The Long Advent of 1940

and the

Scandal of the Incarnation

A Review of Bariona

Dr. Ryan Hanning

During the arduous Advent of 1940, a motley crew of French and Belgian intelligentsia along with a few Jesuit priests prepared a Nativity play for their fellow captives and their German captors at the POW camp in Trier, Germany. In the penultimate scene of the play, the narrator beckons towards the unlikely tableau of a God born man.

“[T]he mountain is swarming with people on holiday and the wind carries the echo of their joy up to the top of the crest. I shall take advantage of this pause to show you Christ in the stable, so you don’t see it some other way . . .. Here it is. Here is the Virgin and here is Joseph and here is the baby Jesus. The artist has put all his love into this sketch but you may find it a little naïf perhaps. Look, the characters have fine ornaments but they’re stiff: you’d take them for puppets. They certainly weren’t like that. If you were like me, eyes closed . . .. But listen: you only have to close your eyes to hear me and I’ll tell you how I see them inside me. The Virgin is pale and looking at the child. What should be painted on her face is an anxious amazement that has only appeared once on a human face. Because the Christ is her child, flesh of her flesh, it is the fruit of her womb. She has carried him nine months, and she will give him her breast, and her milk will become the blood of God. And at certain moments the temptation is so strong that she forgets he is God. She hugs him in her arms and says: my little one! But in other moments, she is speechless and thinks: God is there and she feels gripped by a religious horror for this mute God, for this terrifying child. For all mothers are in this way attracted at moments before this rebellious fragment of their flesh that is their child and they feel outcast before this new life that has been made of their life and that they populate with foreign thoughts. But no child has been more cruelly and more quickly torn from his mother, for he is God and is beyond everything that she can imagine. And it is a hard trial for a mother to be ashamed of herself and of her human condition in front of her son. But I think there are also other moments, swift and difficult, in which she feels at the same moment that the Christ is his son, and that he is God. She looks at him and thinks: «This God is my son. This divine flesh is my flesh. He is made of me, he has my eyes and the shape of his mouth is the shape of mine. He looks like me. He is God and he looks like me». And no woman has had in lot her God to herself alone. A little God that one can take in one’s arms and cover with kisses, a warm God that smiles and breathes, a God that one can touch and that lives. And it is in those moments that I would paint Mary, if I were a painter, and I would try to render the expression of tender boldness and timidity with which she reaches out her finger to touch the sweet small skin of this child-God whose warm weight she feels in her lap and who smiles at her.”

"A little God that one can take in one's arms and cover with kisses, a warm God that smiles and breathes, a God that one can touch and that lives."

This poetic vision and theologically rich prose were not written by the priests, nor the other Christian philosophers and theologians held captive in the wooden dorms of Stalag XII D. Rather, they were penned by the existentialist, nihilist, and atheist Jean-Paul Sartre. Perhaps at this point some background is in order.

On the first day of September, 1939, Germany invaded Poland. Within forty-eight hours, France and the United Kingdom declared war on Germany. In a small room at the Lycée Pasteur in Paris, Jean-Paul Sartre received the news with a sober resignation; the world was at war. A year earlier Sartre was introduced to the literary world with the success of his impious and unapologetically existential novel “La Nausee.” He was teaching, writing, and developing his own philosophical insights into existence, and the radical independence of consciousness and freedom. It was in this setting that Sartre’s promising career was interrupted by the war.

He wrote openly against totalitarianism and its opposition to human freedom. He later reflected on the galvanizing force of the conflict, beginning his 1944 article in the Atlantic with the paradox: “Never were we freer than under the German occupation. We had lost all our rights, and first of all our right to speak. They insulted us to our faces. . .. They deported us en masse. . .. And because of all this we were free . . . the Resistance was a true democracy; for the soldier, as for his superior, the same danger, the same loneliness, the same responsibility, the same absolute freedom within the discipline.” Sarte was drafted into the French Army as a meteorologist and a short time later was captured by the Germans. In June 1940 he was sent to Trier where, despite his confinement, he enjoyed the company of priests, professors, and a small collection of books including a Bible, Bernanos’ Diary of a Country Priest, and Heidegger’s magnum opus Being and Time.

Sartre became friends with Abbé Marius Perrin and the other priests, and according to those interred with him in Triers, felt a brotherhood with the priests, especially the Jesuits, despite frequent debates regarding faith. One of the priests, Father Boisselot, had secured favor with the camp commander and regularly used his barracks to celebrate Mass for the captives and soldiers alike. It was Father Boisselot’s idea to host a Nativity play for the camp. They agreed that Sartre, being the only published novelist of acclaim in the camp, should be tasked to write the play. He agreed provided that he could be fiercely authentic to the task.

For weeks Sartre re-engaged the gospel of his youth. But he did so as an existentialist, holding fast to the idea that we are particular individuals with no shared essential qualities other than our freedom; as a nihilist who found no perceptible meaning in the random patterns of life; and as an atheist who rejected the existence of God, but admittedly sought to secure his own salvation. Ultimately he approached it as a devout anti-Christian, though he could never escape the weight of Christian philosophy or culture. Saying in his autobiography, “Removed from Catholicism, the sacred was deposited in belles-lettres and the penman appeared, an ersatz of the Christian I was unable to be, my sole concern was salvation. . .. I thought I was devoting myself to literature, whereas I was actually taking Holy Orders. . .. I grew like a weed on the compost of Catholicity; my roots sucked up its juices and I changed them into sap.”

"I grew like a weed on the compost of Catholicity; my roots sucked up its juices and I changed them into sap."

It was with this abandonment of any sense of the sacred, objective, or real, that Sartre dove into the mystery of the incarnation as the ultimate paradox of freedom — that God, who is by definition, totally free, would give himself to us.

Bariona – Sons of Thunder: A Brief Summary

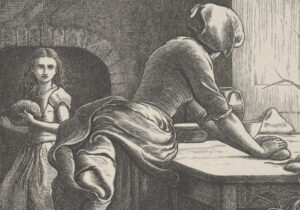

The play is set in the town of Bethaur not far from Bethlehem a few days before Jesus’ birth. The town leader, Bariona is an heirless leader who has resigned himself to the fact that their village is dying. No youth inhabit its homes, and the Romans are taxing them beyond their limits. Bariona swears an oath, “no more children.” They will resign themselves to their inevitable death and in doing so, will still exercise their noble freedom and the satisfaction of giving the Romans nothing. After having sworn the pact with the other men in the village, his wife Sarah announces to Bariona that she is expecting and that he has lost the hope that she and others need to celebrate the gift of new life. “You just put a curse on me: you put a curse on my womb and the fruit of my womb!” In an act of deviance she swears that she will have this child, and love it, and give it to the world regardless of the circumstances it will face. The plotline is set. Bariona has lost hope, Sarah has discovered it.

While Bariona seeks the “witch-doctor” for the bitter herbs that will kill his child, shepherds nearby encounter a distracted divine stranger who has come to share the good news.

ANGEL: Oh, yes: the message: Here it is: wake your brothers and get going. You will go to Bethaur and you will tell everyone the good news…it’s in Bethlehem, in a stable. Just hold on a minute and be still. There’s a great void and a great expectancy in heaven, because nothing had happened yet. And there’s this cold in my body like the cold in heaven. Right this minute there is a woman lying on straw in a stable.  Be still, because heaven has become completely empty like a great big hold; it’s empty and the angels are cold. Ah! Are they cold!” A long silence. “There. He’s born! His infinite and sacred spirit is imprisoned in the soiled body of a child, and is astonished to be suffering and ignorant. That’s it: our Master is no longer anything but a child. A child who can’t speak. I’m cold. Lord; how cold I am. But that’s enough weeping about the angels’ sorrow and the immense emptiness in the heavens. On earth, mild odors are darting everywhere, and it’s the turn of human beings to rejoice…go down in a throng into the city of David to worship Christ, your savior. And this shall be a sign unto you; you shall find the babe wrapped in swaddling clothes, lying in a manger. Go find Bariona who is suffering and whose heart is full of gall and say to him, “Peace on earth to men of good will.”

Be still, because heaven has become completely empty like a great big hold; it’s empty and the angels are cold. Ah! Are they cold!” A long silence. “There. He’s born! His infinite and sacred spirit is imprisoned in the soiled body of a child, and is astonished to be suffering and ignorant. That’s it: our Master is no longer anything but a child. A child who can’t speak. I’m cold. Lord; how cold I am. But that’s enough weeping about the angels’ sorrow and the immense emptiness in the heavens. On earth, mild odors are darting everywhere, and it’s the turn of human beings to rejoice…go down in a throng into the city of David to worship Christ, your savior. And this shall be a sign unto you; you shall find the babe wrapped in swaddling clothes, lying in a manger. Go find Bariona who is suffering and whose heart is full of gall and say to him, “Peace on earth to men of good will.”

The shepherds report to Bariona what they have seen and heard. As Bariona skeptically listens, wise men enter into Bethaur confirming the news. The very elders who had resigned themselves to die earlier in the evening were now filled with hope, and the village of Bethaur prepared to go and worship the newborn King. That is, everyone but Bariona.

BARIONA: I don’t believe in the Messiah any more than I believe any of your jive. You rich people, you kings, I see through your game. People of Bethaur, I don’t want to be your leader anymore, because you doubted me. But I’m telling you again for the last time, look your misfortune squarely in the eye, because man’s dignity lies in his despair.

BALTHAZAR: Are you sure it doesn’t lie in his hope instead? I can see from your face you’ve suffered and I can also see that you’ve enjoyed it. Your features are noble but your eyes are half-closed and your ears seem stopped up. You’re blind & deaf to human speech, & won’t listen to any advice except what comes from your own pride. But look at us, we’ve suffered too, and among men we’re wise. But when that new star rose, we didn’t hesitate to leave our kingdoms and follow it, and we are going to worship our Messiah.

BARIONA: Well go ahead and worship him. Who’s stopping you, and what’s that got to do with me?

BALTHAZAR: You’re suffering Bariona.

You are suffering, and yet your duty is to hope. Your duty as a man. It’s for you that Christ came down to earth, for you more than for anyone, because you’re suffering more than anyone. An angel doesn’t hope at all, because he has his joy & God gave him everything ahead of time. And a stone doesn’t hope either, because it lives dully in a perpetual present. But when God created human nature, he joined hope and care together. A man, you see, is always much more than he is. You look at this man here, he’s there. And that’s not true: Wherever a man happens to be Bariona, he’s always somewhere else. Somewhere else, beyond the purple mountaintops you see from here. In Jerusalem, in Rome, beyond this icy day. Tomorrow. And all that future which man is shaped by-all those mountaintops, all those purple horizons, all those wonderful towns-all of that is hope. Hope. Look at these prisoners all around you here, living in the mud & cold. Do you know what you’d see if you could follow their souls? Rolling hills, a softly winding river, cornfields, and the southern sun. That’s where they are; down there. And for a prisoner who’s shivering with cold & crawling with bugs & rats, the green fields of summer are hope. Hope & what’s best in them. And what you want to do is take away their summertime and fields and sunlight on those far-off hills.

While the others prepare to go and worship, Bariona as well as the Publican who has come to exact taxes consult with the witchdoctor. She reveals to him the destiny of this messiah. He will serve the poor, heal the sick, and perform miracles. But will ultimately face a cruel death. Bariona is enraged. This new messiah would die and leave his followers to the same fate! The plot thickens.

BARIONA: We were expecting a soldier & they sent us a mystical lamb who preaches resignation to us, “Do as I do; die on your cross uncomplainingly and cautiously, so that you won’t upset your neighbors. Think that you have merited your sufferings. And if they seem too great to bear, imagine they are trails which will make you pure. Say Thank you, always say thank you when they slap you, when they kick you. And if you’re good and humble and contrite, then you’ll have a place in the kingdom of the humble people, which is in Heaven…” Is that what my people are to become, a people who go willingly to their own crucifixion? Ah, Romans, if this is true, you won’t have done a quarter of the harm to us that we’re going to do to ourselves. Resignation will kill us; and I hate it Roman, more than I hate you.

LELIUS: Whoa; whoa down there chief, you’ve lost your common sense. And in your wilderness you’re saying things you’ll be sorry for.

BARIONA: Shut up! (To himself) if only I could keep it from happening… Keep the pure flame of rebellion burning in them… Oh my brothers! You’ve abandoned me and I’m not your leader any more. But at least I’ll do this for you. I’ll go down to Bethlehem. The women are slowing them down and I know short cuts they don’t: I’ll be there before they are. And it won’t take long I guess, to destroy this plot.

Sarah and the others go to worship the God born man, while Bariona seeks to take the life of this supposed “King” who will let them down, as everything in this meaningless world is apt to do. He goes ahead of them with murderous intentions.

Arriving before Sarah and the others, he asks a local man (who is really an angel) about the baby.

ANGEL: It’s a son. A beautiful little boy. How much they seem to love him! The mother had scarcely had him before she washed him and took him on her lap. And the man, he isn’t real young anymore, right? He knows that this baby is going to go through all the suffering he’s already been through. And I imagine he must be thinking, maybe he’ll succeed where I tried and failed.

BARIONA: I don’t know. I don’t have a son.

ANGEL: I’m sorry for you. You’ll never have the look, that luminous and slightly comical look, of a man who hangs back, very embarrassed by his big body and sorry he didn’t suffer labor pains for his son.

BARIONA: Who are you? And why are you talking to me this way?

ANGEL: I’m an angel, Bariona. I’m your angel. Don’t kill that baby.

BARIONA: Get out of here.

ANGEL: Yes I’m going. Because we angels can’t do anything to stop human freedom. But think about that look on Joseph’s face.

BARIONA (alone): I’ve had enough of angels! It’s time, because the others will be here soon. And that’s what Bariona’s last great act will be: killing hope. (He opens the door a crack) The woman has her back turned to me and I can’t see the baby; he’s on her lap, I guess. But I can see the man. It’s true: The way he’s looking at her! With such eyes! What can there be behind these two unclouded eyes, unclouded like two empty places in that tangled furrowed face? … All right; I’m beaten. There they are. I don’t want them to recognize me.

[Sarah and the elders arrive to worship and Balthazar finds Bariona at the stable.]

BALTHAZAR: Is that you Bariona? I thought I’d find you here.

BARIONA: I didn’t come to worship your Christ.

BALTHAZAR: No; you came to punish yourself and keep to yourself on the edge of our happy crowd. They’ll betray him the way they betrayed you. Right now they’re showering him with gifts & tenderness, but there’s not one of them, who wouldn’t abandon him if he knew the future. Because he’ll disappoint them all, Bariona. They’re expecting him to run the Romans out and the Romans won’t run out, to put an end to human suffering and people will still be suffering a thousand years from now just the way they are today.

BARIONA: That’s what I told them.

BALTHAZAR: I know. And that’s why I’m speaking to you now, because you’re closer to Christ than all of them and your ears can be opened to receive the real good news.

BARIONA: And what is this good news?

BALTHAZAR: Listen: Christ will suffer in the flesh because he is man. But he is God too and in his divinity he is beyond that suffering. And we men made in the image of God are beyond all our own suffering to the extent that we are like God. Look: until tonight man had his eyes stopped by his suffering. And you Bariona, you too were a man of the old dispensation. You looked upon your suffering with bitterness and said, I’m mortally wounded; and you wanted to lie down on your side and spend the rest of your life meditating the injustice that had been done to you. No Christ came to redeem you; he came to suffer and to show you how to deal with suffering.

Suffering is a common thing, a natural fact, that you ought to accept as if you had it coming to you; and it is unbecoming to talk about it too much, even to yourself. Come to terms with it as soon as possible, snuggle it down nice and warm in the middle of your heart like a god stretched out by the fire. Don’t think anything about it.

Then you will discover that truth which Christ came to teach you and which you already know: you are not your suffering. Whatever you do and however you look at it, you surpass it infinitely; because it means exactly what you want it to. Whether you dwell on it as a mother lies down on the frozen body of her child to warm it up again, or whether on the contrary you turn away from it indifferently, it is you who give it its meaning and make it what it is. For in itself it’s nothing but matter for human action, and Christ came to teach you that you are responsible for yourself and your suffering. It is like stones and roots but you, you are beyond your own suffering, because you shape it according to your will. You are light, Bariona. Ah, if you knew how light man is. And if you accept your share of suffering as your daily bread, then you are beyond.

Then you will discover that truth which Christ came to teach you and which you already know: you are not your suffering. Whatever you do and however you look at it, you surpass it infinitely; because it means exactly what you want it to. Whether you dwell on it as a mother lies down on the frozen body of her child to warm it up again, or whether on the contrary you turn away from it indifferently, it is you who give it its meaning and make it what it is. For in itself it’s nothing but matter for human action, and Christ came to teach you that you are responsible for yourself and your suffering. It is like stones and roots but you, you are beyond your own suffering, because you shape it according to your will. You are light, Bariona. Ah, if you knew how light man is. And if you accept your share of suffering as your daily bread, then you are beyond.

The world and your own self, Bariona, because you are for yourself a perpetually gratuitous gift.

You are suffering and I have no pity at all for your suffering, for why wouldn’t you suffer? But there is this beautiful inky night around you, and there are these songs in the stable, and there is this beautiful hard dry cold as merciless as a virtue, and all of this belongs to you. It is waiting for you, this beautiful night. It is waiting for you by the side of your road, timidly and tenderly; because Christ has come to give it to you. Fling yourself toward the sky and then you shall be free, O expendable creature among all the expendable creatures, free and breathless and astonished to exist at the very heart of God, in the kingdom of God who is in heaven and also on earth.

BARIONA: Is that what Christ came to teach us?

BALTHAZAR: He also has a message for you.

BARIONA: For me?

BALTHAZAR: For you. He has come to tell you, let your child be born. He will suffer, it’s true but that isn’t any of your business. Don’t pity his suffering, you have no right to, because he is free, free to rejoice eternally in his existence. You were telling me before that God has no power over human freedom, and it’s true. But so what? A new freedom is going to shoot up toward heaven like a great pillar of bronze. Christ is born for all the world’s children Bariona. He is come to tell “You should not keep from having children. For even the blind and the disabled and the unemployed, and all the prisoners there is joy.”

Bariona’s rage turns to hope, a fatherly hope that wants what is best for each of his children. And for a fleeting moment he understands God’s fatherly love. He is converted. His freedom is no longer a burden, but a gift, one that he will use to protect God’s son, and his own. The play ends with Bariona leading his men against Herod to ensure that he does not find the new-born Messiah.

While the nativity story sometimes feels commonplace at best, commercialized at worst, Sartre’s irreverent but fiercely honest eye reminds us of the true scandal of the incarnation —that God would deign to become man, share his life with us, and give his life so that we might live in him. Sartre’s skepticism, disbelief, and his own hubris, forced him to confront — and paradoxically freed him to see — what we often fail to encounter each Advent and Christmas. In that long Advent of 1940, and the long season of war and darkness that swept over Europe from 1939 to 1944, Sartre understood what so many Christians fail to: The incarnation is a deep, unsettling, and beautiful mystery, a gratuitous act of a loving God, who freely gives Himself to us, and calls us to do the same.

"She has carried him nine months, and she will give him her breast, and her milk will become the blood of God."

Afternote: Having presented many times on this particular work of Sartre I often get asked two questions: 1) Which character did Sartre play? 2) Did the play make an impact on Sartre? Sartre played the role of Balthazar, whose character served as an interlocutor with Sartre’s own philosophical position. In the play the nihilist, existentialist, is represented by the protagonist, Bariona, but the counterweight is Balthazar who engages in the longest soliloquies of the play. Sartre wrote to his long-time lover and philosophical equal, Simone de Beauvoir “I have written a very moving Christmas mystery, it seems, to the point that one of the actors burst into tears.” In 1962 he released five-hundred copies of the play but provided a paragraph disclaimer explaining that he wrote it out of good-will for those he was detained with, but does not address how he was so unified with Christians in his treatment of Jesus’ divinity in the play. There is no good extant version of the play in English as a monograph. A version was published in Adam International Review in 1970, and it is currently available in The Writings on Jean Paul Sartre Volume 2 (1974) pp. 72-136.