Regarding Joy

Mrs. Sofia Cuddeback

Not long ago, a friend of mine called and asked if I would speak to a group of people on the topic of joy. “What is joy?” my friend asked. Is it a choice? A gift? A feeling?

Usually in such a situation, my sanguine and irresponsible self quickly responds “Sure, I’ll give a talk for you!” But this time I paused. I’ve got nothing for you, I thought. Explain joy? How can I do that when I haven’t even figured it out myself?

But I realized that my initial response was perhaps a bit grim. Joy is something we often discuss — or try to discuss — and if we really don’t understand it, we need to face the challenge and not shy away from the questions. What is joy? Is it something we can work toward and thus choose, or is it something that we just have to wait for until it is dropped in our laps? Is it something we feel, or is it a conviction effected through an act of will?

Most of us are not really sure what the word “joy” even means, yet we are certain we need more of it. I pondered on this, and eventually I agreed to give the talk my friend had requested. And I’ve continued pondering ever since. Here follow some ideas on how we might think about and, when called on, speak about this thing called joy.

What is Joy?

Two sets of alternatives come to mind when considering joy. First, we ask: is joy achieved — is it something we acquire on our own — or is it a gift? I think that deep down, we all want to hear that it’s an achievement, because then it is in our power to get more of it. To hear that it is a gift — while this sounds lovely in one way — is quite a bit scarier, since whether a gift will be given to us (or not) is outside of our control. I really want joy, and thus I find myself hoping that it is not merely a gift: what if, for some reason or another, the Giver says “no?”

Two sets of alternatives come to mind when considering joy. First, we ask: is joy achieved — is it something we acquire on our own — or is it a gift? I think that deep down, we all want to hear that it’s an achievement, because then it is in our power to get more of it. To hear that it is a gift — while this sounds lovely in one way — is quite a bit scarier, since whether a gift will be given to us (or not) is outside of our control. I really want joy, and thus I find myself hoping that it is not merely a gift: what if, for some reason or another, the Giver says “no?”

Second, we ask: is joy a conviction or an emotion? To think that it may be an emotion is a bit distressing, because we know that feelings are often fleeting and volatile, and what we really want from joy is something secure and dependable. If joy is a conviction, on the other hand, then we are in charge of joy’s comings and goings. It would be a matter of our will, our choice. So that sounds a bit better. But alas, in reality, we sense that joy is in fact something that cannot be merely an intellectual conviction or a choice of the will; it is something that should also be felt affectively, through emotion.

It seems, then, that joy must be a mixture of all of the above. While it is a gift, there is definitely also a choice to be made in the receiving of it, and we can take action to pursue it. Furthermore, it is in part the result of an intellectual conviction or an act of the will, but it also clearly manifests itself in the emotions as a feeling. How can we possibly hope to understand in practical terms something that is so multifaceted?

Joy and the Appetites

As the wife of a philosopher, the daughter of a philosopher, the sister of two more philosophers, and the sister-in-law of yet another philosopher, my instinct is to approach the question of joy philosophically. Not being a philosopher, but definitely knowing where to find one, I asked my husband, John, to give me a definition of joy developed from both the ancients and Thomas Aquinas. This is the definition he gave me:

“Joy is the resting of the intellectual appetite (the will) in some present good.”

I hate to say it, but that doesn’t sound particularly inspiring. Nor is it even very intelligible at first glance. Fortunately, this definition is actually much simpler than it sounds.

First, Aquinas says that joy is “a resting of the intellectual appetite.” By “appetite” all he really means is anything that hungers for or reaches out for something and is satiated when it gets that thing. There are two main kinds of appetites. The first is bodily appetite, which reaches out for things that are good for us (or that we perceive as good for us) in the realm of the body. Examples are our appetites for food when we are hungry or sleep when we are tired, for that piece of cake or second cup of coffee, or for a frozen custard from the local drive-through because, after all, how often do I not have the kids in the car and can actually buy just one ice cream and enjoy it by myself?

When we get whatever it is that our bodily appetite reaches for, we call that experience delight. You can infer from these examples and from your own experience that the delights belonging to the bodily appetite are quite transient; when the cookies are gone they no longer delight us, except maybe for just a little while in our memory. We do not rest in these goods for long, if we rest in them at all. Delight is not a bad thing — not at all — but it has significant limitations.

We also have an intellectual appetite, which reaches out for goods that we grasp through intellect. Some examples of the intellectual appetite are the desire for justice, the appreciation of the beauty in sacrifice, and the admiration of the virtues of a particular friend. When we acquire the object of our intellectual appetite and rest in it — when we let ourselves be mindful of it and sit within it, metaphorically speaking — that is called joy.

When we acquire the object of our intellectual appetite and rest in it — when we let ourselves be mindful of it and sit within it, metaphorically speaking — that is called joy.

Joy is what we experience when we rest in something that is good and that we love. It is different from the fleeting, sense-based delight that we experience when we drink a glass of water on a hot day or slip our tired feet into soft socks on a chilly evening. Indeed, because the intellectual appetite is not limited by the senses, we can even have joy when the good we love is not physically present. We can experience joy merely from resting in the knowledge of the thing loved. For example, just thinking of a good friend who is not with me can bring me joy, even though I cannot in this moment have his or her presence. And the joy that comes from resting in intellectual goods is more enduring than the delights of the bodily appetite. While the delight I feel when eating a piece of pie is a lovely thing, the joy I feel when I sit at the dinner table and rest in the goodness of being with my family as we eat the pie is much deeper and more lasting.

Resting in Joy

It should not surprise us if we often confuse delight and joy. Sometimes, when we are hoping to increase joy we are actually pursuing bodily pleasures, which are transient — we are simply pursuing delight. This is not where we find joy. This can lead not just to bad habits (eating too much chocolate, for example, because we hope lasting joy will come from this instead of fleeting delight), but also to discouragement and despair (such as when you find present-opening on Christmas or a birthday empty and disappointing, and wonder what is wrong with you that you are not feeling joy). We need to follow the intellectual appetite, under the guidance of reason, to achieve true joy.

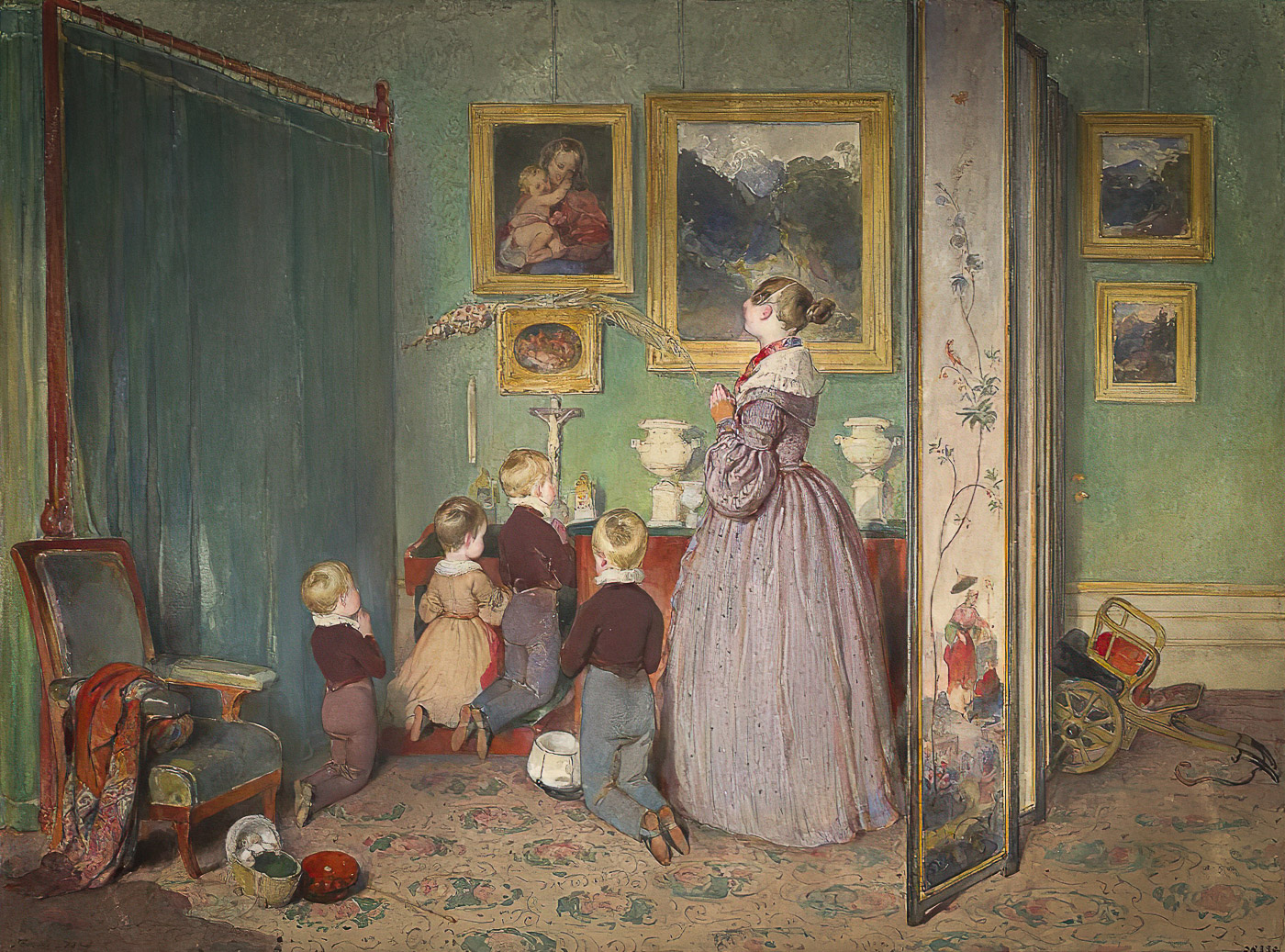

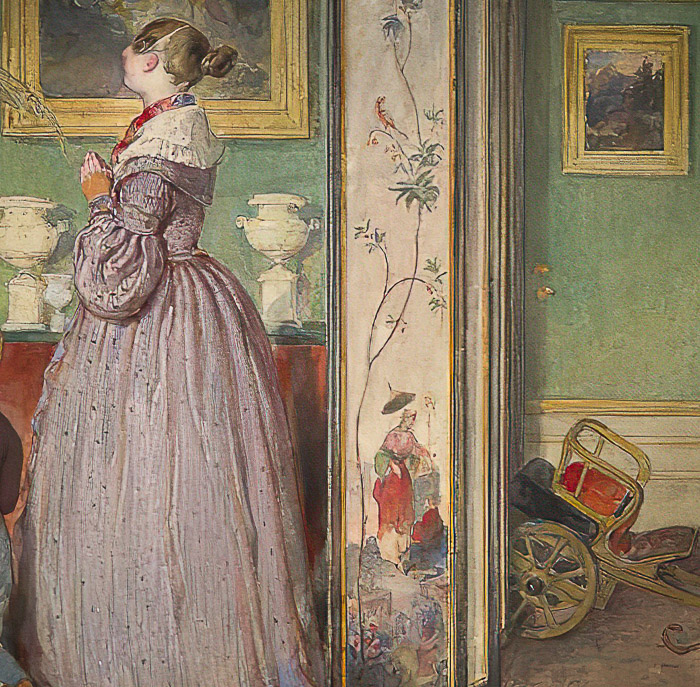

Further, joy is not merely the result of achieving or possessing a good. Rather, the essence of joy is in resting in that good. Resting means allowing ourselves to fully note and experience the good, rather than ticking it off our list as some sort of accomplishment and then moving immediately to the next thing. Joy is not achieved; it is experienced through resting in the good that is at hand. If we are distracted from the thing that we love, however, going on to the next pursuit instead, then we are no longer resting in that good. We have lost the joy proper to that good. For example, if a mother has pursued the good of a family bonding at dinnertime by preparing a lovely meal, but then she jumps up to do the dishes instead of joining in the conversation, then she has not rested in the good of this family togetherness, and so she is unlikely to experience joy. The dishes can wait long enough for her to experience the good fruit of family communion! Likewise, the perfect building of a chicken coop can give way here and there to make room for Dad to rest in the good found in his children working with him (even if their “help” means the coop doesn’t end up quite plumb).

Further, joy is not merely the result of achieving or possessing a good. Rather, the essence of joy is in resting in that good. Resting means allowing ourselves to fully note and experience the good, rather than ticking it off our list as some sort of accomplishment and then moving immediately to the next thing. Joy is not achieved; it is experienced through resting in the good that is at hand. If we are distracted from the thing that we love, however, going on to the next pursuit instead, then we are no longer resting in that good. We have lost the joy proper to that good. For example, if a mother has pursued the good of a family bonding at dinnertime by preparing a lovely meal, but then she jumps up to do the dishes instead of joining in the conversation, then she has not rested in the good of this family togetherness, and so she is unlikely to experience joy. The dishes can wait long enough for her to experience the good fruit of family communion! Likewise, the perfect building of a chicken coop can give way here and there to make room for Dad to rest in the good found in his children working with him (even if their “help” means the coop doesn’t end up quite plumb).

Moreover, the broader or greater a certain good, and the more universal its goodness, the less likely we are to be distracted from resting in it, and so our joy in that rest will be more abiding. Let’s say that you love hiking: you experience the goods of fresh air, physical exercise, the grandeur of God’s creation and perhaps even the bond that these things create between you and the people with whom you are hiking. Resting in the good of hiking, being present and aware within the experience of that good, gives you joy. But there are other goods that you desire (and indeed, need) that hiking does not fulfill; you cannot rest there for long. Soon, you must turn away to something else, which places a natural limit on the joy of hiking. A tremendous good like the birth of your child, however, can carry you in joy for days or even weeks before your attention is fully turned to another good.

So there are some things that bring deeper, longer, greater joy than others.

Finding Joy in God’s Love

When we understand that different goods yield different degrees of joy, we can start to see how the love of God, the greatest of goods, is also that which will provide the most abiding rest and the longest, deepest joy. Here we may just begin to grasp how so many saints could manage to be joyful even when undergoing great physical or emotional pain.

How do we do this, though? How do we rest in God’s love and thus experience more abiding joy? One place to start is thinking about what it means to “love all things in God.” There are many objects, goods, and people that we love, but our emotions are fickle and our commitments are often tested. God is not fickle, nor is his love fragile. If we can come to appreciate that all other goods are in some way facets or reflections of God’s love and goodness, then even as we move from one thing to another seeking the goods we need and seeking love in this life, we may remain at rest in his overwhelming goodness. If God’s love is the continual stream in which all other goods ebb and flow, then when we rest within that stream we may find abiding joy.

Thomas Aquinas tells us that “the perfection of joy is peace,” and St. Paul tells us that both joy and peace are fruits of the Holy Spirit: “[T]he fruit of the Holy Spirit is love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness and self control.” In light of the relationship between love and joy —that joy comes from resting in some good that we love — perhaps this list is not only an enumeration of fruits but an ordered list of causes. When we love something, when we possess it and rest in it, we have joy; and when we remain in that joy by focusing on the greatest of goods, our God, then we have peace. The rest of the list seems to follow in the same causal way.

Thus it also seems the case that joy is indeed at least partly a gift. It is the gift of resting in the thing loved, something that we can affect somewhat by our attitude, attention, and will but that also comes forth from the mere existence of love. We can’t fabricate joy.

Forming the Appetites

We can’t fabricate joy, but there are things we can do to increase it. We can, for example, make a commitment to rest in the goods we experience rather than moving directly on to the next pursuit. We can work on our understanding — our ability to see and rest more fully in the true good. We can focus on seeing each good within the stream of God’s great love, resting in that good continuously even while we only briefly rest in lesser goods and even encounter temptation and other evils. And we can also work on forming our appetite to actually want that which provides the most abiding joy. Our appetite moves toward what we know, see, and experience: when we see something that is good, when we understand its goodness, we begin to want it. And so appetite is indeed changeable. Suppose a child doesn’t love a particular food — mushrooms, let’s say. This is often because he doesn’t yet understand what happens to them in a frying pan with butter, salt, and a little marsala wine. He resists getting to know them through experience. But with more exposure of the right kind, in time he may stop reflexively saying “Yuck!” and instead come to love the food for the wonderful thing it is.

So if “resting in God’s love” sounds a bit far-off and even bland to you — not quite as appealing as sitting on the beach with a good book, for example — don’t worry. You can, in fact, change what you want by forming your intellect to create better appetites. Indeed, we can make a plan for forming our own appetites, or we can let the world do that work for us (likely greatly to our detriment), as it is constantly trying to do. If we are seeking true joy, it is far better for us to pay attention to forming our own intellects properly so that our appetites desire the things that are truly good.

If we are seeking true joy, it is far better for us to pay attention to forming our own intellects properly so that our appetites desire the things that are truly good.

We can do this in many ways but primarily by occupying our minds with “whatever is true, whatever is noble, whatever is right, whatever is pure, whatever is lovely, whatever is admirable.” Regular reading of sacred scripture immerses the intellect in truths about human nature, hierarchies of goods, and beautiful language and examples, forming the appetite to love and seek goodness. The Psalms have been a favorite for this sort of immersive formation of the appetites for centuries upon centuries. In fact, they also play a central role in another enduring form of regular prayer, the Liturgy of the Hours, which remains an amazing tool for forming the intellect and imagination in a consistent and rhythmic way. Most of us aren’t monks, of course, for whom the Hours were originally created, and so we can’t all pray all the Hours or even pray one of them in full. But my husband and I love to draw on these prayers with our family each morning as we try to begin our day conforming our appetites to that which is truly good.

Beyond prayer, we can also seek to notice what is good and beautiful in all aspects of our lives, to surround ourselves with beauty and goodness to the degree we can, and to look for the reflections of God’s goodness all around us. This means not just things that are good to the senses or the body (although these can be important), but also those things that are intellectually good. We can read good stories, try to notice small acts of kindness, and practice taking deep breaths instead of blowing our tops. The more we turn our habits toward such actions and fill our environments with such things, the more our appetites will seek new (or better) goods, and the more we will begin to experience authentic joy.

So let us not lose hope when, in the throes of spring cleaning, we’re decluttering our homes and find that almost nothing there “sparks joy” in the true sense of the word. We can take delight in the sense pleasures of life, which are by and large good things of which we should be glad. But when we are seeking joy, we will need to look beyond what was in our Christmas presents a few months back and remember that delight cannot do the work of joy. It is not the toy or book or cashmere sweater in the gift box that will bring joy, although we can revel in such delights. Instead, it is resting in the love of the person who gave us the gift in the first place, and in trusting in the great love of Christ above all.