Home Fires Burning

Mrs. Libby O'Neill

In this darkest and coldest season of the year, when nature bares her teeth most clearly, our obsession with heat is unsurprising — both as an antidote to winter and a reminder that it won’t last forever. We heat our homes, our cars, our seats, steering wheels, and blankets. But while this fixation is, I suspect, much the same as it has been for humans throughout history, it is shocking to realize how comparatively little effort our warmth requires of us as compared to our not-so-long-ago ancestors. We flip a switch, push a button, turn a dial, and there it is. To be fair, that push of the button requires more from our bank accounts each day, but the work, time, and attention paid to heating our homes are almost nonexistent. We’re no longer chained to our woodpiles throughout the fall, splitting and stacking logs to ensure our families stay warm till spring. We spend our summers much like Aesop’s fabled grasshopper, for whom winter was not to be considered until it was upon him.

The benefits of this approach are obvious. But for over a decade now, we have heated our little home almost entirely by wood-burning stove. And this method has a list of drawbacks as long as my arm. The sourcing of wood, the splitting and the storing of it, the constant hauling, and the mess it makes. The bother of building a fire each morning, of feeding and watching it, of knowing that if, left unattended for too long, our house will gather the chill we have fought so hard to fend off—these considerations illustrate just what a waste of time and effort all this work must be when our home could be heated so much more conveniently.

But, as with so many things, the most important considerations don’t fit neatly on the list of pros and cons. And that list reveals a working assumption that rarely undergoes closer examination. The designation of all that we would consider “work” as a reason not to undertake a venture, belies a pernicious belief we hold somewhat dear — that work itself is an evil. A necessary evil perhaps, but certainly one to be avoided when possible and kept to a minimum always. The industrial and digital revolutions, in turn, have undoubtedly been huge leaps in the progress of mankind, because of the time they have freed up for us to spend on so many other things far more worthy of our attention than such banal considerations as finding food and shelter. Whether our use of all that free time bears witness to such a theory is up for debate. This negative view of work is a self-fulfilling prophecy; that which we view as drudgery will almost certainly become such. But a job well done brings a satisfaction that needs no defense. Knowing we create or provide something of value is core to our well-being. Higher still than cheerful competence or confidence is the work done willingly for love’s sake. What if, when we circumvent all the work that goes into meeting our daily needs, we also lose an opportunity to love one another?

But, as with so many things, the most important considerations don’t fit neatly on the list of pros and cons. And that list reveals a working assumption that rarely undergoes closer examination. The designation of all that we would consider “work” as a reason not to undertake a venture, belies a pernicious belief we hold somewhat dear — that work itself is an evil. A necessary evil perhaps, but certainly one to be avoided when possible and kept to a minimum always. The industrial and digital revolutions, in turn, have undoubtedly been huge leaps in the progress of mankind, because of the time they have freed up for us to spend on so many other things far more worthy of our attention than such banal considerations as finding food and shelter. Whether our use of all that free time bears witness to such a theory is up for debate. This negative view of work is a self-fulfilling prophecy; that which we view as drudgery will almost certainly become such. But a job well done brings a satisfaction that needs no defense. Knowing we create or provide something of value is core to our well-being. Higher still than cheerful competence or confidence is the work done willingly for love’s sake. What if, when we circumvent all the work that goes into meeting our daily needs, we also lose an opportunity to love one another?

What if, when we circumvent all the work that goes into meeting our daily needs, we also lose an opportunity to love one another?

In the heavy heat of August, in between animal auctions at the county fair, my husband starts to shore up our wood supply for the winter. The truckloads of tree trunks start rolling in, forming enormous piles by the woodshed. At a time of year when the younger kids are tempted to remain in a state of sedentary boredom, these log piles make for an irresistible playground. After the sourcing comes the splitting. Even the preschoolers help, armed with headphones to dull the sound of the wood splitter. They take turns pulling the lever on the machinery, watching it neatly slice each log into its parts, and carrying the pieces to their temporary home in the woodshed. No self-esteem workbook in the world speaks as loudly and irrefutably as a neatly stacked pile of logs. If we want to protect our children from the quiet desperation of uselessness, it falls on our shoulders to give them something useful to do. No trophy can replace the knowledge that they have served their family in a real way.

While the help from the older children is true service, the help from the younger children is an act of both patience and love on the part of their father, who gives them the time spent with him and gives me, his wife, the time spent without them. By the time we re-familarize ourselves with frost, most of the outdoor chores have been put to bed for the year. But the bringing in of the wood each evening calls the family back into service, as my husband heads out into the cold for the next day’s load, and the kids bring to the fireplace whatever they can carry.

While the help from the older children is true service, the help from the younger children is an act of both patience and love on the part of their father, who gives them the time spent with him and gives me, his wife, the time spent without them. By the time we re-familarize ourselves with frost, most of the outdoor chores have been put to bed for the year. But the bringing in of the wood each evening calls the family back into service, as my husband heads out into the cold for the next day’s load, and the kids bring to the fireplace whatever they can carry.

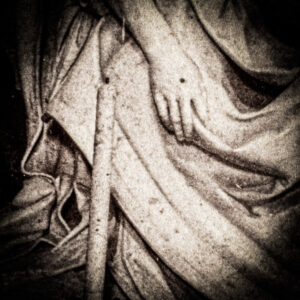

In the black, cold, morning, their father rises before anyone in the house. While we rest warm in our beds, he builds the day’s fire with the wood he has prepared, in so many steps, for the day’s heat. When I shake the school-goers awake, they ask, often before their eyes are even open, “Is there a fire?” One by one, in their stiff morning stupor, they stumble downstairs and gather by the glowing hearth, hoarding its glorious heat like misers. Having had their consciousness rekindled, they go about their days, carrying that warmth within.

One by one, in their stiff morning stupor, they stumble downstairs and gather by the glowing hearth, hoarding its glorious heat like misers.

Waking in the morning to the scent of smoky oak and the unspoken knowledge that someone who loves us has risen early into the dark for our sake protects us from the indifferent chill of a frosty morning and creates a home that is less like an incubator and more like a womb. It is not an impersonal heat. It is a physical experience of love, much like the enjoyment of a meal prepared for us by someone dear. I don’t expect to ever be wealthy, but in the quiet glow of a fire made by the man who loves me, I am rich.

Without the woodstove, my husband could sleep fifteen minutes later each morning. I wouldn’t have to vacuum nearly as much. And we could leave our home all day without a second thought. But what if these so-called “basic” needs of ours are more complex than they seem? Maybe it’s not just the daily bread that we need, but the daily baking as well. In our haste to bypass the process for the product, we may be leaving more than aggravation behind.

Our homes may be comfortable enough with constant central air, but “leave the thermostat on” doesn’t mean to us what “keep the home fires burning” does. And for good reason. The latter requires being attuned and attentive. It prioritizes the heart of the home, and in it there is a someone working to create comfort for his family. When it comes to getting needs met, our cultural insistence on efficiency prescribes eradicating this someone in favor of something, replacing this attentive affection with unattended automation. I think we can do no better than to be that someone. For while we may have become comfortable with a life that involves precious little physical work, we cannot make our lives a labor of love without any labor. And the real waste of time is doing anything else.