Many people are finding contentment in the rebellion of homesteading. It is rebellion because it dislodges us from so many machines. By homesteading we say “no” to being a cog in a wheel. Growing food gets you out of ridiculous tax systems and a consumer-based economy at the same time. It makes you a producer. The term economy, after all, means “household management”, not “how much money we wasted consuming as consumers.”

Here’s a bit of my rebellion: I milk a cow.

Yes, every day I rebelliously bring milk from my cow to my family in one easy step. You laugh, but when you consider how long the journey from cow to table takes in today’s industrialized system, you’ll see how revolutionary I’m being. Typically, after milk leaves the cow, it goes to a milk hauler. The hauler takes it to a milk plant, which might ship it to another processing plant. The milk then goes to a distributor, then to a grocery store, and then finally to you. For better or worse, it is through complex supply chains like this that much of the world is fed.

When such a chain of highly specialized dependencies works it works well enough, and can be efficient in a certain sense of the word. But when such a system fails it fails spectacularly. Consider the fact that during this pandemic, many already struggling dairy farmers were forced to dump oceans of milk into manure pits. This was because links later in the chain were unable to receive milk, and so trucks did not arrive to take it, but the cows didn’t much care and went right on producing it.

We saw similar Covid-induced situations in the meat industry. The old-fashioned butcher shop has largely given way to new-fashioned meat processing plants that efficiently slaughter tens of thousands of animals each day. When that suddenly stopped in April 2020, upstream agricultural communities were left trying to figure out what to do with tens of thousands of animals. Each day. And of course, through all this, consumers were left unable to find meat or milk on store shelves. Water water everywhere / Nor any drop to drink.

Even when things are not Corona-broken, downsides still exist. Milk loses quality as it is handled, which is why what you buy in the store tastes so different from fresh. Oh, and there are taxes, government fees, association fees (like the ones that fund the silly “Got Milk” campaign), not to mention a lot of people trying to skim some of the cream during milk’s tortuous journey. The only person usually not making much money is the farmer. (Prices paid to farmers right now are about where they were in the 1970s.) Part of those fees and taxes mentioned above fund a government that pays farms not to grow food, and that has advocated for food producers to use more cheese while simultaneously warning consumers against eating too much of it. The system is smellier than Limburger. I don’t propose to solve the world’s food supply chain issues in this article, but, through my little homestead rebellion, I’ve fixed them for my family. You can fix them for yours, too. If everyone did the same, it would — well — fix the world’s food supply chain issues.

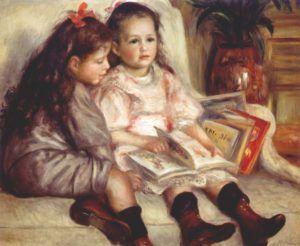

Homesteading can also draw families together in an integrated work. To continue my example of the home dairy project, each family member works at it, benefits from it, and spends time together doing it. The kids and I milk and care for Abigail, our testy — but sweet — Jersey cow. My wife and my oldest daughter make cheese, butter, and so on, and we all enjoy what they make together! We also grow closer to other members of our community as we barter with and learn from one another and when we enlist friends to help our family whenever I have to travel for work (as I sometimes still do, with a Catholic mentoring organization called Fraternus).

Homesteading can also draw families together in an integrated work. To continue my example of the home dairy project, each family member works at it, benefits from it, and spends time together doing it. The kids and I milk and care for Abigail, our testy — but sweet — Jersey cow. My wife and my oldest daughter make cheese, butter, and so on, and we all enjoy what they make together! We also grow closer to other members of our community as we barter with and learn from one another and when we enlist friends to help our family whenever I have to travel for work (as I sometimes still do, with a Catholic mentoring organization called Fraternus).

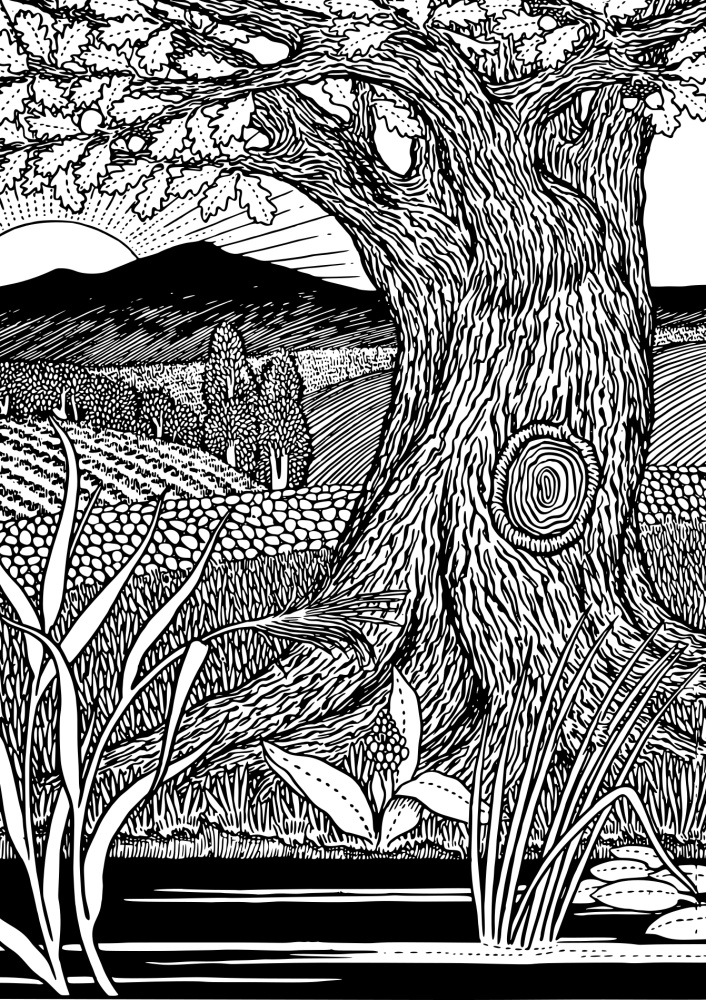

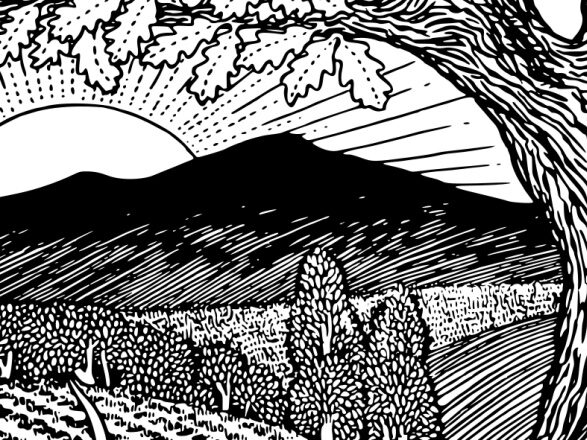

Not everyone can raise cows, of course, but many of us can enjoy bucking immoral food systems while growing closer to our families, spending time in nature (a “book” that God wrote, as so many saints have put it), and doing a work that benefits more than just one’s checkbook, retailers, or the tax collector. In short, it is good. Adam, after all, had a primordial vocation to tend the garden. The garden was created good already by God, but tending and keeping it continues and extends God’s creative power through our work. Cultivating the land is a uniquely blessed activity. No other creature has that dignity because only with man does God share his own dominion and creative power – he even lets us name the beasts!

Cultivating the land is a uniquely blessed activity. No other creature has that dignity because only with man does God share his own dominion and creative power – he even lets us name the beasts!

We have grown a wide variety of plants and animals in our stumbling attempt at farming. We have seen and talked to people coming and going in this wild world of agrarianism. I can safely say that I have experienced more mistakes than successes, but I’ve certainly learned a lot through them. As I’ve heard it said, failure is compost . . if you know what to do with it. So, with my failures and experience in mind, here are seven tips for those of you just getting started in homesteading:

1. Find mentors.

Don’t spend a bunch of time looking at websites and magazines like “Mother Earth News” – they’re selling advertising, not worthwhile information. It’s sort of like those magazines in the grocery aisle that have an article about “best lovin’ ever” every single month. The wannabe farmer magazines just print pictures of unrealistic and pretty gardens and rolling pastures and say basically the same stuff over and over, just as Cosmopolitan says the same thing over and over again with pretty and unrealistic pictures. Don’t window shop and compare yourself to impossible ideals. Go find someone to learn from! You’ll learn more from driving a couple hours away and spending a day walking around a homestead or farm, than you will by staying up too late googling. Overdoing the “research” part of homesteading can become a paradoxical addiction, where you spend more time inside behind screens reading about being outside than you do outside in front of reality. Visiting a working homestead might also make you realize that you don’t want to homestead – and that’s just fine. You can find other ways to avoid consumerism and enjoy life.

2. Don’t get weird about it.

Don’t do a massive pendulum swing from Walmart shopper to Amish yeoman. Start slow. If you do, you will be less likely to get discouraged by failure or feel embarrassed when you give up and then see your friends at Walmart. Do it because it’s good, not as a sheer reaction or to “prep” for disasters. It will also help if you simply tell your friends about your good homesteading experiences instead of describing the errors of the modern system they are part of. (Oops – is that how I started this article?) In short, just homestead for a while before grandstanding to the world. Homesteading is good, and that is reason enough.

3. Don’t grow exotic things – stick to the classics.

There’s a reason every old picture of a farm includes chickens, cows, and pigs – these things produce food! If your goal is to raise enough food to actually feed your family, pigs and cows (dairy or beef) — not chickens — are your best bets. They supply abundant food for a family. The cost of raising chickens is actually very hard to justify. After feed and other expenses, you don’t really fare any better than just buying eggs at the store. On the other hand, the act of caring for them is good, and they are useful for other aspects of the farm (see my next point). And, as chicken owners will tell you, chickens are extremely entertaining.

Sticking with the classics applies to vegetables as well. Your family can grow (and will likely enjoy) squash, tomatoes, beans, potatoes, and other classics much more than obscure and eccentric plants. These classics also tend to have varieties that are hardy and more forgiving. In sum, grow corn and pigs at first, not bok choy and llamas — no matter what Mother Earth News or the Farmers’ Almanac (or Hearth & Field) said in their latest issue.

4. Think in whole systems.

Don’t just picture your place with a cage here, a pen here, and a garden here. Think of how they all work together and how they can mutually benefit each other. Make your systems versatile and movable. Ask first what the land would like to do, not what you can force it to do. I have pigs under oak trees to eat the acorns next to the cows’ barn where they can also drink spoiled milk or waste from dairying. Both of them are kept above a pasture and garden space, so that, when it rains, their nutrients flow into that area and fertilize it. I also use pigs to till my garden spaces and to clean out areas in general. On a smaller scale, you might consider having chickens or compost piles on top of future garden spaces so that when you move them, you have more fertile ground to work with. In these early stages, books in the “permaculture” style of farming will be the most helpful.

5. Never have naked soil.

The number one mistake I see people make tilling up huge spaces on a warm Saturday before they really have a plan or enough experience gardening on a scale bigger than a pot. No really, this happens all the time. I use tilling and layering techniques that create better soil, less work, and more fertility. (It’s not the only way, but it works very well). Nature never allows soil to be bare. Naked soil will wash away, compact, and lose fertility fast. That’s why after you till, all sorts of new weeds pop up. They are trying to cover that naked ground fast, doing exactly what they were designed to do. There are no weeds in the forest where old leaves keep the floor mulched, but dormant weed seeds are there in case they are ever needed. Imitate the forest. Keep your ground covered in mulch or cover crops and only disturb it for really good reasons. I use cardboard and straw (not hay) as mulch, and then pile up manure and compost on top of that, then maybe some leaves, then more straw. I usually do this in the wintertime so that, come spring, the worms have “tilled” the soil, cardboard, and compost altogether and the weed seeds are eight inches underground instead of on top and ready to sprout when you water those new lettuce seeds. If you want a new garden space fast, put down a layer of cardboard and a load of compost and let it sit for a while, then work up small areas right where you are planting (leave the rest as mulch and future soil), then plant and mulch with straw.

The number one mistake I see people make tilling up huge spaces on a warm Saturday before they really have a plan or enough experience gardening on a scale bigger than a pot. No really, this happens all the time. I use tilling and layering techniques that create better soil, less work, and more fertility. (It’s not the only way, but it works very well). Nature never allows soil to be bare. Naked soil will wash away, compact, and lose fertility fast. That’s why after you till, all sorts of new weeds pop up. They are trying to cover that naked ground fast, doing exactly what they were designed to do. There are no weeds in the forest where old leaves keep the floor mulched, but dormant weed seeds are there in case they are ever needed. Imitate the forest. Keep your ground covered in mulch or cover crops and only disturb it for really good reasons. I use cardboard and straw (not hay) as mulch, and then pile up manure and compost on top of that, then maybe some leaves, then more straw. I usually do this in the wintertime so that, come spring, the worms have “tilled” the soil, cardboard, and compost altogether and the weed seeds are eight inches underground instead of on top and ready to sprout when you water those new lettuce seeds. If you want a new garden space fast, put down a layer of cardboard and a load of compost and let it sit for a while, then work up small areas right where you are planting (leave the rest as mulch and future soil), then plant and mulch with straw.

6. Compost is not optional.

Whether you make compost or buy it, an investment in soil fertility is an investment that will actually pay you back. Don’t overdo it with the seed catalogue and dream up an acre garden before you have the soil to support it. Also, don’t buy ten flats of plants on a whim while you’re running errands before the soil is prepared at home. Soil is a whole system in itself and has more going on than anything else on the farm, from bacteria to minerals – and your homestead needs as many things living and dying in there as possible. Soil is not just a support for the roots of plants, it is where your food begins.

7. Start.

I’ve wanted to have a small dairy for many years now. When I first moved to the country I hounded a mentor – “Teach me how to take care of cows!” He didn’t know exactly what to tell me, but had clearly grown tired of the talk. “Just get a cow, Jason.” So, I got a cow. I started. You don’t have to go from couch potato to potato farmer to receive the blessings of homesteading. You can grow a tomato vine on the patio in a pot, but the simple act and experience will get you going in that direction. Even if your first tomato dies, you can always put it in the compost pile and start again! Hey, maybe you just don’t like homesteading and you’ll decide to try brewing beer at home instead – that’s still human culture! If you go that route, come on over and we’ll barter our goods and enjoy the fruits of the earth and the work of human hands — without being subject to the frailties of an overburdened supply chain or increasing the GDP.