Chesterton's

Swordstick

Mr. Michael Warren Davis

Every C. S. Lewis book published by HarperCollins carries an endorsement by John Updike, the late novelist. It says, “I read Lewis for comfort and pleasure many years ago, and a glance into the books revives my old admiration.” It makes me laugh, because Lewis would have hated that quote. Of course, if he’d met Mr. Updike, he would have been perfectly civil. He would have said, “Thank you for the nice blurb,” (if you can imagine C. S. Lewis using the word blurb) and offered to sign his copy. But, inside, he would have seethed a little.

As Lewis himself said, “I didn’t go to religion to make me happy. I always knew a bottle of Port would do that. If you want a religion to make you feel really comfortable, I certainly don’t recommend Christianity.” If his books made us comfortable, he would consider it a bad job.

Having been converted by Lewis from a very comfortable, “liberal” version of Christianity to a more arduous orthodoxy, though, I can say that Updike is right. Of course he is. There are very few pleasures so wholesome—or so pleasing—as sitting in a familiar chair with a cup of tea and a copy of Mere Christianity or The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe.

Having been converted by Lewis from a very comfortable, “liberal” version of Christianity to a more arduous orthodoxy, though, I can say that Updike is right. Of course he is. There are very few pleasures so wholesome—or so pleasing—as sitting in a familiar chair with a cup of tea and a copy of Mere Christianity or The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe.

Both works are challenging. But Lewis wasn’t like so many modern writers, who “challenge us” just because they like to watch us squirm. He kindly, patiently urges us towards something—something better than what we had before. Lewis has the “Christ-like union of tenderness and severity” he found in George MacDonald. That union is impossible to fake. It’s found only in those men who speak and write for the sake, not of power or fame, but of love.

Hence, too, his signature wit and warmth. Opening one of Lewis’s books, you don’t hear him thundering from the rostrum. We always seem to find him in his own rooms. That’s because he’s our friend. We’re like the disciples of John the Baptist who ask, “Where are you staying?” Lewis says, “Come and see.” (Jesus wasn’t only recruiting followers: He was making friends.) Reading C. S. Lewis, you can practically feel the fire burning in the hearth of his study at Oxford. You can smell the old ale-soaked wood at the Eagle and Child. It makes you want to put on a tweed jacket, light your pipe, and go for a long walk to a little country church.

You can smell the old ale-soaked wood at the Eagle and Child. It makes you want to put on a tweed jacket, light your pipe, and go for a long walk to a little country church.

It is incredible to think that this man, Clive Staples Lewis—“Jack” to his friends, like you and me—was a combat veteran. Lewis served valiantly in the First World War, enlisting at the age of eighteen. At nineteen, he was promoted to Second Lieutenant. At twenty, during a major battle near the French town of Riez-du-Vinage, an artillery shell exploded near his position. Lewis was badly injured; shrapnel riddled his body and punctured his lung. “Just after I was hit, I found (or thought I found) that I was not breathing and concluded that this was death,” he later recalled. “I felt no fear and certainly no courage. It did not seem to be an occasion for either.”

So, too, with another “cozy” writer: J. R. R. Tolkien. The author of The Hobbit was twenty-four when he fought in the Battle of the Somme, the bloodiest of World War I. He wasn’t injured, but he did come down with a horrible disease then known as trench fever. He was deemed unfit for further service and medically discharged from the army. That’s when he began to write.

What’s curious is that Tolkien went out of his way not to draw inspiration from his experiences in the War. (Whether he succeeded is another matter.) As he wrote in the introduction to the second edition of The Lord of the Rings, “The real war does not resemble the legendary war in its processes or its conclusions.” Tolkien confessed, “I cordially dislike allegory in all its manifestations, and always have done so since I grew old and wary enough to detect its presence. I much prefer history, true or feigned.”

What’s curious is that Tolkien went out of his way not to draw inspiration from his experiences in the War. (Whether he succeeded is another matter.) As he wrote in the introduction to the second edition of The Lord of the Rings, “The real war does not resemble the legendary war in its processes or its conclusions.” Tolkien confessed, “I cordially dislike allegory in all its manifestations, and always have done so since I grew old and wary enough to detect its presence. I much prefer history, true or feigned.”

His own history he summed up rather grimly: “The country in which I lived in childhood was being shabbily destroyed before I was ten, in days when motor-cars were rare objects (I had never seen one) and men were still building suburban railways.” Also, “By 1918 all but one of my close friends were dead.”

This is the man who also said, “If more of us valued food and cheer and song above hoarded gold, it would be a merrier world.” He spoke from experience.

All of this came as a surprise to me, though maybe it shouldn’t.

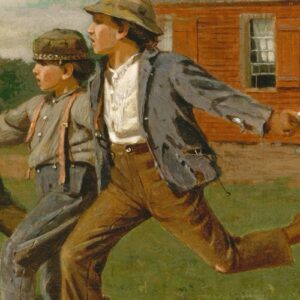

The modern manly-man would probably scoff at Narnia and Middle-Earth. That’s kiddie stuff. But if you’ve watched your best friends die, shot by German snipers and blown apart by German shells, you might come away with a different attitude.

Maybe you wouldn’t go in for the same things as the modern manly-man, like Call of Duty and the Punisher. You’ve had enough violence and death for a lifetime; all that make-believe doesn’t seem like much of a hobby. There’s no need to fantasize about the darkness when you’ve walked through it. Once you’ve met evil face-to-face, you might prefer to look for other playmates. You want to surround yourself with good things.

That’s exactly what they did.

Which might be why—despite many, many attempts—we’ve never seen the likes of Lewis or Tolkien again. It’s not just that they were true Christians (though I think that helped). It’s the high moral seriousness they brought to their books. We call their novels “fantasy” but they were, perhaps, the last of the realists. You can’t have flights of fancy like that unless you know something about life. Lewis and Tolkien knew victory and defeat, fear and courage, shame and valor. They knew it first-hand, in a way few of us today can imagine.

We call their novels “fantasy” but they were, perhaps, the last of the realists. You can’t have flights of fancy like that unless you know something about life.

“The glory of God is man fully alive,” as St. Irenaus once said. Lewis and Tolkien were real-life men.

They certainly weren’t escapist, like so many of today’s fantasy writers. Just the opposite. In both The Chronicles of Narnia and The Lord of the Rings, the authors seem to be explaining (to themselves, if no one else) what all the fighting was for, why it was all worthwhile. Because their novels are a celebration of things that are worth more than life, of things worth dying for—things like home, family, nature, love, justice, honor, and sacrifice, to name just a few.

Each of the authors was fully prepared to die for them, too, in real life. That can’t help but make its mark.

The coziest author of all, however, was surely G. K. Chesterton. Chesterton first made his mark as a literary critic, and is widely credited with reviving interest in the work of Charles Dickens. He earned lasting fame as the creator of Father Brown, the only serious rival of Sherlock Holmes for title of World’s Greatest Fictional Detective.

The coziest author of all, however, was surely G. K. Chesterton. Chesterton first made his mark as a literary critic, and is widely credited with reviving interest in the work of Charles Dickens. He earned lasting fame as the creator of Father Brown, the only serious rival of Sherlock Holmes for title of World’s Greatest Fictional Detective.

Yet his devotees know him best as the greatest Christian apologist of the 20th century. His little book Orthodoxy has sold millions of copies and helped bring thousands of new Christians into the Church—including C. S. Lewis. While many social critics are funny, most would fall into the category of “acerbic wit.” Not Chesterton. He wasn’t only the funniest man of his age, but also the kindest. H. G. Wells (a contemporary and an ardent atheist) said the thing he hated most about Chesterton was that he couldn’t bring himself to hate Chesterton.

Chesterton was forty when the first Great War broke out—too old to fight—though he expected to perish in the second: Chesterton famously declared that he and his friend Hilaire Belloc would “die defending the last Jew in Europe.” Still, if not quite a soldier, biographers attest to the fact that he carried a revolver and a swordstick with him everywhere he went.

That’s a little surprising, too. As an arch-Medievalist, of course, Chesterton couldn’t be squeamish about violence. Yet I would have expected something a little more symbolic — and maybe a bit more theatrical. I would have been less shocked to read that he went around with a claymore on his back than a little gun in his pocket.

Because the point of a revolver, like a swordstick, is that you keep it hidden. Unlike a saber, such things have no ceremonial purpose. They kill people; that’s all they’re good for. Like a knight of old, our man Gilbert was ready to spring into action at a moment’s notice (to whatever extent a 400-pound man can spring) to defend the honor of a lady, the poor, or Holy Church.

It reminds me of a quote by Theodore Roosevelt: “Over-sentimentality, over-softness, in fact washiness and mushiness are the great dangers of this age and of this people,” Teddy said. “Unless we keep the barbarian virtues, gaining the civilized ones will be of little avail.”

Lewis, Tolkien, and Chesterton had both the civilized and the barbarian virtues. All three were known for their warmth and wit. They were God-fearing. They were charitable, in every sense of the word. All of them famously loved children. They were cultivated, educated, and well-mannered. I’ve never seen a photograph of any of them where they were not wearing a coat and tie. Yet, clearly, they were willing to fight and die to defend the things that mattered most to them.

They were cultivated, educated, and well-mannered. . . . Yet, clearly, they were willing to fight and die to defend the things that mattered most to them.

They didn’t suffer from a “weak excess of sensibility”; nor were they lost to the “slumber of cold vulgarity.” They were gentlemen, but they weren’t soft men. They were latter-day knights, civilized barbarians. They were men with chests.

Yes, Lewis and Tolkien are comfortable. After spending all that time in the trenches, I think they earned that warm hearth in the study. I think they have a right to be cozy.

And would Chesterton have used his swordstick, if it came to that? There’s no doubt in my mind.

Let this be a lesson to us all. Many of us no doubt get to feeling “cozy” when we read Lewis, Tolkien, and Chesterton. As well we should! But they weren’t only poets and scholars. They were warriors. They were tender and severe, like Our Blessed Lord. They invite us to embrace their principles: the principles of Christianity. Yet once we embrace them, we have to fight for them. Men always fight for the things they love.

Jesus was also an eloquent preacher. Thousands would gather to hear him speak. And what words he spoke. After all of his sermons, though, there would be men and women in the crowd who found his sayings too hard. Some would walk away. Others wanted to stone him. He never apologized, adulterated, or dumbed-down. He spoke the truth with kindness and love, but if men shut their hearts to that truth, he didn’t budge.

Jesus was also an eloquent preacher. Thousands would gather to hear him speak. And what words he spoke. After all of his sermons, though, there would be men and women in the crowd who found his sayings too hard. Some would walk away. Others wanted to stone him. He never apologized, adulterated, or dumbed-down. He spoke the truth with kindness and love, but if men shut their hearts to that truth, he didn’t budge.

Lewis and Tolkien and Chesterton do everything in their power to make the truth attractive to us. But on the fundamentals they are absolutely inflexible. Many of us who fall in love with their writings would rather do without the hard sayings, but they won’t let us.

Chesterton won’t be the jolly fat man with the gap in his teeth. We can’t get far in his writings without finding some praise of the Crusades. Lewis won’t be the quaint Oxford don who told the lovely fairy-stories: every time we read the Chronicles, Susan doesn’t make it back to Narnia in time for the Last Battle, because she’s become a strutting, self-important snob.

And while many of us feel a certain kinship for Bilbo and Frodo and Samwise, we men aren’t supposed to identify with the hobbits. We’re supposed to identify with the men: the brave Aragorn, the unfortunate Boromir, the wicked Wormtongue.

Hobbits have all the civilized virtues, and none of the barbarian. But that isn’t our lot. We need both in equal measure. We need to be soldiers as well as scholars. We should be at home both at the hearth and in the field, even the field of battle.