Integrity & Beauty

A Wandering Review of

A Sand County Almanac

Dr. Jeff Gardner

In the early twentieth century, the United States underwent a profound transformation. Millions of people migrated out of the countryside and packed themselves into cities. By the early 1920s, nearly eleven million people had left rural America and were fighting for a place in booming urban areas such as Orlando, New Orlean, and Los Angeles. By 1925, for the first time in the history of the nation, more Americans lived in cities than in the country.

Aldo Leopold, a young conservationist, worried about the torrent of folks chasing the promise of a better life in factories and office buildings. While he understood that people had to make a living, he believed that America’s growing disconnection from the land did not come without a cost.

“There are two spiritual dangers in not owning a farm,” Leopold wrote in the 1930s. “One is the danger of supposing that breakfast comes from the grocery, and the other is that heat comes from the furnace.”

To blunt these risks, Leopold recommended that everyone garden something edible, no matter how small the patch. And they should eat whatever came up, with no shopping for substitutes, please. As to the second danger: learn to split wood and build a fire that could warm the house, especially when a February blizzard rages outside.

Born in Iowa in 1887, Aldo Leopold is still regarded as America’s foremost conservationist. From humble, Mark Twain-like beginnings, Leopold rose to be a leading voice of twentieth-century American conservationism.

Aldo Leopold was born and raised in a tight-knit and prosperous, Midwestern German immigrant community. His father and mother were first cousins, and Aldo grew up speaking German until he started school and needed to learn English.

Though Aldo was a studious and well-behaved child in the classroom, his passion was the outdoors. A born naturalist, Aldo would, by his own account, neglect bodily concerns (including eating and washing) and spend as much time as he could exploring the bluffs and grasslands around Burlington, Iowa.  By age ten, Leopold was building rafts and floating the Mississippi River, docking at densely wooded areas where he would spend hours observing and cataloging the many bird species that call the delta home. In the summers, his father Carl and his mother Clara would pack Aldo and his three siblings into the family car and make the long drive to Michigan’s upper peninsula and out to Marquette Island, escaping the heat of the Midwest and enjoying the cool wilds of lake Huron.

By age ten, Leopold was building rafts and floating the Mississippi River, docking at densely wooded areas where he would spend hours observing and cataloging the many bird species that call the delta home. In the summers, his father Carl and his mother Clara would pack Aldo and his three siblings into the family car and make the long drive to Michigan’s upper peninsula and out to Marquette Island, escaping the heat of the Midwest and enjoying the cool wilds of lake Huron.

Exceptionally intelligent, Leopold excelled in academics. In 1904, when he was not yet seventeen, he left Iowa for New Jersey where he enrolled in preparatory school and then Yale’s newly established forestry program. Aldo Leopold completed his undergraduate and master’s degree in just four years.

By 1909, Leopold was working as an assistant ranger for the U.S. Forest Service in the Arizona and New Mexico territories. One of his early duties was to eliminate so-called “nuisance predators,” bears, wolves and mountain lions. Predator control, pushed by ranchers throughout the West, was an official U.S. Forest Service policy that assumed that fewer apex carnivores meant more deer, elk, and cattle.

Beyond controlling predators on federal lands leased for grazing, the U.S. government pursued this policy in national parks. It may come as a surprise to most, but national parks such as Yellowstone, which was established in 1872, were created as tourist attractions and not as wildlife sanctuaries. And just like going to the zoo, visitors expected to see big, beautiful animals such as elk and moose when they visited the park. Thus, in the early twentieth century, U.S. Forest Service game management policy ran something like this: if there are no predators to kill the big game then there will be more big game for park tourists to see. As a result of this policy, the wolf was eradicated from Yellowstone National Park by 1926.

In the early 1920s, Aldo Leopold and a group of friends were hunting in the Arizona/New Mexico territory when they spotted a mother wolf and half-dozen pups at the bottom of a ridge. Since, Leopold recalled, no one would dream of passing on an opportunity to kill a wolf, he and his party began firing at the pack “with more excitement than accuracy.” Some wolves were killed outright, but others were only wounded, including the mother, which lay panting and bleeding at the bottom of a hill. Rushing down to finish what he had started, Leopold was confronted by the spectacle of the dying mother wolf. He reached her in time, he wrote, “to watch a fierce green fire dying in her eyes.” At that movement, looking at the sad, pain-wracked figure of the magnificent creature that he had mortally wounded, Aldo Leopold had a gut-wrenching epiphany: despite (or perhaps because of) all his university education, there was something that the wolf and the mountain knew about wilderness and nature that he did not. He had been certain, as he related in an essay titled “Thinking Like a Mountain,” that “fewer wolves meant more deer,” which was a good thing, especially for hunters. But the mountain, he realized, after it was over-grazed by too many deer and stripped bare by erosion, did not agree with him. Aldo Leopold grasped that when it came to our relationship with the land, he and all the rest of us needed a serious rethink.

[D]espite (or perhaps because of) all his university education, there was something that the wolf and the mountain knew about wilderness and nature that he did not.

Though Leopold would continue to hunt throughout his life (he preferred bow and arrow, thinking it more sporting), his time in the Arizona/New Mexico territory was a watershed moment. He understood that rapid industrialization, aggressive predator elimination, and the plowing under of thousands of acres of land were erasing, in the span of less than one generation, wilderness from the American landscape. “Like winds and sunsets,” Leopold would later write, “wild things were taken for granted until progress began to do away with them.”

Drawing on these realizations, Leopold began to formulate a new and uniquely American land ethic, which held that “the opportunity to see geese is more important than television” and “the chance to find a pasque-flower is a right as inalienable as free speech.”

Aldo Leopold realized that he would not be able to fully articulate his new ethic nor put it fully into action while working as a forest ranger. He needed a different stage and sought a transfer that would afford him the time and audience to bring his vision to fruition.

By 1924 Leopold transferred to the U.S. Forest Products Laboratory in Madison, Wisconsin, where he became its associate director. Within a decade, Leopold had carved out an appointment as Professor of Game Management in the University of Wisconsin’s Agricultural Economics Department, a first of its kind in the United States.

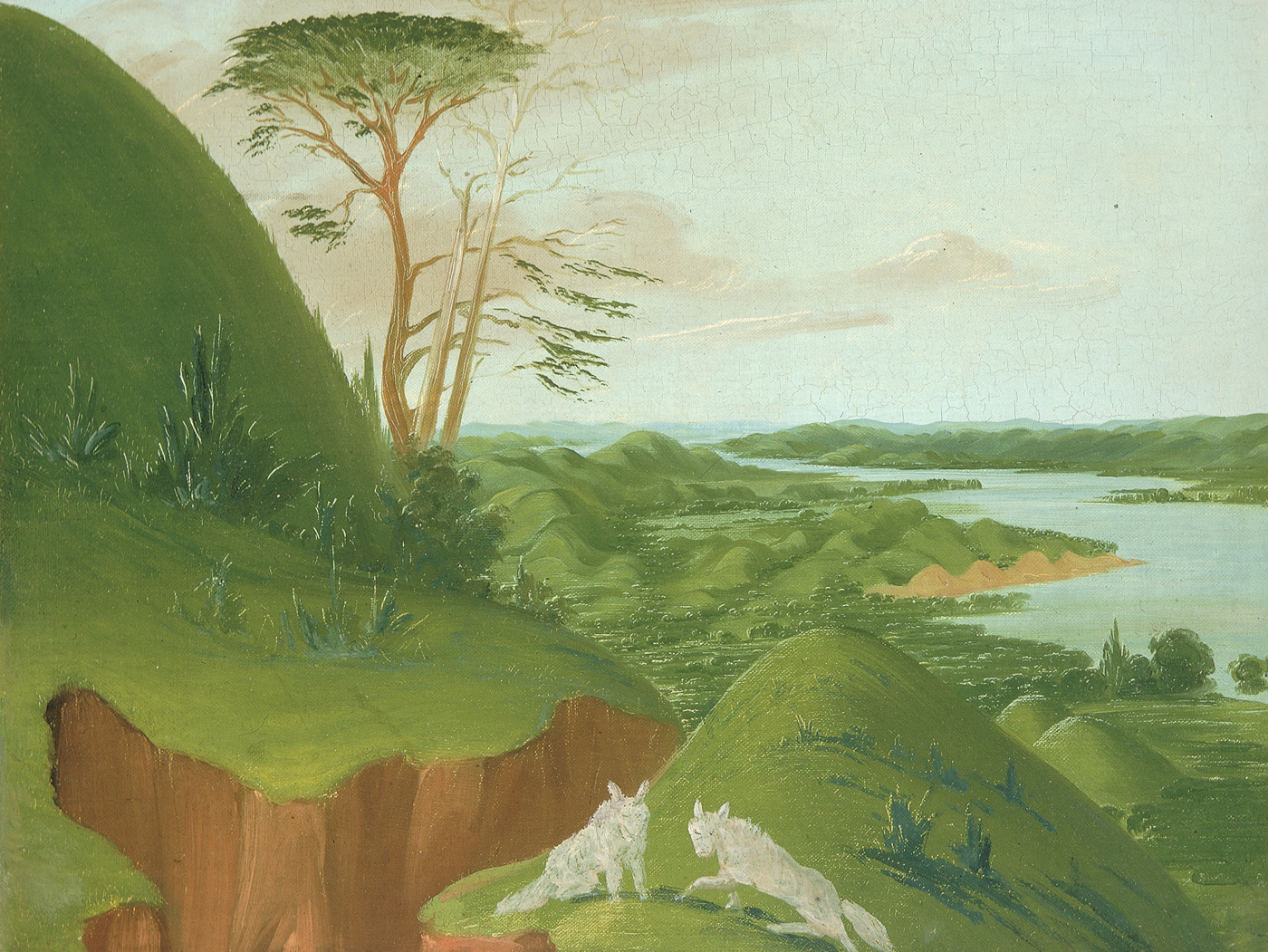

In his new role as teacher, Leopold began to write about and live out his vision of a workable conservationist ethic, purchasing some one hundred acres of land near Baraboo, Wisconsin, in the central sandy plains of the state.  Since the late 1870s, that region of the state had been over-logged and over-grazed, leaving the soil exhausted and the landscape barren. Leopold set about transforming an old chicken coup on the property into a cabin for his family, and together, working weekends and holidays, they began to replant and rewild the land. Leopold chronicled his family’s time on the land in a series of essays that form the heart of A Sand County Almanac.

Since the late 1870s, that region of the state had been over-logged and over-grazed, leaving the soil exhausted and the landscape barren. Leopold set about transforming an old chicken coup on the property into a cabin for his family, and together, working weekends and holidays, they began to replant and rewild the land. Leopold chronicled his family’s time on the land in a series of essays that form the heart of A Sand County Almanac.

Leopold’s book, A Sand County Almanac, was published posthumously and may not have been planned by the author as a single book. Instead, the work is a collection of stories and reflections, which, taken together, form an invitation to reconsider how we relate to the land and how we ought to interact with it.

In the book, Leopold acknowledges that while we are subjected to the force of nature, with ashes to ashes and dust to dust, our technology blunts our awareness of this connection. Technology’s ability to separate us from the forces of the natural world, Leopold notes, is not a bad thing, but this separation can be detrimental to our well-being. “This much is crystal-clear,” Leopold wrote, that “our bigger-and-better society is now like a hypochondriac, so obsessed with its own economic health as to have lost the capacity to remain healthy. . . . Nothing could be more salutary at this stage than a little healthy contempt for a plethora of material blessings.”

A Sand County Almanac is organized into three parts, with parts one and two composed of a collection of essays and meditations on time spent watching the ebb and flow of the natural world. Part three, titled “The Upshot,” is a philosophical, sometimes even academic, consideration of land usage and Leopold’s own brand of conservationism. Though less lyrical than parts one and two, “The Upshot” is nonetheless well worth reading.

Anyone old enough to remember the Farmers’ Almanac will recognize the structure and rhythm of part one of A Sand County Almanac. The chapters are named after the months and take us through the work and reflections of Leopold and his family as they restored over one hundred acres of land near Baraboo, Wisconsin, and the shack they built on it.

For example, January, Leopold wrote, is a time for reflection, for following a skunk’s tracks in the snow and wondering where he might be going. Or for looking, carefully and quietly, at “what young pines the deer have browsed.” May is for the arrival of the plover, a winged timepiece that signals the return of the dandelions to the Wisconsin prairie. You will know it is November, Leopold suggests, when you hear the wind making music in the dried corn stocks, with their loose husks swirling skyward. And overhead you can hear the faint honk of the Canadian goose, hurrying south and sounding out the taps for the dying fall. Many of the stories in part one of “A Sand County Almanac” don’t “go” anywhere, but that is exactly the point.

May is for the arrival of the plover, a winged timepiece that signals the return of the dandelions to the Wisconsin prairie.

Part two, titled “Sketches Here and There,” is a selection of some of the eight hundred articles and reflections that Leopold wrote over the arc of his lifetime. Unlike part one, “Sketches” does not walk the reader through the seasons but offers ways of seeing our interlocking relationship to a wider, wilder world. Most essays are short, with a Readers’ Digest-of-old feel, taking only five minutes to complete, but with enough weight to linger on the mind all day. Of these essays, the most well-known is “Thinking like a Mountain,” the very same in which Leopold related the story of killing the mother wolf.

The death of such a beautiful animal as a wolf notwithstanding, this story is perhaps the most sublime of “Sketches.” Summarizing the large lesson drawn from watching the dying wolf, Leopold wrote: “I now suspect that just as a deer herd lives in mortal fear of its wolves, so does a mountain live in mortal fear of its deer. And perhaps with better cause, for while a buck pulled down by wolves can be replaced in two or three years, a range pulled down by too many deer may fail of replacement in as many decades.”

Like an exercise in the negative, “Thinking like a Mountain” and many of the “Sketches” cautions the reader to bear in mind that just because we can do something does not mean we should. Perhaps too much safety, Leopold reflects, “yields only danger in the long run.”

In the third and final part of A Sand County Almanac, “The Upshot,” Leopold articulates a conservation ethos that may sound unfamiliar to the twenty-first-century reader. Leopold acknowledges the need to extract resources from the land. He advocates hunting and reflects that some of his first and most vivid memories of land and landscape were formed while hunting rabbit and duck as a young boy. Leopold was not an ecological segregationist, and one will not find the “hands-off, stay-out” approach to nature that dominates our environmentalist landscape. What’s good for the land, he notes in “The Upshot,” is what’s good for us, and our separation from the land is not good for either.

In the third and final part of A Sand County Almanac, “The Upshot,” Leopold articulates a conservation ethos that may sound unfamiliar to the twenty-first-century reader. Leopold acknowledges the need to extract resources from the land. He advocates hunting and reflects that some of his first and most vivid memories of land and landscape were formed while hunting rabbit and duck as a young boy. Leopold was not an ecological segregationist, and one will not find the “hands-off, stay-out” approach to nature that dominates our environmentalist landscape. What’s good for the land, he notes in “The Upshot,” is what’s good for us, and our separation from the land is not good for either.

Taken as a whole, A Sand County Almanac is more than a collection of short, pleasing stories about birds and squirrels. It is a gentle suggestion that the remedy to what ales us is, quite literally, right in front of us — the natural word. But bogged down and bored stiff by an ever-expanding universe of technology, Leopold suggests, we have been drawn away from a healthy relationship with the land and into a deadly illusion: we have come to believe that we are technology’s master but fail to see that we are, in plain fact, its slaves. Breaking these chains, he proposes, is as simple as spending time in the same natural places that make our time on this earth possible.

The most enjoyable aspect of A Sand County Almanac is not one story or another but its overall tone. True, Aldo Leopold has a point he wants to make, maybe even an axe to grind. But like a wise and patient father speaking with his child, the book is not a sermon, but a nudge, a proposition that maybe, just maybe, a thing or an action is right when it tends to preserve integrity and beauty, and wrong when it intends otherwise.