Women, Men, Marxism, & Homemaking

Mrs. Noelle Mering (author, homemaker, and mother of six children) and Mrs. Gina Loehr (author, homemaker, and mother of six children) sat down to discuss their work — both the written and lived varieties. H&F recorded the conversation, which is transcribed below.

Gina Loehr: So Noelle, I have to tell you about the first time I saw one of your books. I had ordered Theology of Home. It arrived, and I took it out of the packaging, and I stood at the dining room table and paged through the entire thing, cover to cover, looking at every single photograph. I could tell I was going to love the ideas, but I just was drawn to every image that was in the book, and I thought as I was looking at the photos, “I cannot wait to read this.” It drew me in. It was beautiful. But I didn’t start reading — I set it down because I had to go make dinner!

Then my husband walked through the room and picked the book up. He started reading. He didn’t page through looking at the photos; he sat down and started reading the book. And I probably never could have said “Hey Joe, read this book about homemaking!” and expected much to happen. But he picked it up of his own interest, and it turned out he was completely captivated by the ideas in it. And finally I got a chance to start reading it, and we ended up having a great discussion after — we were both really inspired by it. So I’m curious, are there “typical” reactions of men and women to your work, and do they differ?

Noelle Mering: Thank you so much for sharing that story! I love that so much, and I think that there’s something very fundamentally female and male about that. Not exclusively so, but I find that as women, we tend to be very visual; we want to see an embodied reality.  Men sometimes can begin with the opposite approach. But we both appreciate both, you know? And they circle back to the other. So I love that you guys experienced it that way.

Men sometimes can begin with the opposite approach. But we both appreciate both, you know? And they circle back to the other. So I love that you guys experienced it that way.

I think it is just a matter of starting with things that are universal longings, things that are beautiful but also that are substantive. These are real human desires — to have home and to settle and to nurture and to establish and to be grounded in these ways. I think that those are masculine longings as well as feminine.

GL: So these “longings” we all seem to have, feeling drawn to the things of home, to the things that are real and tangible and uplifting — creating beauty within our environments — do you think that’s always been present? Or have we gone through some period where it has kind of been squelched or latent or something?

NM: I think it’s fundamental to our humanity that we have these sorts of longings, but for various reasons, they were really squelched. In some ways, we’ve become a society that’s more performative and we’re more about doing, or shall we say being seen doing, than we are about being. The things of home, the real human things that we are nurturing in the home, are things that tend to be more hidden. And a hidden life kind of grew out of fashion; a life of visible performance and function rose to the fore. And with that came a trend towards convenience to free up time for the performance. I think, there was a real switch to more convenience, fast food, just living your lives in ways that were full of shortcuts.

GL: Yes! And I wonder if that all has reached a tipping point, and now there’s sort of a zeitgeist against it. A burgeoning moment in which we’re being allowed to flourish again.

NM: I think you’re right. I think what we’re seeing now is the resurgence of more of the slow return to craft ways of domesticity. It is in reaction against the functionality and artificiality. People sense that is all fundamentally unsatisfying — it’s not as healthy, not as human. We are drawn back to the craft of domesticity. But even so, somehow we’re kind of missing the idea of rediscovering the beauty of the person who’s taking care of the home, the human who’s doing all of those things.

It is in reaction against the functionality and artificiality. People sense that is all fundamentally unsatisfying — it's not as healthy, not as human. We are drawn back to the craft of domesticity.

GL: How do you mean?

NM: I think the word “homemaker” always makes us cringe a little because it became reduced to a sort of dumbed-down servant role. It was given a cast that was very negative for a long time. There is a need to recover the true beautiful meaning of homemaker, one who makes a home. What could be more important for that? We need to articulate it, especially for women, and with a focus on women in all different ages and stages — so it’s not strictly just about stay-at-home mothers. Everyone we know really wants to nurture their home life. Men, women, single people, people with children, people without children, people whose children have gone and flown the coop, and people who are in the trenches with a bunch of little ones. All these people really care about these things, about making a home for their loved ones, about being a homemaker. So I think in our lives and reflections, we need to dig into that and what that connection is, as you said, why we’re more interested in that now, why society, in general, is more interested in that now, and what are the deeper meanings behind that and how do we think about and honor the people who are doing it.

GL. I used to really struggle to embrace that word too, “homemaker,” which now seems kind of crazy. It’s the biggest, most important thing, mothering and making a place for a family. Chesterton has a quote about that: “How can it be broad to be the same thing to everyone, and narrow to be everything to someone?”

But I remember a passage that really stood out to me from one of your books, taking up this question of being a homemaker and contrasting it with simply caring for our home. Saying something to the effect that there is a disconnect between loving our homes and recognizing the value of a loving homemaker. There’s a disconnect. I mean, people certainly could take pride in their homes, love their homes, love this craft stuff, but then that connection, this recognition of it existing in the relationship to being a human and homemaker — the understanding of that importance and real value might still not be present. It’s just sterile, just a page in a glossy magazine. What’s behind this? We aren’t connecting the dots.

NM: It’s a great question. I think that it’s kind of tied to the idea of the public life and the doing versus being. But ultimately it’s this distinction between understanding our purpose as being one of power versus being one of fruitfulness. For a long time, I think we have set up all of humanity on this axis of power. How can I gain power? How am I oppressed from having power? You know, this zero-sum game that really pits people against each other.

The interesting thing for us to understand is that we actually really are powerful. I am meaning women specifically, but all human beings are powerful. We can hurt others or we can help others; we can love or hate; we have immense abilities. But power is not our purpose, and I think the more we devolve into understanding our purpose in life as just getting and maintaining power, the more we set ourselves up for a lot of anxiety comparison. It’s an unsteady foundation.

There really is no reason to think of power as being our purpose. I think it’s just been drilled into us for a long time. I talked about that a lot in Awake Not Woke. But that shift into understanding our power, recognizing our purpose as really being one of service, love, fruitfulness, beauty: something that’s outside of ourselves. It really leads to the opposite of anxiety and comparison and all these other hard ways of being. It instead leads to sort of an ability to lose ourselves, to become engrossed in the project and the mission that we have in front of us and the beautiful things we can do right here and now. The nice thing about homemaking is that it’s something very tangible, and it is something that bears fruit. It’s like a garden: we’re planting seeds, receiving things, nurturing them — the people in our homes, the relationships.

It really leads to the opposite of anxiety and comparison and all these other hard ways of being. It instead leads to sort of an ability to lose ourselves, to become engrossed in the project and the mission that we have in front of us and the beautiful things we can do right here and now. The nice thing about homemaking is that it’s something very tangible, and it is something that bears fruit. It’s like a garden: we’re planting seeds, receiving things, nurturing them — the people in our homes, the relationships.

All these are slow ways of becoming more open to receiving other human beings into our lives and bringing something more beautiful into each other’s lives, in a way that is oriented around love rather than power. So I guess that’s the simple answer to your question, that shift from power to love, to service, to fruitfulness.

GL: That’s beautiful. That’s an absolutely wonderful response. Love over power. And for a homemaker, that love is not an abstraction. As an author, I can write an essay on love. Maybe I can write a book on love. I can have a philosophical debate about love. But ultimately that’s just an abstraction. When it comes to these people in this house and this daily task and this homemaking thing, it is so fleshed out — it is so tangible that it’s almost unrecognizable! So that concept of seeing love in the midst of the daily grind, being a homemaker, mothering in the midst of people full of needs and wants and weaknesses — that’s love.

[T]hat’s just an abstraction. When it comes to these people in this house and this daily task and this homemaking thing, it is so fleshed out — it is so tangible that it's almost unrecognizable!

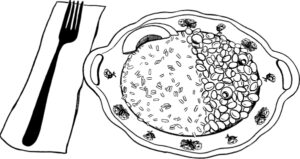

NM: Right! I think that in so many ways we’ve made the big things in life abstract. Love and hate have become abstractions. Homemaking creates an understanding that our love is called to be concrete. That’s what I think of when I think of “homemaking.” It’s food and decor and the comforts of a place — but it’s also the discomforts! It’s itchy; it’s bodies everywhere; it’s stitches when your toddler runs into a table. It’s all these things that are very bodily. It’s this connection to our humanity. I think we’ve lost that in the notion that love is an abstraction. But love is real and human, and love is hard work.

We have no problem contextualizing sacrifice, hardship, monotony, routine, and effort in the context of training for a marathon or a high-end career or, as you said, writing a dissertation or a book. There are all these things that we’re willing to do: hard, long hours that are brutal and difficult and challenging and exhausting for other causes. But somehow for the sake of our family life and our home life, we think that they’re beneath us.

GL: I remember somewhere you wrote that becoming a homemaker is like getting a doctorate in love. And I thought, oh my gosh, that is so beautiful and so contrary to our worldly understanding of what success looks like and what sort of the external stamp of approval looks like. And you know, nobody gets trophies for love — well, I suppose eternal life in heaven; that’s better than a trophy. But here on earth we just don’t get the attention for that. So I just adore that image. But anyway, it’s strange, this lack of perceived value.

NM: Yeah, it is a strange phenomenon. I surely don’t think it was common a couple of hundred years ago. Somehow it has snuck into our subconscious. I hear it again and again, how much women struggle with feeling like they’re wasting their time or their gifts — as though we’re squandering them by spending them on the people who are most important in our life, in the place where life actually happens.

And I relate to it certainly! It’s hard to leave grad school and then all of a sudden you’re a stay-at-home mom. And women are all in different situations and circumstances. But I think rediscovering the nobility, the fact that these things are worth the sacrifice — this rediscovery is critical. There are a lot of things you could be doing, but this is far more worthwhile. It’s going to take that sacrifice, that effort, that daily grind, that exhaustion. Just as we uphold and value it in other areas, we have to uphold it in our home life as well.

GL: So society somehow got off track in its understanding of the dignity and value of the home, the making of a home, and the maker of the home. I wonder when it started, what the root cause is.

NM: That’s a big question. I suppose you could trace the roots of it all the way to the Garden of Eden, but we probably don’t have time to go back that far. A convenient place to pinpoint it might be the Marxist movement. We crashed hard with Hegel and Karl Marx and all that followed. The Marxists reoriented us to understand a totally materialist worldview, where there’s nothing beyond the material that is real. Utility becomes a function of that worldview — that we are to be evaluated according to our usefulness, rather than according to some sort of intrinsic dignity or the inalienable worth of the human being.

And then it got kind of put on steroids with postmodernism. Tearing down meaning and grand narratives and really elevating that Marxist understanding of oppressor and oppressed. All human experience seen as a power struggle. And that truly became the goal, right? There was a desire for us to understand ourselves as beings who are defined by oppression, either by the way that we perpetrate it or by the way that we are victims of it.

There was a desire for us to understand ourselves as beings who are defined by oppression, either by the way that we perpetrate it or by the way that we are victims of it.

GL: And we see that played out in our relationship between men and women. Some natural differences in the way, let’s say, my husband and I experience life or even how we experience your book on the kitchen table, as I said – but taken and twisted into an orientation in which those differences instead of being complementary and beautiful must create a war between us.

NM: Yes. When everything is class warfare, I think for men and women this sense of differences creating tension became horribly heightened. Because once we believe that there is a power play at the very core of our relationship with each other, then everything becomes a struggle. What can we get at the other’s expense? There’s no harmony; there’s no ballet there! It really is just a dogfight. The Marxist movement redefined us and, I think, left us pretty miserable.

If we understand ourselves and our homes that way rather than understanding that we are called to be people of generosity, we immediately lose our way. Marxism is not a recipe for a harmonious and beautiful and joyful life. I think we’ve been sold a bill of goods for a long time. I don’t think we even recognize it as a society. Because it’s been transmitted to us through the culture, in these small ways, we’re absorbing a whole power and class-warfare ideology without even realizing it.

So we’re buying a t-shirt that says “girl power” or whatever. And it’s a good message in a certain context. Women have truly been treated unjustly in many times and places. But I would say that fact itself is an outgrowth of these very ideas of domination and materialism and power struggle. The same approach — domination and materialism and power struggle — from the other direction cannot now solve it. It’s not a simple story, of course; it’s complex, and there are a lot of factors going into that. But it’s these subtle messages that are packaged over and over again, and they really become hard to question.

But we have to question them. And I think that people are starting to question them, and that’s why people are looking for a more human way of living. A home life and family life and relation between the sexes that is more of that ballet and less of that battle.

GL: More dance and less dogfight.

NM: Yeah. This is why we’re returning to gardening and chickens and slow-cooked meals and knitting — all these things. If you clamp down the human spirit, it starts to ooze out in all these different ways! People want to find a way out of this suppression of their humanity. And so the more we see people expressing these desires, I think we find they’re all connected. It’s just a yearning to be human, to really live a human life. So I I see it as very promising and hopeful at this point.

GL: I love what you’re saying about homemaking as a response to the Marxist attack on humanity. And you just did an amazing job there in tracing those influences through history, and even just hearing you tell the story kind of makes me sad and feel heavy. I feel sort of like a machine myself as we’re talking through that, right? It’s so pervasive; I’m not really fully free of it yet. But homemaking as such an antidote! — in contrast to all of those trajectories.

And it’s universally available. Almost universally, at least — of course, we always pray for those who are homeless and try to help them — but most of us have within our reach the ability to do homemaking in one context or another. It’s caring and clothing and feeding and sheltering and loving people, with real intentionality. It’s spiritual; it’s an intangible; it’s kind of a relational thing, but it also has this very concrete and enfleshed incarnational side. Which appeals to us humans, both physical and spiritual. And again, that really is a universal. It’s not just a mother thing. Father is part of the home. A single person has a home. A religious community has a home. And I see the capacity in front of all of us to make our home lives an antidote or a response to all those things you’re talking about. But then, given that universality, I wonder too, what is the distinctly feminine aspect of it supposed to be? I mean, honestly, I’m not very good at cooking, and there are many times when I feel like it’s a skill that I just can’t seem to master. What is the balance?

NM: I actually relate to that. I’m not a natural cook. My husband is far better at cooking than I am. Part of that is maybe just the art of discovering your gifts and leaning into those. But no, I think what you said — there’s imagery here about receptivity that plays into the gardening metaphor. Historically, in romance languages in particular, the things that are vessels tend to be feminine words, like the nave and the ships; the Church is a her; even ovens in certain languages are feminine. And it’s not strictly that these represent virtues that only women should inculcate. As you say, we’re supposed to have a mother and father. There’s a masculine and feminine to all these things for a reason because they’re two expressions of one being when you know God and God’s love. Still, they are distinct expressions; he made us male and female. And this idea of vessel I think is really fascinating in that, for us as women.

There’s something about relationships that is actually really bringing someone into the vessel of our life, of our self. That can be through our thoughts or by bringing them into our prayer life — or more literally, as in the case of children, by bringing them literally into our bodies as mothers. We are vessles. And it’s all manifest by bringing people into our homes.

GL: Is there tension for you between your work as a writer and as a homemaker?

NM: Ideally not? So yeah, I am often working in the world of ideas, trying to defend ground. I tend to write things that are kind of on the defensive. Defending mercy for, instance — one of those unsung words today. At some point, I started seeing in more news stories that there was sort of an increasing mercilessness. And that became really fascinating and concerning to me —why is there this death of mercy? I write about it in Awake. But how ironic if I were to write about it without mercy! The physical grounds me, keeps me balanced. I really want to be clear, even to myself, that I am not writing to be polemical. I really want to be motivated out of love and desire for people to be happy and live happy lives.

Tenderness is also one of those unsung words. It just sounds like something sort of sappy or sentimental. But when we think about it in medical terms, tenderness, something that’s tender, is something that requires interaction with in order to be understood. So you don’t know that something is tender until you press upon it. And I love that as a metaphor for just the art of doing relationships well— that we have to be receptive and actually know another person; touching until you feel. We have to be interacting with another person in order to really know them and to be some part of healing for them and them for us.

Tenderness is also one of those unsung words. It just sounds like something sort of sappy or sentimental. But when we think about it in medical terms, tenderness, something that’s tender, is something that requires interaction with in order to be understood. So you don’t know that something is tender until you press upon it. And I love that as a metaphor for just the art of doing relationships well— that we have to be receptive and actually know another person; touching until you feel. We have to be interacting with another person in order to really know them and to be some part of healing for them and them for us.

That takes a real patience. It’s something that’s not instantaneous; it’s different than just “read this thing I wrote.” It’s something that’s slow, and I think that our homes are perfect vessels for that. We can’t always get someone to go to church with us, or be affected by something we write, but we can usually get someone to come over for dinner or for a cup of coffee. My husband and I tend to be very social people and that idea for us has really been transformative because it made us understand that the friendships that we enjoy fostering already are actually something that can be united to our faith in a really powerful way. That doesn’t necessarily mean, or need, results today or tomorrow or the next month. But there is a dignity in just loving people, not for the sake of what you’re trying to convince them of or for the sake of being right, but just for the sake of befriending people and sharing your lives with one another. We can learn from them and they can learn from us. That is an aspect of evangelization, of the “new evangelization,” that I think is underserved and overlooked.

GL: So we have this concept of a new evangelization within a re-paganized society, and also this term the “feminine genius.” They’re kind of being articulated at the same time, put out there over the past forty years or so, but not fully defined. And maybe they are more deeply connected than we realize. It’s sort of the project of our generation to figure out what that means and what that looks like. And I just feel like your work is making an amazing contribution to exploring that and to giving vision to that and to giving words and vocabulary to that and giving images to that and — and it’s lovely.

NM: Thank you so much. That means a lot to hear. And yes, I think you’re right: it’s the project for our generation to define, or to recover. It’s our moment in salvation history. Carrie [co-author of Theology of Home] came up with the phrase “theology of home” one day, and it just occurred to her that all we really want to do is go home, you know? We want to be home, which ultimately means heaven. Home has sort of this quality that’s outside of time. Home is full of memories and nostalgia, but it’s also looking to the future. We’re looking for our “forever home” — that’s become a trite real estate phrase, but I think it’s really something true. And there must be an incarnational aspect of all that, which has been too easily dismissed and dehumanized, but which we can recapture. There is longing and belonging in all these things, and a need for permanence that points beyond the temporal.

Mrs. Noelle Mering is the author of Awake, Not Woke, a coauthor of three Theology of Home books, and an editor of TheologyOfHome.com. She also writes about culture, politics, and religion for many major news outlets. She and her husband have six children and live in California.

Mrs. Gina Loehr is the author of five books and the mother of six children. She is a columnist for Hearth & Field, and a frequent speaker and guest on national television and radio programs. She writes from her home in Wisconsin, which doubles as the Loehr dairy — a century-old family farm.

[The above conversation has been edited for flow and length.]