Don't Be a Stranger

On Names & Naming

Mrs. Libby O'Neill

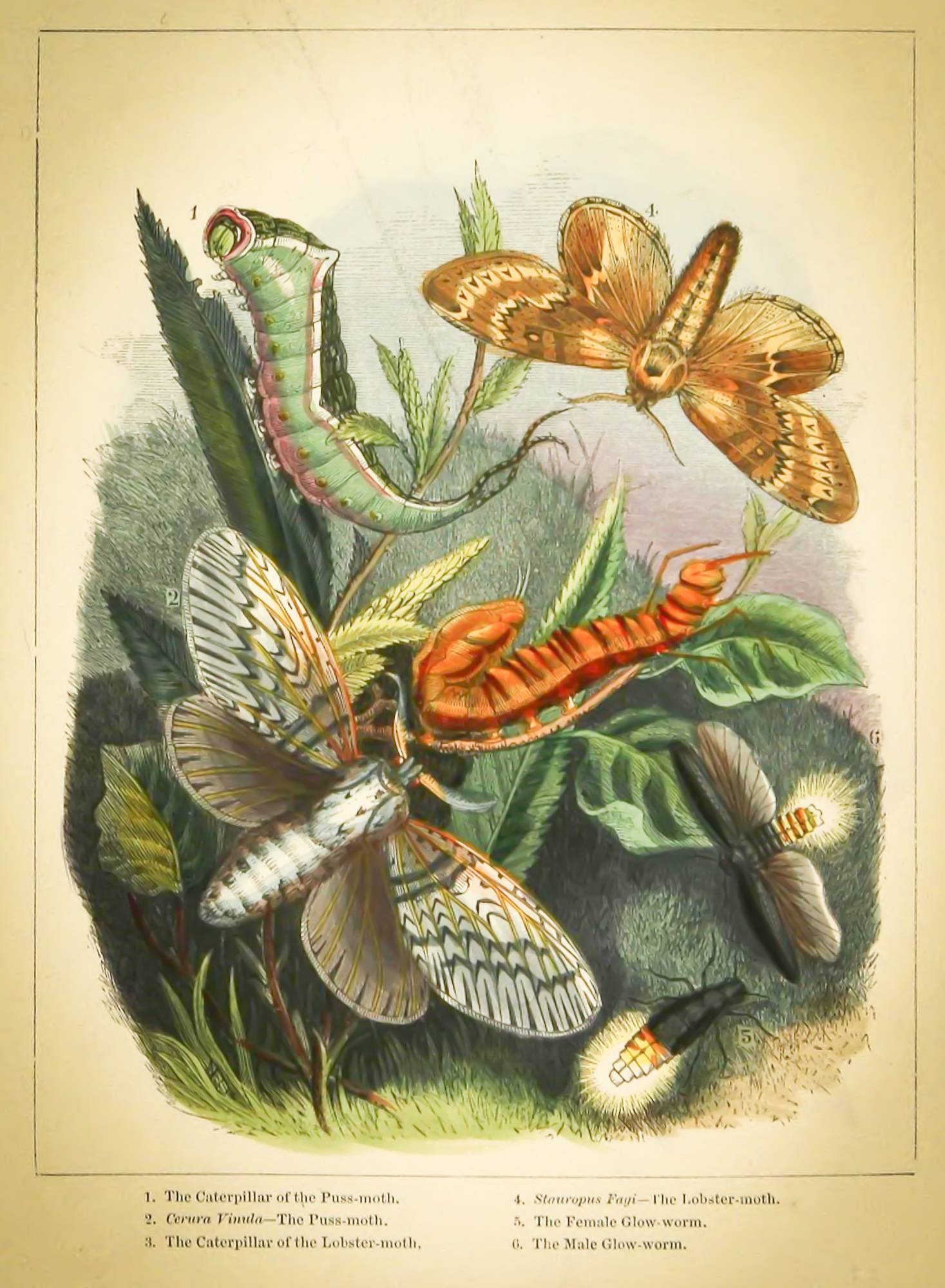

No one makes you face your ignorance about the world like a child, whose limited time on earth throws into sharp relief the use you have made of your own time. Years ago, my then three-year-old son and I watched a caterpillar make its way across the brick siding of our house. After several minutes, my son, with full confidence in a response, asked me what kind of moth it would become. I had no idea, and I told him so. The look on his face, which revealed an inability to understand how a human could spend twenty-five years on this earth and not bother to know the names of her fellow inhabitants, is one I will never forget.

It wasn’t the first time I failed him in such a matter, and it wouldn’t be the last. My son, with now a full decade of bug catching under his belt, has already passed me by in the insect-identification department. And, luckily for us both, he knows by now to take his questions of a more botanical bent to my husband, who never fails to fill him in on the flora he’s found. But that look, not without its traces of disappointment and disdain, left its mark on me. I’ve since spent much time wondering what we leave on the table, when we never learn a thing’s name.

Perhaps, for some of us, this entry into a world of knowable, nameable things begins with the realization that the various bits and pieces of creation, in which we find ourselves immersed, do, in fact, have names. They’ve been seen before we’ve seen them, known before we’ve known them (if we choose to know them at all), and their very nature is made more accessible to us once we can call them what they are. While Latin names provide a wealth of information to those who can remember them, even the common names of plants and animals allow us to appreciate the genius and joy others have brought to this task of naming. The walker of the woods and the tiller of the fields know, in an intimate way, the personality of their fellow living things. God gave us the Tufted Titmouse, the Jack-in-the-Pulpit, and the mudpuppy, but we have the great naturalists and common farmers who came before us to thank for their names.

The walker of the woods and the tiller of the fields know, in an intimate way, the personality of their fellow living things.

For as long as God has been creating things, it has been our duty to give them names. “So out of the ground the Lord God formed every beast of the field and every bird of the air, and brought them to the man to see what he would call them; and whatever the man called every living creature, that was its name.”

Having created the animals in all their splendor, why does God bother to have them named? What purpose does it serve? God has done the work of creation; Adam’s job seems superfluous. On a surface level, names come in handy as linguistic shortcuts. I don’t have to describe to you the six-foot tall flower with a black center and orange petals. You know what I mean when I say “sunflower.” Using agreed-upon names saves us from the tedium of defining a thing each time we reference it. But if God insists on this naming of his creations as the first assignment of mankind, there’s more to it than this.

Having created the animals in all their splendor, why does God bother to have them named? What purpose does it serve? God has done the work of creation; Adam’s job seems superfluous. On a surface level, names come in handy as linguistic shortcuts. I don’t have to describe to you the six-foot tall flower with a black center and orange petals. You know what I mean when I say “sunflower.” Using agreed-upon names saves us from the tedium of defining a thing each time we reference it. But if God insists on this naming of his creations as the first assignment of mankind, there’s more to it than this.

As anyone who has faced the somewhat daunting task of naming a child can attest, there is a certain pressure that accompanies the job. We want to get it right. We want that name to get to the heart of the matter — to convey, on an intuitive level, the essential nature of the person in question. More than once, my husband and I have waited to choose a name for a child until we have met that baby, and looked through the tiny windows of his soul to see exactly who he is. Discovering the sex helps too. But what does it mean to get it right? What does it matter? The things we see in nature are no more called into existence by our naming them than our children are. One of our daughters went unnamed for a full twenty-four hours: her existence and needs were no less real for that.

The pressure we feel in this naming process comes from an understanding of what a good name should do. A good name draws us, immediately and intimately, into the true nature of what we see. More than a linguistic shorthand, it provides direct access to the spirit and substance of one of God’s creations. Our name for something doesn’t make it what it is, or worse, what it isn’t. But calling a thing by its name invites us into deeper communion with the reality that surrounds us — the reality that (luckily for us) exists regardless of what we say it is.

Our name for something doesn’t make it what it is, or worse, what it isn’t. But calling a thing by its name invites us into deeper communion with the reality that surrounds us. . . .

Learning someone’s name opens the door to an encounter and, if we’re lucky, a relationship that brings us joy. Ultimately, being surrounded by plants, animals, and phenomena for which we don’t have names is akin to living in a house with people whose names we never bother to learn. To know and use the names of the weeds in our backyard, the songbirds in our skies, and the trees on our street, is to care, in an interested and interactive way, about the world we inhabit. Nomenclature is fundamental to knowing and opens the door to intimacy.

Learning nature’s names has been a process for me, a road I will be traveling all my life. I learn alongside our children, who I’m proud to say recognize most of what they see in our backyard (Peterson field guides and the Cornell Lab of Ornithology tools are most helpful). And while I’m still working on discerning one oak from another, I no longer belong to the group of people my husband calls “the ones who call all evergreens a pine.” It doesn’t take a degree in botany or entomology, but greeting the chickadee when he sounds his signal, and cursing the Creeping Charlie encroaching on the garden, create a feeling that when we’re in nature, we’re among friends (or enemies, as the case may be). This knowing where we stand, and with whom, is a grounding and comforting mode of existence, one I suspect many of us are craving. It’s also a great way to impress a three-year-old.