting a meal or a load of weariness on your shoulders after a guest shares an hour’s worth of personal issues with you. Such messes, though burdensome, represent the natural result of welcoming and caring for broken people. They are evidence of a life generously lived.

As I grow in hospitality, I see how far I have yet to go; while I once found this discouraging, I now see it as an exciting prospect. With each new skill I develop, I recognize another skill or attitude in which I still need to grow – for example, in hosting more often or in welcoming my guests with an increasingly joyful spirit. This is as it should be, for no one ever truly “arrives” in her journey toward cultivating a heart of generosity and true hospitality. So as we look toward the autumn and winter holidays, we might each consider how we may pursue a purer, simpler hospitality. Sam warmed Frodo’s stomach and heart with wild rabbits and foraged herbs, but most of all with his humble generosity. What good, simple things are running wild about us that we might share with others?