Finance to Farming

A Discussion of Risk & Reward

With Ross McKnight

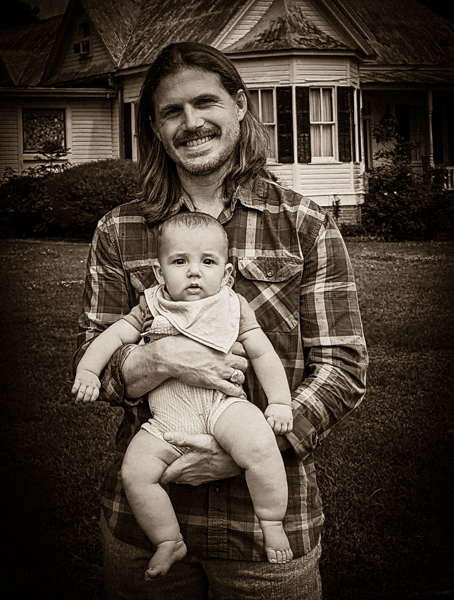

Hearth & Field had the chance to connect with Mr. Ross McKnight — husband, father, Louisiana farmer, and former finance professional. We enjoyed a wide-ranging conversation, covering matters from technology to stocks and bonds to animal feed to French culture.

Hearth & Field: Before becoming a farmer, you worked in finance. Can you tell us about that first career? What motivated the change?

Mr. Ross McKnight: We’re opening a tremendous can of worms here, but I’ll do my best to keep most of the wrigglers contained.

Of the good things I learned, the basics of running a business certainly take the cake. Working in a business that requires so many relationships in order to establish viability and resiliency, communication skills were important, as well as being consistent, reliable, and accessible. My studies as an English major were certainly put to use, if not the best possible use.

Material success in that industry requires great personal drive. Having young children and a wife at home provided a particularly good motivation for avoiding failure in my case. And I ended up doing “very well for myself” (as the saying goes).

The field is fraught with pits and holes of every sort, however, and the need to make decisions that render one — despite precautions and despite the industry narrative — consistently in scenarios that could be considered conflicts of interest. This wasn’t particularly comfortable or healthy. In any case, between a goal I had set early on and the onset of severe health complications, I was destined to leave the finance industry and its worldly triumphs.

H&F: What was that goal?

Mr. McKnight: To start a farm three years from the date I was hired on at the firm. (I even expressed that in the interview.) But the final push out the door resulted from a battle with an autoimmune disease. In 2019, I underwent a total colectomy and related procedures, all rather unpleasant. I remember not a lot from this period of my life (probably due to the general anesthesia and all of the pharmaceuticals), but I do remember lying in the hospital bed and making an agreement with our friends from Toulouse to start a foie gras farm and call it “Backwater Foie Gras.”

After leaving the hospital, I was unable to do much, but I managed to raise and fatten a few ducks, and eventually we were blessed with beautiful foie gras. At this point we knew we could — knew we must, for the sake of our family and for the sake of living a bonafide life — make the transition to farming for a living. Or rather, it was now or never. We plowed ahead and began looking for land.

H&F: And you found land, while still juggling health challenges?

Mr. McKnight: We found land. We found more than that. We bought a home-place with my parents that provided two dwellings, along with a barn and good infrastructure to make a start. Despite the failure of my first surgeries and the ordeal of repeatedly traveling to have them revised, we are still here, farming — by God’s most generous bestowal of grace.

H&F: It’s a big change from what you’d been doing.

Mr. McKnight: Yes! But it’s not an unheard-of scenario: the man who has a brush with mortality and decides to make major changes to his life. Despite my delusions to the contrary, I am just a regular, old human being.

H&F: It’s not unheard of, but it’s always striking to hear of. And this particular sort of change seems to be something we hear more of in recent years. Someone leaves a desk job, a digital job, a job in finance or technology or whatever the “information economy” is, and becomes a farmer or carpenter or butcher — a movement from abstract, derivative things to more direct realities. Do you think this is a sort of zeitgeist moving through the world right now?

H&F: It’s not unheard of, but it’s always striking to hear of. And this particular sort of change seems to be something we hear more of in recent years. Someone leaves a desk job, a digital job, a job in finance or technology or whatever the “information economy” is, and becomes a farmer or carpenter or butcher — a movement from abstract, derivative things to more direct realities. Do you think this is a sort of zeitgeist moving through the world right now?

Mr. McKnight: I couldn’t say whether it is the zeitgeist or a small, anecdotal phenomenon, although my opinion may develop over time.

I’ve heard that there is a movement away from smartphones amongst Gen Z. The appearance of the intentionally-dumb-phone is not negligible. We moderns, however, seem to have locked ourselves up with technology and lost the key. I recently attempted to transition to using a dumb phone and found that it actually made my life more complicated because it did not eliminate the need for a tablet for managing business matters. The very function of economies now rests upon silicon and solder, and I’m not certain there’s a way for most of us personally to detach from it.

Farming (or butchery, carpentry, et cetera) is not a viable escape — nor is “escape” itself viable — from the exigencies of modern life, but it does place one for extended periods of time in contact with simple reality. For example, a pork must be broken down into various cuts and preserved once the pig has been slaughtered, and the clock starts ticking with the kill-shot. The investment in the livestock and the family’s requirement for nutrition hang upon the thread that runs through the whole process of turning a live animal into food. There is real risk, and there is real reward. I think there is a significant movement of families toward lifestyles that involve direct (not indirect as through a screen) contact with real risk and with real reward.

H&F: But even if less “direct,” the world you left also has risk and reward. Maybe the rewards of farming feel more fullfilling, but let’s compare the risks. In your experience, having spent time in both the digital corridors of centralized U.S. finance and in distributist, small-scale, agricultural business, does one realm seem more resilient than the other?

Mr. McKnight: Indisputably, the digital corridors are the least resilient. The silliness of numbers dancing up and down on a screen is surpassed only by our determination to assign value to them. C’est n’importe quoi! But imagine if all of the dollars and cents invested in stocks, bonds, and mutual funds over the last fifty years were instead invested in the respective communities from which they were extracted!

The silliness of numbers dancing up and down on a screen is surpassed only by our determination to assign value to them.

What is risk mitigated by, after all? Currency? No. What frivolous nonsense. Currency is “worth” something today and best used as fuel for the fire tomorrow. Risk is mitigated by the good will of men. The risk of building bonds between family, neighbors, and friends is the pain of disappointment, loss, or betrayal. But I would say with a great deal of confidence that we would all prefer to be hurt by human beings we know (who can be redeemed) and lean upon the others who are faithful than be hurt by the Fed or the central banks. Who will be there when we’ve lost all we squirreled away of our time and our love and our labor and our dedication into ETFs and REITs because some oligarchs no longer found the current financial system convenient?

The risk of buying into the financial scheme is our humanity, our virtue — and perhaps our souls. The risk of investing in our communities is becoming truly human, in both our strengths and our weaknesses.

H&F: So tell us a little more about your farm.

Mr. McKnight: There are two purposes to our farm at the moment: to provide the highest quality foods for our family and to produce high quality meat products for the people of our region.  To that end, we maintain a flock of laying hens, who supply breakfast through a curious process each morning. Pigs — such as the two Hampshires we have in one of our barns — we raise for members of our PMA (Private Membership Association). I slaughter and butcher the pigs here at the farm. Currently, we have four Idaho Pasture Pigs out on — you guessed it — pasture, and I am excited to examine the carcass quality once they go to slaughter, which should be soon.

To that end, we maintain a flock of laying hens, who supply breakfast through a curious process each morning. Pigs — such as the two Hampshires we have in one of our barns — we raise for members of our PMA (Private Membership Association). I slaughter and butcher the pigs here at the farm. Currently, we have four Idaho Pasture Pigs out on — you guessed it — pasture, and I am excited to examine the carcass quality once they go to slaughter, which should be soon.

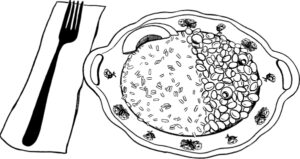

We also maintain a small flock of (horribly recalcitrant) Gulf Coast Native Sheep for our personal lamb requirements, and my wife milks our Jersey-Guernsey-cross dairy cow each day. Fresh, raw milk turns into cheese, cream, butter, et cetera for the home kitchen. Lastly, a small herd of rabbits gives us the opportunity for the odd Lapin å la Moutarde.

Raising the most beautiful meat we can for our family is certainly a priority. I get tired at times, but I dare to make the claim that I’ve seen glimpses of God’s goodness that can only be revealed in the chops of a well-fattened pork.

The production of foie gras allows us to approximate making a living with the land because we sit squarely in a niche of the market. I say “approximate,” because, as long as there are no major hiccups, we can do decently for ourselves, but weather and other volatile factors beyond our control have major effects on our bottom line. If we’re patient, however, these risks can teach us abandonment to Divine Providence.

H&F: What people or schools of thought have influenced your approach to all of this?

Mr. McKnight: We are profoundly influenced by Brandon Sheard of Farmstead Meatsmith and his traditional, old-world approach to animal husbandry, slaughter, and butchery. I would recommend his programs to anyone interested in farming on the domestic scale. I owe much of my acquired knowledge and skill to Brandon’s inspiring perspectives on seasonality, meat curing and preservation, and the liturgy of life.

As to schools of thought, I’m not entirely convinced by the “Regenerative Agriculture” movement. While many of its proposed methods are good, some would require total neglect of sleep in order to execute, and much of the orthodoxy propagated by the talking heads (usually talking through a screen) of the movement is, in fact, impractical to such a degree as to make its application on a small scale completely impossible.

An example: I have found that our regional infrastructure supporting the manufacture and distribution of Non-GMO animal feeds is weak, and, in my case, utterly unreliable. Last year, we took the risk of completely changing our feed program to utilize Non-GMO products, and the feed would arrive in poor state, leading to higher mortality rates amongst our livestock. We cannot make a living if our ducks are dying on pasture from feed contamination. It would be irresponsible (and actually insane) for me to feed my ducks a product that provides insufficient nutrition or is actually fatal. So it’s not a black-and-white issue, but rather a case-by-case consideration.

H&F: What sorts of improvements have you made to your property to support what you’re doing?

Mr. McKnight: When we purchased it, the grass was kept excruciatingly short. What this meant for us was that the land needed rehabilitation due to the effects of the sun on earth that is not covered by longer, healthier grass-blades, along with the lack of organic matter in the soil. But I’m quite certain we will be working on the project of improving our pastures indefinitely.

To convert what was essentially a large family home-place that also featured a barn containing a workshop, we cleared out the lean-to of said barn and built pens.  We also assembled mobile duck-houses, emptied a metal storage building and prepared it as a location to house very young birds, and constructed a small processing plant (state-monitored) within the existing workshop. And, a year or so after moving on-site, we removed innumerable shards of glass from an old, derelict greenhouse and remodeled it into another barn.

We also assembled mobile duck-houses, emptied a metal storage building and prepared it as a location to house very young birds, and constructed a small processing plant (state-monitored) within the existing workshop. And, a year or so after moving on-site, we removed innumerable shards of glass from an old, derelict greenhouse and remodeled it into another barn.

H&F: You mentioned having a degree in English. Much of the current fascination with restoration of agrarian lifestyle exists in an Anglophile-Anglophone orbit. We read British authors, learn about English land movements, obsess about Victorian farms. Meanwhile, you’re carrying forward French agricultural and culinary traditions, and you live in a historically French area. What can we learn here? Are there French influences on farming, family, and culture that the English-speaking world ought to be more attuned to?

Mr. McKnight: I think the French mindset could best be summed up in the statement “Let’s get down to the business of making it good.”

I share your observation that there is a great deal of romanticism and abstraction that occurs in the Anglo-sphere’s (often nostalgic) reflection on “the old ways.” I enjoy the thought-project as much as the next romantic, but when it comes down to it, you have to be uncommonly good at what you’re doing if you want to survive as a small-scale farmer in today’s upside-down food-production model, and even then I’m not sure material success is possible.

I think the French mindset could best be summed up in the statement “Let’s get down to the business of making it good.”

My impression is that, for the French, the tradition is still alive, and so there’s no need to sit around musing about it. Instead, let’s talk about the key points required in creating a quality product: impeccable grain, proper cooking temperatures, good pastures, water access for the birds, when to administer a feeding and when to withhold.

The romanticism (or perhaps just the sincere and thorough, educated appreciation), on the other hand, can be detected in the French consumer of duck products (I know this because French visitors and expats have a remarkable knack for finding out about my existence). This appreciation that comes from frequent contact with goods that are authentically themselves is something not so easily attained by the American consumer, because everything in our foodscape is a lie. In France, the lie is at least less prevalent.

H&F: You and your wife have been on quite a profound journey, then. She must be a singular sort of person. Can you tell us about her? What has her perspective and involvement been in all of this?

Mr. McKnight: You are correct in guessing that my wife, Dorothy, is a singular sort of person. I’d go so far as to say she is a remarkable woman. I’d even venture to say that she is going to be a saint.

From being my caretaker and nurse (and also handling all of the household duties) while I was disabled to fattening ducks while I was recovering from surgery, she’s always been willing to bear difficult situations with much grace and patience. These days, she manages daily to milk our cow, clean the milk-machine, and filter the milk and store it — alongside teaching and caring for our five children.

Strangely enough, we both dreamed of this life for many years (without knowing the least bit about what we were getting ourselves into). We’ve both learned to take significant satisfaction in the manner in which food reaches our serving dishes under our combined influence — her role in that respect being the management of the dairy and vegetables, mine being the management of the meat animals.

The overarching theme for both of us, is at least to attempt the pursuit of continual conversion of life. Farming is a penance. It is good. It is gratifying. But it is most certainly a penance whereby we, when we’re at our best, attempt to “work out our salvation in fear and trembling.”

We’ve both had to sacrifice much over the years, but I would venture to say that Dorothy in particular has renounced herself and taken up her cross, and not in a mournful or dour-faced way, but with love and with joy.

H&F: How do these things we’ve been discussing — farming, French culture and language, contact with reality — influence the way you and Dorothy rear and homeschool your children? What have you found to be effective as you try to pass it all on?

Mr. McKnight: It turns out that children benefit as much as we do from contact with the real substance of life. Our children are frequent witnesses to the entire lifecycle of our animals, from piglet to pork-chop, and they’re now very familiar with the sentiments that accompany that experience. They’re capable of having affection for animals that they know will become food, and they understand why this is necessary.

Encountering the saddening requirement of taking animal lives in order to sustain human lives is an indispensable intellectual foundation. Our lives have a heavy and consistent cost, and acknowledging this then demands an explanation, an explanation provided with a flourish by the Catholic intellectual tradition, which we are passing on to our children.

The transmission of Louisiana culture must certainly be more intentional in this age and is therefore more burdensome, but my children pray the Rosary in French with me, and they are learning (slowly, and that’s my fault) to speak and understand the language. To that end, music is extremely effective, I find: if I can get them to sing “Tit Galop Pour Mamou,” then they’re authentically engaging the language without the laborious connotations of “education” crossing their minds. I’d submit that the same is true of prayer, and this is the idea of “effective use” — the language can’t be something obtained and executed in abstraction if it’s going to take hold in the memory. It has to, again, take part in real risk and real reward (for example, when I’ve required my children to use French at the dinner table to ask for something that they want passed to them).

Brandon Sheard often uses the phrase “failure to transmit” to describe the gap in knowledge of culture, cuisine, farming, religion, et cetera between ourselves and our great-grandparents. Dorothy and I are determined to do what we can to suture that wound and tend it. The farming lifestyle itself imparts so much by necessity: we can’t really get away from transmitting to our children the knowledge we are gaining.

[The above conversation has been edited for flow and length.]

You can learn more about Mr. McKnight’s farm and philosophy at BackwaterFoieGras.com