Non-Homogenized

Musings on Milk and Other Matters

Mrs. Gina Loehr

I’m beginning to think of myself as a milk connoisseur. Some people relish the subtle nuances of coffee drinking, or wine tasting, or beer brewing, but I prefer to spend my beverage-based energy on healthy, delicious, satisfying cow’s milk.

There are three distinct ways to consume dairy milk. Raw is the first, but it can be hard — though not impossible — to come by raw milk unless you own a cow. Then, there is pasteurized, homogenized milk (what we around here call “store milk”). And finally, there is pasteurized, non-homogenized milk, which can be found occasionally in stores, sold as “cream top.”

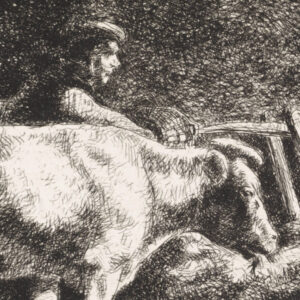

As a newlywed, I joined my husband Joe — a dairy farmer by blood and by choice — in drinking the raw milk he brought home every day. He and his ten siblings drank farm milk from birth (though their mother did boil it to make infant formula) and they are all remarkably healthy, vibrant people.

One can easily make an argument in favor of consuming raw milk for the benefits that come from ingesting the living organisms that call it home. My sister-in-law swears that switching to raw cured her bellyaches. I personally loved the fresh, full flavor and didn’t think twice about any risks since I knew the excellent production practices behind it.

One can easily make an argument in favor of consuming raw milk for the benefits that come from ingesting the living organisms that call it home. My sister-in-law swears that switching to raw cured her bellyaches. I personally loved the fresh, full flavor and didn’t think twice about any risks since I knew the excellent production practices behind it.

Alas, when I read What to Expect When You’re Expecting, I became instantly terrified not only of raw milk, but also of cats, salami, and hot dogs. So I switched to store milk, stopped petting the stray kitten that lived on our back deck, abandoned the deli, and avoided baseball games. It was a challenging pregnancy.

A few years later, before the birth of my third child, I was diagnosed as lactose intolerant. The awful news hit Joe not quite like a personal insult, but close. When I brought home my first box of soy milk, Joe asked that I please not refer to the brown liquid in the refrigerator as milk. “Bean slurry” was an acceptable alternative moniker.

I tried to adjust to the bitter, sugar added, vanilla-enhanced flavor for a few weeks, but then I learned about the phytoestrogen load in soy and its possible effects on male babies in utero, so I stopped. With the help of some Lactaid tablets my mom gave me, I was able to return to cow’s milk with no problems.

Thankfully, at some point during my next pregnancy, the intolerance issues disappeared. Unfortunately, with the birth of our sixth child, we had a new situation. After he was weaned, our baby boy began displaying symptoms strongly suggestive of a milk intolerance.

For Joe, having a son with dairy difficulties was even more uncomfortable than having a wife with those issues. It seemed like a genetic condemnation of his life’s work. Nevertheless, the problem was real and needed solving. We knew soy wasn’t for us, and those protein-deprived almond, rice and coconut fluids could not earn Joe’s respect in spite of their calcium enriched status, so we decided to try goat’s milk. It worked.

For Joe, having a son with dairy difficulties was even more uncomfortable than having a wife with those issues. It seemed like a genetic condemnation of his life’s work.

Our little fellow stopped screaming and it looked as though we had managed to find an authentic dairy alternative to cow’s milk. Friends with a neighboring goat farm would bring over a quart a week of home pasteurized milk and we (freely) paid them the exorbitant price that we would have been paying to pick some up at the grocery store.

But then I got to thinking.

“I wonder if it’s not so much cow’s milk as it is homogenized cow’s milk that causes these issues.”

I knew enough about the process to understand that homogenization blasts cream molecules into tiny bits that can be integrated uniformly into the rest of the milk. I wondered if, perhaps, the digestion process of handling these tiny fat bits was somehow different from the process of digesting whole, natural cream. Maybe this baby’s body had a problem with that process. So, at risk of another sleepless night for baby and mama, I decided to learn how to pasteurize our own cow’s milk.

It wasn’t as hard as I thought it would be. Heat the milk up just so, cool it down and enjoy. No special equipment necessary (though I did make the mistake, initially, of buying a home pasteurizer machine that took up half of a kitchen counter and sounded like a hurricane). We gave the drink to our little man — fresh, unhomogenized cow’s milk — and much to my surprise and my husband’s relief, he was fine. We tried it again the next day. It worked. And again. It worked. The child was perfectly tolerant. I wondered if he had possibly just grown out of his issues, so eventually I snuck in some store milk. No good. In a matter of hours the symptoms returned. So I continued pasteurizing milk and thought of all the poor souls in the world who might be able to cure a host of discomforts if they had access to non-homogenized cow’s milk.

It wasn’t as hard as I thought it would be. Heat the milk up just so, cool it down and enjoy. No special equipment necessary (though I did make the mistake, initially, of buying a home pasteurizer machine that took up half of a kitchen counter and sounded like a hurricane). We gave the drink to our little man — fresh, unhomogenized cow’s milk — and much to my surprise and my husband’s relief, he was fine. We tried it again the next day. It worked. And again. It worked. The child was perfectly tolerant. I wondered if he had possibly just grown out of his issues, so eventually I snuck in some store milk. No good. In a matter of hours the symptoms returned. So I continued pasteurizing milk and thought of all the poor souls in the world who might be able to cure a host of discomforts if they had access to non-homogenized cow’s milk.

Initially, we were very cautious about letting our son consume any dairy products other than our milk, but by about two-and-a-half years of age, whatever digestive issues he had had were gone, and he was able to tolerate any dairy without ill effect. So I stopped bothering about pasteurizing, and everyone but Joe went back to drinking store milk.

We go through a lot of milk. Six kids plus mom equals about a gallon of store milk consumed a day. At two dollars and fifty cents a gallon, that adds up to roughly seventy dollars a month. This month — and it varies — the farm made about one dollar and twenty-five cents a gallon. So it would cut our cost in half to pasteurize it ourselves. But that requires extra time and effort. Or so I thought until COVID-19 quarantine hit. When milk started flying off the shelves at the grocery stores, we needed another solution. We began giving our older kids raw farm milk, which they prefer. But I am still traumatized by that reading from pregnancy which bothers me when I drink raw milk or serve it to the younger kids. So I fired up my instant pot and began pasteurizing again.

Then I realized something.

Ironically, I had been driving to town several times a week to buy milk — the very substance that my husband spends so many hours every day laboring to provide for the world, the liquid that is almost constantly refilling a huge refrigerated tank just down the road a stretch. More often than not, I would make trips to the grocery store because we were getting low on milk, of all things.

More often than not, I would make trips to the grocery store because we were getting low on milk, of all things.

Because of quarantine, I suddenly realized that I didn’t have to disrupt our domestic rhythm by hopping in the car so frequently. In fact, by using the milk we had on hand — along with other foods provided by our life on the farm — I was able to stretch comfortably the time between trips to town to three weeks. This was a revelation. I thought that pasteurizing milk was an extra chore, and had abandoned doing it in the pursuit of efficiency. (It takes about an hour.) But I now realize that pasteurizing actually saved me time — lots of time — because it eliminated an unnecessary extra trip into town. I don’t know what I hadn’t thought of this before. I suppose sometimes we just do things a certain way, without thinking, because we have always done things that way or because everybody else does things that way. I suppose sometimes we can all be a little too homogenized.

How to Pasteurize Milk

If you can get a hold of some raw milk, you too can pasteurize it on the stovetop or in a pressure cooker.

Heat milk on the stove over medium heat, or in a pressure cooker on yogurt setting, to one hundred and sixty-one degrees Fahrenheit and hold it there for sixty seconds. This kills the organisms present in the milk. Then, put the pan of milk into a water bath in the kitchen sink. Surround it with cold water and ice until it cools to around seventy degrees Fahrenheit. Then, refrigerate until it reaches a comfy drinking temperature, shake, and enjoy!Or, you can skip the shaking, and skim the cream off the top instead. Use it to churn up some fresh butter, homemade ice cream or your own delicious whipped cream.