The Present

Dr. Jeff Gardner

I turned fifty-seven this year. Not that there is anything remarkable about that. I am at that point in life where I no longer see the passage of time as a wondrous thing, but I don’t fear it either. I could be afraid of it; I have reason to. All of the men in my family one generation above me died by the age of sixty. My father and his two brothers lived hard-drinking, hard-driving lives, dying at ages sixty, fifty-eight, and fifty-nine. While I don’t smoke and only drink occasionally, being closer to sixty than fifty is sobering.

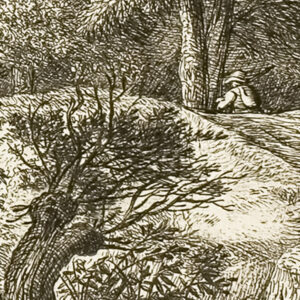

When I was in my thirties, during a particularly difficult time in my life, a good friend took me for a hike on the shore of Lake Superior. As we walked along he suggested that although things were hard now, life could be viewed as a series of stages, each lasting about twenty years. He said that each stage had its own distinct character but was not lesser or greater than any other, and each was an opportunity for a new beginning.

I appreciated my friend’s kindness but I was not wholly convinced by his “equal but different” stages of life theory. Perhaps cynically, I suspect that our time here is more like The Duration of Life folktale recorded by Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm. It goes something like this:

God created the world and gave each animal a duration of life. He gave the donkey thirty years, but when the donkey asked to be spared so much toil, God in His mercy took away eighteen years.  God gave thirty years of life to the dog. But the dog begged to be spared so many years growling at everything until he was old and toothless – all bark and no bite. So God in his love took twelve years away from the dog. When God gave thirty years to the monkey, the monkey sighed, since thirty years was so long to be mocked and forced to do tricks. In His compassion God took away ten years from the monkey.

God gave thirty years of life to the dog. But the dog begged to be spared so many years growling at everything until he was old and toothless – all bark and no bite. So God in his love took twelve years away from the dog. When God gave thirty years to the monkey, the monkey sighed, since thirty years was so long to be mocked and forced to do tricks. In His compassion God took away ten years from the monkey.

Then God gave the man thirty years of life, but the man complained saying, “Oh Lord, I am man, and at thirty years I will have just begun to live, and then I am to die? Lord, this life is not fair, I need more!”

In his consolation, God gave the donkey’s eighteen years to the man. But the man complained louder, and God gave the dog’s twelve years to the man, but the man was not content, complaining even more. So in his benevolence, God gave the man the monkey’s ten years. But the man was not satisfied, and he cursed God. In his wrath God sent the man away, leaving him alone with his selfishness and lack of gratitude.

And so it goes that for the first thirty years of life man lives as God’s creation, happy and content. For the next eighteen years, man toils like a donkey, working for others and carrying them on his back. For the next twelve years, he yaps like a dog, whining and barking at everything just beyond his front door. And finally, in the last years of his life, he is mocked and ridiculed like a monkey, an object of amusement for all who are younger than him.

In crossing the threshold of my late fifties, I don’t believe that I am a monkey yet, but there are days when I worry that I am devolving into a barking dog with a strange, prehensile tail.

I don’t believe that I am a monkey yet, but there are days when I worry that I am devolving into a barking dog with a strange, prehensile tail.

But wondrous or not, a birthday needs a present. For mine, I gave myself a one-day, sixteen-mile hike. I had not hiked mileage above fifteen miles in a single day in over ten years, so obviously I was overdue for overdoing it.

Was I trying to prove something? Yes, certainly. To whom? Myself, of course. More than just hiking the miles, I wanted to prove that I could out-pace age, time, and all the heartaches and pains that come with them. An absurd proposition, I know, and as I drove to the trailhead I worried that I might be coming off as the aging male whose reasons for pushing himself are all the wrong reasons.

For my birthday hike, I took along my youngest son. At only sixteen he is remarkably strong, and, best of all, he never complains. He and I have backpacked many long treks together, some of nearly one hundred miles, pushing our way through altitude sickness, lightning storms, and freezing rain without a discouraging word from him. That’s rare in a hiking partner.

He also has a unique ability to enter into a type of trance when he hikes, a hypnotic state in which his mind clears itself and he slips into a sort of upright, forward-moving meditation. I can tell when he is stepping into “the zone” as he calls it, because his body movement takes on a metronomic canter. At that point in a hike, when he switches to mesmerized mode, I have learned to watch him closely; he can get so far “out there” that he might miss a bend in the trail and walk off into the woods.

He also has a unique ability to enter into a type of trance when he hikes, a hypnotic state in which his mind clears itself and he slips into a sort of upright, forward-moving meditation. I can tell when he is stepping into “the zone” as he calls it, because his body movement takes on a metronomic canter. At that point in a hike, when he switches to mesmerized mode, I have learned to watch him closely; he can get so far “out there” that he might miss a bend in the trail and walk off into the woods.

I am not as fortunate as my son, and hiking does not clear my head or calm my mind. For me, it is just the opposite. Hiking supercharges my brain, and as we set off from the trailhead, my thoughts jumped around like a puppy just let off the leash.

Unfortunately for me, my mind’s favorite preoccupation is to rerun fragments of pop tunes over and over, using them as to harp on worries I wish I could leave behind in the van. Here’s just a small sample of the inanities that I endured by mile seven of the hike: “If you get too cold, I’ll tax the heat, If you take a walk, I’ll tax your feet, ‘cause I’m the taxman”

And then repeat until I snapped at myself, “Is it April 15th, already!?”

Decoding the message and resolving to take action gives me a short reprieve, but it is not long before the music starts up again: “Too blind to know your best, hurrying through forks without regrets, different now, every step feels like a mile…”

The snippet played over and over until, stressed out, I asked myself, “How long is this section of the trail? Did I miss the turn-off? Should I look at the map again?”

And so on.

My head will use these lyrical fragments as moral allegories that, somehow, I seem to need to keep me on the straight and narrow. True, over a given trip, I do cover some useful ground, and the outcome is often beneficial. But the process is at times more exhausting than the hike. Like being dragged to an involuntary therapy session, I can only make the musical interrogation stop when I agree to do something about whatever it is that my mind is fixated on.

My head will use these lyrical fragments as moral allegories that, somehow, I seem to need to keep me on the straight and narrow.

While not clearing my head, hiking turns my senses all the way up. That’s my drug, my “hiker’s high,” and as we moved from pine forests to deep, lush stream bottoms choked with ferns and undergrowth, the colors of the forest became so bright, the sounds of the birds and our footfalls so clear that even my sense of time changed.  By mid-hike, the temperature had crept up into the nineties, and the fifteen minutes we spent by the pool of a clear, fast-running stream seemed like all afternoon. The hour that we spent climbing the steep grades just past the halfway point on the trail felt like an eternity. Even my senses of taste and smell are heightened to ridiculous levels, with a lowly handful of sunflower seeds tasting like a banquet.

By mid-hike, the temperature had crept up into the nineties, and the fifteen minutes we spent by the pool of a clear, fast-running stream seemed like all afternoon. The hour that we spent climbing the steep grades just past the halfway point on the trail felt like an eternity. Even my senses of taste and smell are heightened to ridiculous levels, with a lowly handful of sunflower seeds tasting like a banquet.

But there are upper limits to this sensory nirvana, and as the hot day wore on the trek was reduced to a sweat-driven, chafing calculation of how much water we should drink at a given spring, and how far it would be to the next one.

By mile thirteen, with only three miles to go, there was no question that I would finish the hike. I thought that I had gotten the gift that I had come for, plus a bonus gift of a blister on my right heel. But as we trekked into the hottest part of the day, the trail was not finished with me.

It was just past mile thirteen, with my son some twenty yards behind me, that I first saw the black bear out of the corner of my right eye. I had no idea how long it had been there, walking parallel to me, pacing me, mirroring me. When I looked up at it, it looked up at me. When I looked back at my trail, it looked back at the ground.

And it was a black bear, so black that at first glance I did not see it so much as I saw a gaping blank space among the trees where it should have been. No color and no texture in the place that it occupied, as if someone had used a pair of magic scissors to cut out a bear-shaped hole in the forest.

And then I stopped. And the bear stopped. And we just stared at each other. And the prodding music in my head stopped. And as I stood, stopped, I was not on the trail anymore. Yes, I was in the forest, on the trail, but I was somewhere else at that moment, sharing that gaze with that bear. I was completely present to and with myself. There was no time, no stages nor age. For one brief moment, I was completely where I was, who I was; I simply was, and nothing else. I did not understand what was happening, but, pleasantly, I did not feel any need to understand.

For one brief moment, I was completely where I was, who I was; I simply was, and nothing else.

Over the many years that I have spent in the mountains and the woods, I have not given much thought to animals beyond seeing them as things, features that were part of the landscape. True, some animals are always a comfort, like hearing the call of a great horned owl, while others, like the rasp of the whippoorwill when I am trying to sleep, grate endlessly on my nerves. But right at that moment, encountering that bear did something to me, moved my view of myself and my place in the world.

Way back in the past, Westerners wrote and read short descriptions of animals and the natural world. They called these writings Bestiaries and used them to frame their understanding of the natural world through moral allegory and a cosmological explanation of God’s creation. The idea was that God had designed a place for everything and everything, according to what it did, had its place. Bears, it was believed, reshaped things. It was thought that their young were born without proper form until their mothers licked them into shape, remaking them into a whole being. Because of those believed origins, the bear was called orsus, later written as ursus, which in Latin means a new “beginning,” or “undertaking.”

Can we be remade by an encounter with a man or beast? God’s creation is God’s plan, and it pushes and pulls on all of us in ways that we do not understand or are even aware of. Was the bear remaking me or, like the songs in my head, was I remaking myself through the pull of the bear? I can’t definitively say, and at that moment, the question did not even occur to me. I was being reshaped, remade, receiving a gift that I could not hold in my hands, unwrap or carry, because it was in me; it was me.

My son caught up to me and said in a terse, suppressed voice, “That’s a bear!” and “What do we do?” His voice broke the moment, and I was immediately aware of the heat, the forest, and the bear; now a thing, an animal, an object, and not an experience.

I’d like to say that I said something wise, father-to-son-like at that moment. But suddenly out of myself I defaulted to the cliché “Hey bear!” encouraging my son to do the same. The bear gave me one more glance with a look that hinted at a message I could not understand and then, slowly, it walked away into the woods.

A short while later we stopped and sat on a group of boulders while I attended to the blister on my heel. We talked excitedly about what we had seen and how unlikely it was, but my mind was detached from the conversation. I was struggling to find word handles and get a grip on what I was feeling. My body was on the boulder, yet I was back down the trail wanting to stay and linger in that moment, wanting to be eternally present.

But I couldn’t go back, and I didn’t find the words. The trail, the day, and the hike, all of it, moved forward. Time sweeps us along through our failures and successes, an emotional erosion that forms the paths of our interior landscapes. These paths become the tracks that we travel over and over with no trailheads or exits. The wise thing to do is to stay off the bad trails and stick to the ones that lead us to good places, and above all else, keep moving forward.

As we finished the hike, exhausted from the long, hot day, the music in my head restarted. But during the last mile or two, it was less frantic, less moralizing, and more patient. And when I tried, I could turn the volume down, or almost make it stop — but I did not want it to. Over and over I let it play:

“And if I die

Before I learn to speak

Can money pay

For all the days

I lived awake

But half asleep?”