—Ink and Echoes—

On Walking to

(and Away from)

Inns

Hilaire Belloc

—1911—

So long as man does not bother about what he is or whence he came or whither he is going, the whole thing seems as simple as the verb “to be”; and you may say that the moment he does begin thinking about what he is (which is more than thinking that he is) and whence he came and whither he is going, he gets on to a lot of roads that lead nowhere, and that spread like the fingers of a hand or the sticks of a fan; so that if he pursues two or more of them he soon gets beyond his straddle, and if he pursues only one he gets farther and farther from the rest of all knowledge as he proceeds. You may say that and it will be true. But there is one kind of knowledge a man does get when he thinks about what he is, whence he came and whither he is going, which is this: that it is the only important question he can ask himself.

Now the moment a man begins asking himself those questions (and all men begin at some time or another if you give them rope enough) man finds himself a very puzzling fellow. There was a school — it can hardly be called a school of philosophy — and it is now as dead as mutton, but anyhow there was a school which explained the business in the very simple method known to the learned as tautology — that is, saying the same thing over and over again. For just as the woman in Molière was dumb because she was affected with the quality of dumbness, so man, according to this school, did all the extraordinary things he does do because he had developed in that way. They took in a lot of people while they were alive (I believe a few of the very old ones still survive), they took in nobody more than themselves; but they have not taken in any of the younger generation. We who come after these scientists continue to ask ourselves the old question, and if there is no finding of an answer to it, so much the worse; for asking it, every instinct of our nature tells us, is the proper curiosity of man.

Of the great many things which man does which he should not do or need not do, if he were wholly explained by the verb “to be,” you may count walking. Of course if you build up a long series of guesses as to the steps by which he learnt to walk, and call that an explanation, there is no more to be said. It is as though I were to ask you why Mr Smith went to Liverpool, and you were to answer by giving me a list of all the stations between Euston and Lime Street, in their exact order. At least that is what it would be like if your guesses were accurate, not only in their statement, but also in their proportion, and also in their order. It is millions to one that your guesses are nothing of the kind. But even granted by a miracle that you have got them all quite right (which is more than the wildest fanatic would grant to the dearest of his geologians) it tells me nothing.

What on earth persuaded the animal to go on like that? Or was it nothing on earth but something in heaven?

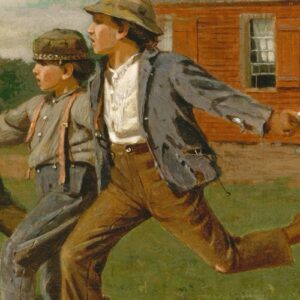

Just watch a man walking, if he is a proper man, and see the business of it: how he expresses his pride, or his determination, or his tenacity, or his curiosity, or perhaps his very purpose in his stride! Well, all that business of walking that you are looking at is a piece of extraordinarily skillful trick-acting, such that were the animal not known to do it you would swear he could never be trained to it by any process, however lengthy, or however minute, or however strict. This is what happens when a man walks: first of all he is in stable equilibrium, though the arc of stability is minute. If he stands with his feet well apart, his centre of gravity (which is about half way up him or a little more) may oscillate within an arc of about five degrees on either side of stability and tend to return to rest. But if it oscillates beyond that five degrees or so, the stability of his equilibrium is lost, and down he comes. Men have been known to sleep standing up without a support, especially on military service, which is the most fatiguing thing in the world; but it is extremely rare, and you may say of a man so standing, even with his feet well spread, that he is already doing a fine athletic feat.

But wait a moment: he desires to go, to proceed, to reach a distant point, and instead of going on all fours, where equilibrium would indeed be stable, what does he do? He deliberately lifts one of his supports off the ground, and sends his equilibrium to the devil; at the same time he leans a little forward so as to make himself fall towards the object he desires to attain. You do not know that he does this, but that is because you are a man and your ignorance of it is like the ignorance in which so many really healthy people stand to religion, or the ignorance of a child who thinks his family established for ever in comfort, wealth and security. What you really do, man, when you want to get to that distant place (and let this be a parable of all adventure and of all desire) is to take an enormous risk, the risk of coming down bang and breaking something: you lift one foot off the ground, and, as though that were not enough, you deliberately throw your centre of gravity forward so that you begin to fall.

That is the first act of the comedy.

The second act is that you check your fall by bringing the foot which you had swung into the air down upon the ground again.

That you would say was enough of a bout. Slide the other foot up, take a rest, get your breath again and glory in your feat. But not a bit of it! The moment you have got that loose foot of yours firm on the earth, you use the impetus of your first tumble to begin another one. You get your centre of gravity by the momentum of your going well forward of the foot that has found the ground, you lift the other foot without a care, you let it swing in the fashion of a pendulum, and you check your second fall in the same manner as you checked your first; and even after that second clever little success you do not bring your feet both firmly to the ground to recover yourself before the next venture: you go on with the business, get your centre of gravity forward of the foot that is now on the ground, swinging the other beyond it like a pendulum, stopping your third catastrophe, and so on; and you have come to do all this so that you think it the most natural thing in the world!

Not only do you manage to do it but you can do it in a thousand ways, as a really clever acrobat will astonish his audience not only by walking on the tight-rope but by eating his dinner on it. You can walk quickly or slowly, or look over your shoulder as you walk, or shoot fairly accurately as you walk; you can saunter, you can force your pace, you can turn which way you will. You certainly did not teach yourself to accomplish this marvel, nor did your nurse. There was a spirit within you that taught you and that brought you out; and as it is with walking, so it is with speech, and so at last with humour and with irony, and with affection, and with the sense of colour and of form, and even with honour, and at last with prayer.

By all this you may see that man is very remarkable, and this should make you humble, not proud; for you have been designed in spite of yourself for some astonishing fate, of which these mortal extravagances so accurately seized and so well moulded to your being are but the symbols.

Walking, like talking (which rhymes with it, I am glad to say), being so natural a thing to man, so varied and so unthought about, is necessarily not only among his chief occupations but among his most entertaining subjects of commonplace and of exercise.

Thus to walk without an object is an intense burden, as it is to talk without an object. To walk because it is good for you warps the soul, just as it warps the soul for a man to talk for hire or because he thinks it his duty. On the other hand, walking with an object brings out all that there is in a man, just as talking with an object does. And those who understand the human body, when they confine themselves to what they know and are therefore legitimately interesting, tell us this very interesting thing which experience proves to be true: that walking of every form of exercise is the most general and the most complete, and that while a man may be endangered by riding a horse or by running or swimming, or while a man may easily exaggerate any violent movement, walking will always be to his benefit—that is, of course, so long as he does not warp his soul by the detestable habit of walking for no object but exercise. For it has been so arranged that the moment we begin any minor and terrestrial thing as an object in itself, or with merely the furtherance of some other material thing, we hurt the inward part of us that governs all. But walk for glory or for adventure, or to see new sights, or to pay a bill or to escape the same, and you will very soon find how consonant is walking with your whole being. The chief proof of this (and how many men have tried it, and in how many books does not that truth shine out!) is the way in which a man walking becomes the cousin or the brother of everything round.

If you will look back upon your life and consider what landscapes remain fixed in your memory, some perhaps you will discover to have struck you at the end of long rides or after you have been driven for hours, dragged by an animal or a machine. But much the most of these visions have come to you when you were performing that little miracle with a description of which I began this: and what is more, the visions that you get when you are walking, merge pleasantly into each other. Some are greater, some lesser, and they make a continuous whole. The great moments are led up to and are fittingly framed. . . .

Walking, also from this same natural quality which it has, introduces particular sights to you in their right proportion. A man gets into his motor car, or more likely into somebody else’s, and covers a great many miles in a very few hours. And what remains to him at the end of it, when he looks closely into the pictures of his mind, is a curious and unsatisfactory thing: there are patches of blurred nothingness like an uneasy sleep, one or two intense pieces of impression, disconnected, violently vivid and mad, a red cloak, a shining streak of water, and more particularly a point of danger. In all that ribbon of sights, each either much too lightly or much too heavily impressed, he is lucky if there is one great view which for one moment he seized and retained from a height as he whirled along. The whole record is like a bit of dry point that has been done by a hand not sure of itself upon a plate that trembled, now jagged chiselling bit into the metal; now blurred or hardly impressed it at all: only in some rare moment of self-possession or of comparative repose did the hand do what it willed and transfer its power. . . . Then there is the way of looking at the world which rich men imagine they can purchase with money when they build a great house looking over some view—but it is not in the same street with walking! You see the sight nine times out of ten when you are ill attuned to it, when your blood is slow and unmoved, and when the machine is not going. When you are walking the machine is always going, and every sense in you is doing what it should with the right emphasis and in due discipline to make a perfect record of all that is about.

Consider how a man walking approaches a little town; he sees it a long way off upon a hill; he sees its unity, he has time to think about it a great deal. Next it is hidden from him by a wood, or it is screened by a roll of land. He tops this and sees the little town again, now much nearer, and he thinks more particularly of its houses, of the way in which they stand, and of what has passed in them. The sky, especially if it has large white clouds in it and is for the rest sunlit and blue, makes something against which he can see the little town, and gives it life. Then he is at the outskirts, and he does not suddenly occupy it with a clamour or a rush, nor does he merely contemplate it, like a man from a window, unmoving. He enters in. He passes, healthily wearied, human doors and signs; he can note all the names of the people and the trade at which they work; he has time to see their faces. The square broadens before him, or the market-place, and so very naturally and rightly he comes to his inn, and he has fulfilled one of the great ends of man.

Lord, how tempted one is here to make a list of those monsters who are the enemies of inns!

There is your monster who thinks of it as a place to which a man does not walk but into which he slinks to drink; and there is your monster who thinks of it as a place to be reached in a railway train and there to put on fine clothes for dinner and to be waited upon by Germans. There is your more amiable monster, who says: “I hear there is a good inn at Little Studley or Bampton Major. Let us go there.” He waits until he has begun to be hungry, and he shoots there in an enormous automobile. There is your still more amiable monster, who in a hippo-mobile hippogriffically tools into a town and throws the ribbons to the person in gaiters with a straw in his mouth, and feels (oh, men, my brothers) that he is doing something like someone in a book. All these men, whether they frankly hate or whether they pretend to love, are the enemies of inns, and the enemies of inns are accursed before their Creator and their kind.

There are some things which are a consolation for Eden and which clearly prove to the heavily-burdened race of Adam that it has retained a memory of diviner things. We have all of us done evil. We have permitted the modern cities to grow up, and we have told such lies that now we are accursed with newspapers. And we have so loved wealth that we are all in debt, and that the poor are a burden to us and the rich are an offence. But we ought to keep up our hearts and not to despair, because we can still all of us pray when there is an absolute necessity to do so, and we have wormed out the way of building up that splendid thing which all over Christendom men know under many names and which is called in England an INN.

I have sometimes wondered when I sat in one of these places, remaking my soul, whether the inn would perish out of Europe. I am convinced the terror was but the terror which we always feel for whatever is exceedingly beloved.

There is an inn in the town of Piacenza into which I once walked while I was still full of immortality, and there I found such good companions and so much marble, rooms so large and empty and so old, and cooking so excellent, that I made certain it would survive even that immortality which, I say, was all around. But no! I came there eight years later, having by that time heard the noise of the Subterranean River and being well conscious of mortality. I came to it as to a friend, and the beastly thing had changed! In place of the grand stone doors there was a sort of twirlygig like the things that let you in to the Zoo, where you pay a shilling, and inside there were decorations made up of meaningless curves like those with which the demons have punished the city of Berlin; the salt at the table was artificial and largely made of chalk, and the faces of the host and hostess were no longer kind.

I very well remember another inn which was native to the Chiltern Hills. This place had bow windows, which were divided into medium-sized panes, each of the panes a little rounded; and these window-panes were made of that sort of glass which I will adore until I die, and which has the property of distorting exterior objects: of such glass the windows of schoolrooms and of nurseries used to be made. I came to that place after many years by accident, and I found that Orcus, which has devoured all lovely things, had devoured this too. The inn was called “an Hotel,” its front was rebuilt, the window’s had only two panes, each quite enormous and flat, one above and one below, and the glass was that sort of thick, transparent glass through which it is no use to look, for you might as well be looking through air. All the faces were strange except that of one old servant in the stable-yard. I asked him if he regretted the old front, and he said “Lord, no!” Then he told me in great detail how kind the brewers had been to his master and how willingly they had rebuilt the whole place. These things reconcile one with the grave.

Well then, if walking, which has led me into this digression, prepares one for the inns where they are worthy, it has another character as great and as symbolic and as worthy of man. . . . As for your memories, they are of no good to you except to lend you that dignity which can always support a memoried man; you are bound to forget, and it is your business to leave all that you have known altogether behind you, and no man has eyes at the back of his head — go forward. Upon my soul I think that the greatest way of walking, now I consider the matter, or now that I have stumbled upon it, is walking away.