All Cooped Up

Mrs. Gina Loehr

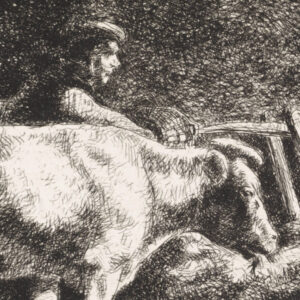

Ten years after I moved to my husband’s dairy farm, I finally got a horse. This matter had been a point of playful contention between Joe and me for quite a while. His animal of choice has always been the cow. She is productive and predictable. Feed her, and she will feed you. Joe either learned or inherited the skill of caring for these bovine creatures with a polished professional flourish. He is not a generic animal guy — he is a cow guy.

He also either learned or inherited an idea held by many farmers of his ilk regarding the value of the equine species. Namely: since the advent of tractors, a horse is little more than a “hay burner.” Feed him, and he will stand around and eat. Joe just didn’t think getting a horse made any sense.

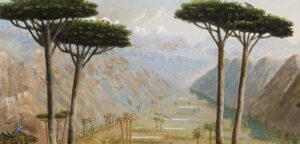

I, on the other hand, argued in favor of the aesthetic value of a stallion galloping nobly across our fields and trails. The elegance and grandeur of a horse add beauty and sophistication to rural existence. The capacity for bonding and the service of providing the sport of riding make a contribution that goes beyond the purely practical or utilitarian. Yes, he may be costly compared to a cow, but the horse is not without his merits, abstract though they may be.

The elegance and grandeur of a horse add beauty and sophistication to rural existence.

So, it took a decade, but Joe finally turned around on the matter (out of love for me, not of horses) and we adopted a twenty-one year old arthritic Tennessee Walker named Zip. I met him while volunteering at an equine sanctuary nearby, and my oldest daughter and I both loved him at first sight. He was calm and stately, and he needed a home. So Joe graciously sacrificed part of a hayfield to the horse pasture and built the fence in a weekend, and Zip moved in.

The finicky old creature proceeded to go on self-destruct. He wouldn’t eat. He wouldn’t drink, even in the sweltering end-of-summer humidity. He stood at attention in the pasture for three days straight without blinking. We called the sanctuary. They sent out a companion mare (free of charge) to cheer him up and help him adjust. Thus, Star, the-nine-year-old arthritic Paint joined the team.

But Zip had lost his zip, and it looked as though he was on his way to R.I.P. So he went back from whence he came, while Star stayed. For three weeks. Until the day she kicked my seven-year-old across the pasture as punishment for grooming near her sore hip.

We hadn’t realized just how sore her hip was until that unexpected moment. The tactful hoof trimmer who came to the farm had hinted gently to us novice horse owners, “I don’t mean to be the bearer of bad news, but this animal has a bad leg and will never be rideable.” The sanctuary folks had led us to believe otherwise, that she just needed time and training. The escapade lasted exactly one month. I was relieved to be free of the stress, but my children cried as we watched Zip leave, and then when Star went away more tears were shed. The children’s spontaneous response to the unfortunate affair was to set up a horse fund.

We hadn’t realized just how sore her hip was until that unexpected moment. The tactful hoof trimmer who came to the farm had hinted gently to us novice horse owners, “I don’t mean to be the bearer of bad news, but this animal has a bad leg and will never be rideable.” The sanctuary folks had led us to believe otherwise, that she just needed time and training. The escapade lasted exactly one month. I was relieved to be free of the stress, but my children cried as we watched Zip leave, and then when Star went away more tears were shed. The children’s spontaneous response to the unfortunate affair was to set up a horse fund.

They collected nickels and dimes over the next few months and placed them inside a glass milk bottle on the shelf. Their plan (unapproved by their mother, who had humbly abandoned her abstract romanticism) was to save enough money to buy a young, healthy horse so we wouldn’t have a repeat of the debacle with the rescue animals. After not quite a year, the kids had pooled about two hundred and fifty dollars. It looked as though getting a (nice) horse was still a long way off. So my nine-year-old son got an idea and made a proposal.

Chickens.

“Let’s get chickens instead,” he urged his sisters. The reasoning? We can get chickens right away because they’re cheap. And they will lay eggs that we can sell. So the project will produce a profit and in the end be much more worthwhile than saving for years to get a horse that will only cost us more money. He’s his father’s son, that one. With this development, all equine dreams were finally put to rest, and my children turned their efforts toward poultry.

With this development, all equine dreams were finally put to rest, and my children turned their efforts toward poultry.

I had never particularly wanted chickens. I couldn’t make an argument for their elegance or sophistication if I tried. I have not often imagined myself riding one into the sunset. But I had to admire my son’s reasoning. And since it managed to sway his sisters, Joe and I told the kids they could take on a chicken project if they wanted to, but it had to be their project from start to finish.

Before we knew it, the kiddos had put two hundred of their dollars towards a build-your-own chicken coop kit complete with a nesting box, a roosting spot, a ramp down to an open area and a charming red door that serves no purpose whatsoever. They assembled it in the front yard and set it up on the back deck with a waterer and a feeder to boot.

Now, they just needed chicks. A little research and a few phone calls later, the order was placed. Come mid-August, the children could not contain their glee when we drove to the feed mill to pick up their White Leghorn baby birds.

The three-dollar pullets came home in a cardboard box, and their owners pampered and tended to them with great devotion. Joe helped set up a heat lamp and a comfy bedding area in the nesting box and the kids took over on feeding, watering, and bedding the little fuzzballs. A month later, one flew the coop, literally. But the others grew well and by January sixteenth, the first egg appeared along with great rejoicing from the little Loehr farmers.It took me a while to get comfortable handling those fresh white orbs. They came to my door in a child’s hand, always straight from a pile of straw and sometimes still warm. Instead of finding a dozen pristine shells of consistent size sitting in their tidy compartments in a store-bought egg carton, I had to wash off little bits of this and that, one egg at a time, usually three times a day.

The three-dollar pullets came home in a cardboard box, and their owners pampered and tended to them with great devotion. Joe helped set up a heat lamp and a comfy bedding area in the nesting box and the kids took over on feeding, watering, and bedding the little fuzzballs. A month later, one flew the coop, literally. But the others grew well and by January sixteenth, the first egg appeared along with great rejoicing from the little Loehr farmers.It took me a while to get comfortable handling those fresh white orbs. They came to my door in a child’s hand, always straight from a pile of straw and sometimes still warm. Instead of finding a dozen pristine shells of consistent size sitting in their tidy compartments in a store-bought egg carton, I had to wash off little bits of this and that, one egg at a time, usually three times a day.

For the first few weeks, when I cracked the eggs, I was always afraid I would see something weird inside — blood or beak or who knows what. But that never happened, and the more I got used to it, the less strange it all felt.

Little did we know when this all began that within two months of the first egg we would be living under safer-at-home orders and that obtaining the most basic groceries would become a challenge. As I fried eggs and made omelets and baked cakes during those first bizarre weeks of COVID quarantine, all without setting foot in a store, I could not help but feel a deep sense of pleasure and gratitude that my children had decided to raise chickens.

We were now cooped up at the farm, so to speak, but between the eggs and the milk and the beef and the pork and the canned beets and beans and the homemade yogurt, we had enough to get by. It was an incredibly satisfying and comforting feeling. Come what may — coronavirus or otherwise — we were not going to go hungry.

Horses (like dogs, lizards, cats) cannot provide this kind of primordial security. The guarantee that our family has the means to produce its own food is a liberating reality. Animals surely offer companionship to the human race and beauty to the world. And some animals do so more than others; I have not yet noticed our chickens galloping nobly across our fields and trails. (Though they’re actually rather lovable in their funny way.) But certain animals are simply better equipped than others to offer us the invaluable security of self-reliance.

You don’t have to be an experienced farmer to take a step in the direction of establishing this security for yourself. If a group of kids can figure out how to get fresh eggs on their breakfast table every day, you can do it too.