Point Me

to the Skies

Dr. Anthony Esolen

Someday, I dearly hope, we will begin to ask what we can do to make our medicine more human. We might begin with the hospital.

“Tommaso, Tommaso!” cried the old woman down the hall. She could speak nothing but Italian. “Voglio andare a casa!” she said, over and over, weeping, for at least an hour while the nurses tried to calm her down. She was terrified.

I wasn’t too pleased, myself. I lay in a hospital bed in a big well-lit room, with a lot of traffic nearby. For the first three or four days, there was an old man in the bed opposite mine, and in the daytime we played a few games of casino, which my father had taught me to pass the hours. My father and mother couldn’t be around much of the time, because the hospital was in Philadelphia and we lived two hundred miles away, so he had work to see about, at least over the phone. But they came when they could, and when the hospital let them. I was alone the rest of the time, except when the doctors had me in for tests to find out what was wrong with my bad leg.

I hadn’t known how bad the leg was. I guess nobody did. We could see the big birthmark, and we knew there were odd veins, and the leg was always warm to the touch. In fact, if that leg is ever cold, the rest of my body must be in a perfect deep freeze. But one morning, at school, all on a sudden, the leg was racked with the most excruciating pain you will ever feel, and I had a fever raging, with chills that made my teeth chatter and my body constrict itself into a knot. My uncle had to get me home immediately. The fever was one hundred and four. It was my first attack of lymphangitis, the first of what I would go on to experience about once a year for the rest of my life. I’ve had one or two that were worse than that first one, but none so terrifying. The local doctor got my fever under control, but the leg was still swollen and suspicious-looking, so he sent me to Philadelphia to be checked out by one of his former teachers at the University of Pennsylvania. And there I was.

I hadn’t known how bad the leg was. I guess nobody did. We could see the big birthmark, and we knew there were odd veins, and the leg was always warm to the touch. In fact, if that leg is ever cold, the rest of my body must be in a perfect deep freeze. But one morning, at school, all on a sudden, the leg was racked with the most excruciating pain you will ever feel, and I had a fever raging, with chills that made my teeth chatter and my body constrict itself into a knot. My uncle had to get me home immediately. The fever was one hundred and four. It was my first attack of lymphangitis, the first of what I would go on to experience about once a year for the rest of my life. I’ve had one or two that were worse than that first one, but none so terrifying. The local doctor got my fever under control, but the leg was still swollen and suspicious-looking, so he sent me to Philadelphia to be checked out by one of his former teachers at the University of Pennsylvania. And there I was.

It was my first attack of lymphangitis, the first of what I would go on to experience about once a year for the rest of my life. I’ve had one or two that were worse than that first one, but none so terrifying.

I guess that things would be different today, in two ways, one good, one bad. The hospital would be cleaner, and perhaps more efficient. That’s good, generally. I recall one day I was supposed to get a venogram, and at that time it required the injection of dye that made my whole body feel icy cold, and I was to be fixed on a slanted table, not moving a muscle while the dye made its way through my veins. It took a long time to do that. Meanwhile, nobody had told me that I should make sure to use the bathroom beforehand, so for the next fifteen years, until I finally discovered it on the medical record and dispensed with it, doctors saw that I had a strangely enlarged bladder. Sure — when they said, “Don’t move,” I didn’t move.

Another one of the tests, I believe the arteriogram, was wickedly painful and hot. I think that was the one where they inserted tubes into the tops of my feet. I have the scars from the operation the doctor had to perform. This time the dye made me feel as if I were being scorched from inside, and it hurt so bad I would burst out laughing. The doctor was impressed by that, as I remember. I told him that I couldn’t explain it, but that’s what the pain made me do. He shrugged and took it as a good sign.

They didn’t make a firm diagnosis, and sure enough, I returned to the same hospital a year later, and this time it kept me out of school for a month, a silver lining if there ever was one. I was then instructed to take penicillin every day, apparently for the rest of my life, and to wear a heavy-duty compression stocking on that leg, to squeeze it and help the blood and the lymph to flow upward, rather than pooling in the lower leg and breeding infection. I no longer take antibiotics every day, but I do keep them on hand always, and I do put on the compressor when I get out of bed. I was once told by a vascular surgeon that I have the worst case of my syndrome that he’d ever seen, but that I’d also taken the best care of it.

That hospital was, at that time, the most horrible place I’d ever been, but I think I’d still take it over what hospitals are now. It was, how to put it, an inhuman place where people tried hard to be human anyway. There were fewer machines droning or humming or beeping in the old hospital, and if there was a television in my room, I don’t recall it. The machines that drone or hum or beep are certainly good for keeping you alive, but not so good at persuading you that you ought to be. And then there’s the morphine drip, not a feature of the old hospital, but a regular feature of the new, meant to suppress your breathing and ease you off into the next world, comfortably, painlessly, as if you were a dog or a cat, and not man made in the image of God.

The machines that drone or hum or beep are certainly good for keeping you alive, but not so good at persuading you that you ought to be.

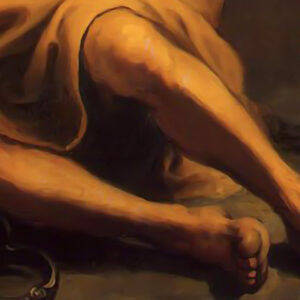

I suspect that a lot of people are more afraid of the hospital than they are of dying. We shouldn’t regard their fears as merely irrational. Think of what you would have seen if you were a patient in the hospital of Holy Charity, in Seville, when Bartolome Esteban Murillo was commissioned to cover the walls of the chapel with paintings depicting charity in action, from the Scriptures and the lives of the saints.  You look up, and there is the prodigal returning home to the father who embraces him, while servants are nearby with rich robes to replace the rags that hardly cover his nakedness, and a little white dog, man’s best and most faithful friend, leaps at the boy’s feet to welcome him home. Or you see the old Saint Peter, in the deeps of a prison, his chains burst open, as an angel in the bloom of youth is about to take him by the hand and lead him to liberty.

You look up, and there is the prodigal returning home to the father who embraces him, while servants are nearby with rich robes to replace the rags that hardly cover his nakedness, and a little white dog, man’s best and most faithful friend, leaps at the boy’s feet to welcome him home. Or you see the old Saint Peter, in the deeps of a prison, his chains burst open, as an angel in the bloom of youth is about to take him by the hand and lead him to liberty.

Won’t that mean more to you than the television, or the intercoms and their incessant boredom punctuated by urgency? Won’t you feel more at home, or rather that the place was a good way-station in your pilgrimage to return home, or to go to the true home you have never seen, but only felt, like a dim memory or vision? And imagine that you occasionally hear, not the shrieks of mirthless laughter coming from the program that poses as entertainment (though is actually crude politics), but a song, a hymn, or the chant of prayer. And when the church bell tolls, it is solemn, not dreadful, and yet sweet, not sickly, and it seems to come from the foundations of the earth, rising up toward him who laid those foundations.

Can we not, as Christians, build more human places for the sick and the dying? The old lady was terrified because she was alone and she didn’t understand what people were saying to her. Imagine if she had had Christ to gaze upon. Imagine if the old man and I had something more in common than a pack of cards. I suppose that the condition in my leg will one day take me out of this world. When that happens, I had rather be at home, with my family nearby, and the dog sleeping at my feet, and the cross of Christ to look on, to shine through the gloom, as the old hymn puts it, and point me to the skies.

Commissioned for the Hospital of Holy Charity in Seville.