To Create & To Remember

A Reflection on Moving, Mementos,

and the Meaning of Home

Mrs. Gina Loehr

Black and white floor tiles make me happy. The comforting joy that those contrasting squares conjure in my soul has its roots in my grandmother’s basement. Her subterranean floor also had a shuffleboard court painted on it, and wallpaper-embellished circular posts drilled into it, a wet bar set on top of it, and a steel office chair with slippery greased wheels, which spun around on it when the clandestine vehicle was pushed by an obliging cousin.

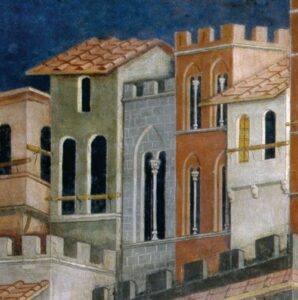

Everyone loved that house on Rondeau Ridge, and not just because of the checkered basement, or the mural of Italy in the dining room, or the honeysuckle growing up on the ledge in the backyard. Mostly, we loved it because of the memories we made there. The delectable dinners we enjoyed at the big table, the games we played in the twin bedroom, the joys and sorrows we shared in the living room, which hosted both baptism and funeral gatherings. My grandmother raised her children in that house. And she cared for her dying husband, who was ill from chemical exposure during the war, and later her eldest daughter, who was struck by cancer while herself a young mother, right up to the days of their death in that house.

Eventually, it was sold, and we sadly bid the place farewell. But this happened so that Grandma could move into her mother’s house, which was itself a sort of homecoming. And she brought countless things with her from Rondeau Ridge. We’re a nostalgic family, and we often imbue material objects with a significance beyond what their objective status deserves. Now that she has passed, I treasure in my home a few of those special objects that mean Grandma’s House to me: the gold and ivory 1950s telephone, the circle chair, the bronze hamper with the mesh sides and blue cushion on top.

My grandmother came over from Italy when she was young. She didn’t have the luxury to bring much along on the ship as mementos of home — or at least not anything terribly large. But there is the statue of St. Michael. Room was made for that. And there were other bits and pieces, those as could be carried by hand and fit in the luggage of a one-way transatlantic passage. Attending them all, were the stories and memories of childhood in her beloved village of Valle dell’ Angelo, her original home, named for that same saint. These survived the voyage and the one-hundred-and-three years she spent on Earth. So home traveled with her in this sense, across the ocean and across town and across the span of her life.

My grandmother came over from Italy when she was young. She didn’t have the luxury to bring much along on the ship as mementos of home — or at least not anything terribly large. But there is the statue of St. Michael. Room was made for that. And there were other bits and pieces, those as could be carried by hand and fit in the luggage of a one-way transatlantic passage. Attending them all, were the stories and memories of childhood in her beloved village of Valle dell’ Angelo, her original home, named for that same saint. These survived the voyage and the one-hundred-and-three years she spent on Earth. So home traveled with her in this sense, across the ocean and across town and across the span of her life.

These survived the voyage and the one-hundred-and-three years she spent on Earth. So home traveled with her in this sense, across the ocean and across town and across the span of her life.

But this all makes me wonder: what is home?

Does home lie at the point where experiences and emotions intersect with floor tiles and furniture? Or does the reality of home transcend anything physical?

My parents have just moved into a house better suited to their state in life, and if it weren’t for the fact that they brought with them the dining room set from Grandma’s house — and various items from my childhood home — the place might still be beautiful, but it would also seem entirely foreign.  Instead, it feels as though new life has been breathed into the family legacy. There is a continuity of home, in spite of the new floorplan and bigger windows and different view, in large part because of these traveling mementos.

Instead, it feels as though new life has been breathed into the family legacy. There is a continuity of home, in spite of the new floorplan and bigger windows and different view, in large part because of these traveling mementos.

Yet, in contrast to this experience of the “home” that need not be established in a particular house, I see the witness of my husband and his family. I left my (ninth) home in Ohio to move to Joe’s (only) home in Wisconsin. There was never any question of his leaving the farm, which has been in the family for nearly one hundred and fifty years. His father grew up in the same house that his father and his father’s father and his father’s father’s mother called home. Joe lived there until migrating into the adjacent house, a little before we got married. His mother, along with a sister, and a brother and sister-in-law and their children, live in the big house now, and the notion of ever selling it seems absurd. My nostalgic attachment to a few items that have traveled alongside me to the (now ten) places I have lived sometimes seems absurd to Joe, but perhaps that’s because he doesn’t need to attach comforting feelings to any portable objects since he has never had to leave his home.

Well, alright, he did move next door. But our house, also situated on the now-expanded family farm, has gained a permanent status and is really just a satellite location of the original farmhouse. We have always planned to stay on the farm and, God willing, expect that we will never move. So now I suppose I have the best of both worldviews: Grandma’s phone on my desk, and life in a house that will never be sold.

I’ve noticed that this unquestioned rootedness gives Joe and me a wonderful freedom to establish our home as we like it, without the “threat” of the housing market lurking around any corner. Re-sale value is not part of our domestic calculations. When Joe finished the (ancient stonewall) basement to make a playroom for the kids a few years back, guess what sort of floor tiles we chose?

I’ve noticed that this unquestioned rootedness gives Joe and me a wonderful freedom to establish our home as we like it, without the “threat” of the housing market lurking around any corner.

I have, quite honestly, no idea whether black-and-white squares in a stark checkerboard arrangement are currently fashionable or not. I imagine they’ve gone in and out of favor over the decades. But it doesn’t matter to me whether the floor in our basement looks trendy or ridiculous; it’s fun, and it’s meaningful. No one else has to declare it stylish, and we need not judge its value with any economic measuring rod. That floor enriches our life because every time I walk downstairs, a little wave of memories — mostly happy, sometimes sad — washes over me. And daily, we’re creating memories down there for our children.

And that, I suppose, is what ties this all together — Joe’s experience of home as something planted and my experience of home as something portable. In both cases it is a matter of memory, of continuity with the past. Maybe it is even a matter of continuity of self. Thomas Aquinas (invoking St. Augustine) held that the image of our triune God “is found in the soul according to memory, understanding, and will.” We think often of free will and understanding as being definitional in what makes us human, but memory is inseparable from them. And, in a sense, our particular memories must be a part of what make us not just human, but particular humans.

A home is a physical conduit of memories. It is more than a shelter and pile of possessions, and more than an idea that we carry around with us. It is the place where most of our memories are made and the place where they are most viscerally remembered.  Its structure, its decor, its myriad little trappings, the clothesline and the climbing tree out back, the retained scent of summer breezes and winter fires and thousands of meals we’ve cooked and eaten alongside the people whom we most deeply love in all the world — these things all conspire to keep memory alive, not just in the sense of something retained but in the sense of something living.

Its structure, its decor, its myriad little trappings, the clothesline and the climbing tree out back, the retained scent of summer breezes and winter fires and thousands of meals we’ve cooked and eaten alongside the people whom we most deeply love in all the world — these things all conspire to keep memory alive, not just in the sense of something retained but in the sense of something living.

It seems to me that such dependable continuity, such sense of self within an arc of time (whether in a place or places) is precisely the effect that home ought to produce. I fear that these anchoring realities are less and less familiar to many folks these days, whether that results from our displaced lifestyles, from chasing happiness specifically “away from home,” from the constraints of home-as-investment, or from the materialistic obsession with home-as-showplace.

These choices and perspectives have their cost to us, both societally and personally. They are hard to reconcile with the goal of home as the contiguous seat of human life and familial love, held fast across the decades. Even harder to reconcile is the fact that we do not always choose the memories we make. All people will sometimes have, and some people will always have, acutely painful memories of a home and the trauma with which sin has tainted it. But the point is not to pull us backward into to the past. The point is that the space we live in can help us integrate the past, both its good and its bad, neither fleeing from it nor being slaves to it. Thus we ourselves become integrated. We experience ourselves as continuous beings, who live in the present, relate to the past, and direct ourselves toward an eternal future.

And that, of course, is the ultimate aim of all of this. That is the purpose of home and of all our time there, be it in my grandmother’s basement or in one of the apartments I occupied for a year or in the farmhouse my husband’s family has occupied for a hundred and fifty. Some earthly places may be more anchoring than others, but in the end all are equally fleeting. A home is worthwhile, both to create and to remember, because these conjoined activities have the power to produce a kind of celestial preview, a foretaste of our true home, our final resting place, God-willing, where joys will not end.