Preserving an Inheritance

Mr. Kirk Wareham

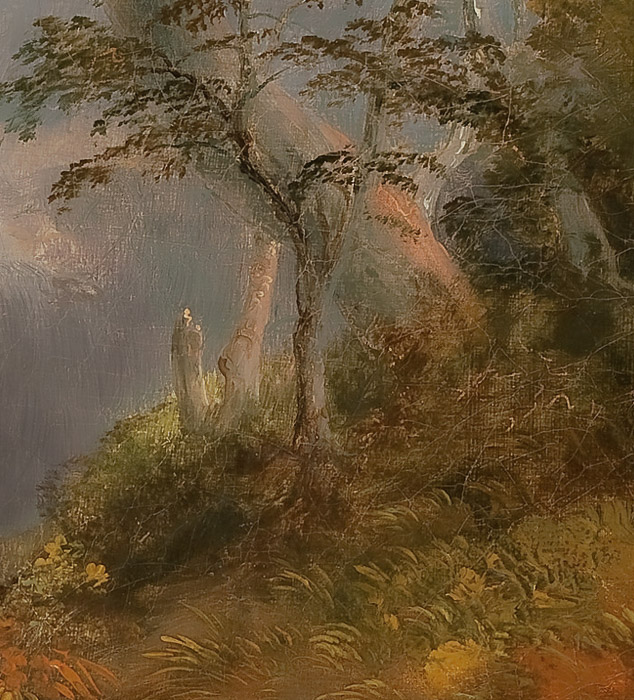

The seasons are turning, as they always are, and I am hiking in the Catskill Mountains with my seven-year-old granddaughter.

We are on official business, which is to say that we are performing trail maintenance for the New York-New Jersey Trail Conference. Our job is to clear the trail of blowdowns, remove fallen leaves from water-bars, collect discarded trash, and report anything else that might concern the suits and ties in the air-conditioned offices in Mahwah, New Jersey.

My granddaughter cheerfully and joyously volunteered for this adventure. She is able, sturdy, and sure-footed, even on the steep jumble of rock slabs that constitute the challenging northwest face of Twin Mountain, one of several peaks along the Devil’s Footpath.

My granddaughter cheerfully and joyously volunteered for this adventure. She is able, sturdy, and sure-footed, even on the steep jumble of rock slabs that constitute the challenging northwest face of Twin Mountain, one of several peaks along the Devil’s Footpath.

Trail maintenance is, in reality, just an excuse to immerse myself in the peace and beauty of nature, a key ingredient in maintaining my mental and emotional health.

For the first half mile, my granddaughter sticks close beside me. When I let go of her hand to toss branches off the trail, her little hand slides back into mine as soon as I am finished. She is, I think, attempting to get her bearings, to find her place in this awe-inspiring wilderness. Holding hands implies hospitality, strength, friendship, belonging, and love — significant graces that we all need in our sometimes-fractured lives.

Holding hands implies hospitality, strength, friendship, belonging, and love — significant graces that we all need in our sometimes-fractured lives.

She is something of a budding naturalist, and we pay close attention to the flowers, ferns, and trees. At low elevation, we find vast patches of Beauty in full bloom, and together we kneel by the trail to examine one exquisite blossom at point-blank range. Inches away, almost unnoticed, stands a timid Yellow Violet.

On a rock the size of a Whirlpool refrigerator, we discover Yellow Specklebelly, a curly brown lichen that looks like moldy potato chips, well salted.

Nearby, she points to a cluster of dainty exquisite ferns. “Maidenhair Spleenwort,” she announces with some authority.

Ov er the next rise, we come to a stream, which cascades down great slanting slabs of conglomerate, fast torrents alternating with dark calm pools where bubbles turn slowly in circles. Rhododendron bushes and fiddlehead ferns line both banks, and together we skip across the stream easily, jumping from stone to stone.

er the next rise, we come to a stream, which cascades down great slanting slabs of conglomerate, fast torrents alternating with dark calm pools where bubbles turn slowly in circles. Rhododendron bushes and fiddlehead ferns line both banks, and together we skip across the stream easily, jumping from stone to stone.

We wander through an abandoned bluestone quarry. Long ago, this quarry and others like it provided huge flagstones for the sidewalks of New York City. Now, only the broken pieces are left behind in piles. Passing hikers seem unable to resist the temptation to build thrones, towers, and walls with the leftovers, which gives the quarry the appearance of a disheveled and abandoned castle courtyard.

Farther down the trail, I lean over and point to a small green leaf.

“What’s this?”

“Goldthread,” she says, without hesitation. The plant sports three shiny green leaves, with a gap where a fourth leaf seems to be missing. The Latin name, I find out later, is Coptis trifolia, in honor of the three leaves.

“Watch,” she says. “If you pull it up, the very bottom of the stem is golden.”

She grasps the small plant, pulls gently, and up it comes. Sure enough, the end of the stem is bright yellow. Her eyes sparkle.

Twin Mountain has two peaks and, from afar, it looks like a corduroy fedora with a dimple in the middle. The Blackhead Range is clearly visible from the north peak, while the south peak overlooks the Hudson River.

Mountain has two peaks and, from afar, it looks like a corduroy fedora with a dimple in the middle. The Blackhead Range is clearly visible from the north peak, while the south peak overlooks the Hudson River.

Each time I reach the south lookout on Twin, I remember meeting a hiker here with only one leg. Using a pair of crutches, he climbed two thousand vertical feet of rugged trail to spend a few minutes enjoying this very view. Two of his friends, who came along for the ride, told me that they had been instructed not to help him at all, and that he had climbed this mountain more than once. Truly impressive!

While I squint at a kettle of hawks circling overhead, my granddaughter discovers a plastic gallon jug, which has been tossed down the bank by a careless hiker. She climbs down and retrieves it, and we add it to the garbage bag in my backpack. I am proud of her determination to leave the mountain cleaner than we found it, as it shows a healthy respect and love for Creation.

More than once, I have completed this trek without finding a single piece of trash along the way. This is remarkable and encouraging. In my experience, hikers have a reverence for all things wild and wonderful; they love nature with heart and soul, are drawn irresistibly to its manifest wonders. Because of this, they carry out what they carry in. And each time I walk here, I am inspired, and my hope is renewed, and my duty is made clear. We should enjoy nature, but we should also take care of it — it belongs to every future generation no less than to our own.

Completing our work for the day, I drop her off at her home. A couple of months from now, we will be back for more adventure. And more stewardship.