—Ink and Echoes—

The Philosophy of Gratitude

G.K. Chesterton

1903

I received a little while ago a letter, to which no name or address was attached, which touched me beyond expression. A great deal of it was too personal to treat of here, and for this reason especially I regret the concealment of its origin. But the more generally discussable part concerned itself chiefly with a query as to my meaning when I said in this paper something to this effect: ‘No one can be miserable who has known anything worth being miserable about’. The remark was written as remarks in daily papers ought, in my opinion, to be written, in a wild moment; but it happens, nevertheless, to be more or less true. What I meant was that our attitude towards existence, if we have suffered deprivation, must always be conditioned by the fact that deprivation implies that existence has given to us something of immense value. To say that we have lost in the lottery of existence is to say that we have gained; for existence gives us our money beforehand. It is quite impossible to imagine ourselves as really calling, as Huxley expressed it, the Cosmos to the bar.  Let me endeavor to indicate by a kind of apologue or parallel what the trial of the Cosmos would really be. A white-haired, ragged man is convicted of having stolen a handkerchief from an old gentleman in the street, and is examined before a judge. Suppose he is convicted. And suppose after he is convicted he is able to say blandly and with unimpeachable argument, ‘It was my handkerchief’. That is the position of God or Nature, or what you will. Suppose, again, that the judge and the Court are in some doubt about this reply. The man says, still very humbly, ‘It was my handkerchief; I made it’. ‘Made it’, the judge will say, ‘what did you make it out of?’ ‘Out of nothing’, replies the prisoner, and waves his hand. Sixty handkerchiefs flutter down out of the empty air. The judge is startled, and looks keenly at the meek prisoner; nevertheless he continues: ‘You may have made the handkerchief (though in this somewhat irregular way), and so far, of course, it may be yours. All the same you seized it from this old gentleman’, The prisoner coughs slightly and looks embarrassed. ‘The fact is’, he says, ‘the fact is, I made the old gentleman, too’, ‘What did I hear you observe?’ inquires the judge, with deadly placidity, ‘made the what?’ ‘Made the old gentleman’, rejoins the prisoner. ‘I can make sixty more if you like’. He waves his hand. Instead of one old gentleman at the prosecutor’s post, looking justly indignant, there are immediately sixty old gentlemen exactly alike in a row, all looking justly indignant. The judge confers with the clerk and the foreman of the jury; the incident is one for which it is difficult for the moment to find a precedent. At length the judge says, ‘You certainly seem to have some claims over the prosecutor, having produced him out of space in a somewhat careless way, but your offence against the Court itself, your demeanour towards myself – ‘ ‘I’m really terribly sorry’, says the prisoner, blushing. ‘But the fact is, I made you, too. I’m sure I’m very proud of it’. ‘Made me?’ begins the judge, purple in the face. Alas, the prisoner has already waved his hand, and there are already sixty other judges, all purple in the face. Then the Prisoner, who has made all things, steps up the tribunal, his white hair flaming like a silver crown, and looks down upon the things he has made.

Let me endeavor to indicate by a kind of apologue or parallel what the trial of the Cosmos would really be. A white-haired, ragged man is convicted of having stolen a handkerchief from an old gentleman in the street, and is examined before a judge. Suppose he is convicted. And suppose after he is convicted he is able to say blandly and with unimpeachable argument, ‘It was my handkerchief’. That is the position of God or Nature, or what you will. Suppose, again, that the judge and the Court are in some doubt about this reply. The man says, still very humbly, ‘It was my handkerchief; I made it’. ‘Made it’, the judge will say, ‘what did you make it out of?’ ‘Out of nothing’, replies the prisoner, and waves his hand. Sixty handkerchiefs flutter down out of the empty air. The judge is startled, and looks keenly at the meek prisoner; nevertheless he continues: ‘You may have made the handkerchief (though in this somewhat irregular way), and so far, of course, it may be yours. All the same you seized it from this old gentleman’, The prisoner coughs slightly and looks embarrassed. ‘The fact is’, he says, ‘the fact is, I made the old gentleman, too’, ‘What did I hear you observe?’ inquires the judge, with deadly placidity, ‘made the what?’ ‘Made the old gentleman’, rejoins the prisoner. ‘I can make sixty more if you like’. He waves his hand. Instead of one old gentleman at the prosecutor’s post, looking justly indignant, there are immediately sixty old gentlemen exactly alike in a row, all looking justly indignant. The judge confers with the clerk and the foreman of the jury; the incident is one for which it is difficult for the moment to find a precedent. At length the judge says, ‘You certainly seem to have some claims over the prosecutor, having produced him out of space in a somewhat careless way, but your offence against the Court itself, your demeanour towards myself – ‘ ‘I’m really terribly sorry’, says the prisoner, blushing. ‘But the fact is, I made you, too. I’m sure I’m very proud of it’. ‘Made me?’ begins the judge, purple in the face. Alas, the prisoner has already waved his hand, and there are already sixty other judges, all purple in the face. Then the Prisoner, who has made all things, steps up the tribunal, his white hair flaming like a silver crown, and looks down upon the things he has made.

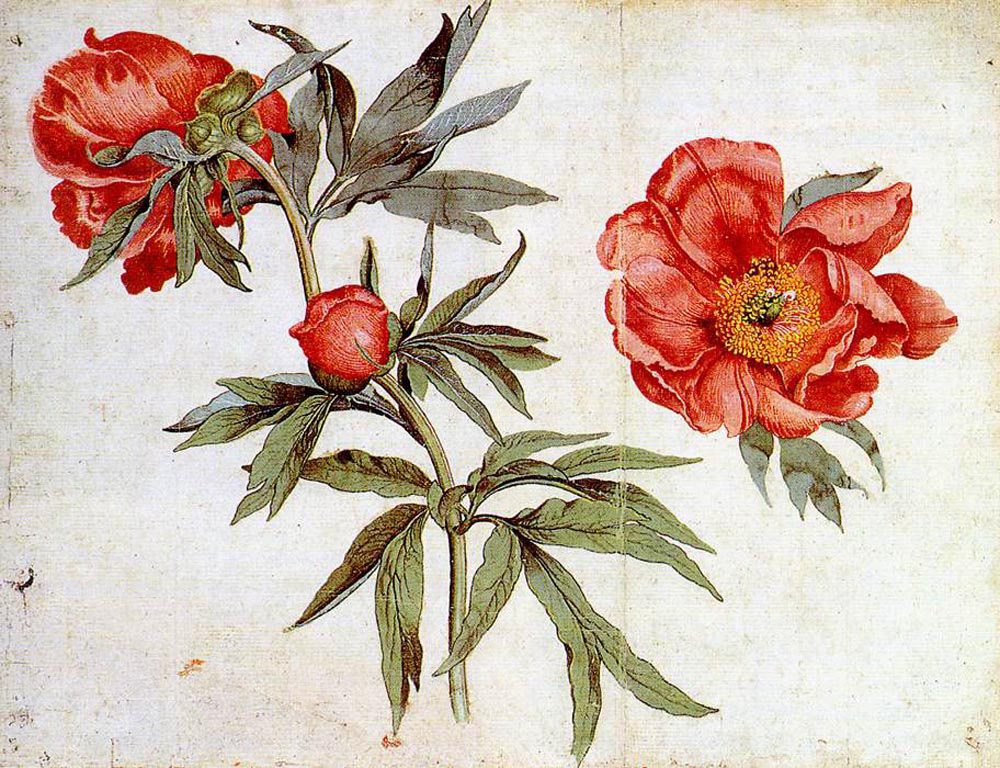

Now these things are the conditions of any protest against what Stevenson called ‘the essential decency of things’. When existence destroys the flower it is not sufficient for us to say that we admired it.

The question is not whether we admired the flower; the question is whether we could in the primal darkness of nonentity have imagined a flower, and then by the spasm of divine creation, made it. When a great man is killed in a railway accident, the question is not merely whether we would have invented the railway accident; it is also whether we could have invented the great man. The whole question in which the existence of religion is involved is whether, while we have feelings about the catastrophic, we are or are not to have feelings about the normal; that, while we curse our luck for a house on fire, we are to thank anything for a house. If we come upon a dead man, we start back in horror. Are we not to start with any generous emotion when we come upon a living man, that far greater mystery? Are we to have any gratitude for the positive miracles of life? We thank a man for passing the mustard; is there indeed nothing that we can thank for the man who passes it, for the great, fat, living, two-legged, two-eyed fairy tale, who, by the mystical avenues of ears and hands, is magically agitated to pass the mustard? Is the offering to us of that creature so small a civility, that we shall not even say a word about it? No: most men have felt that we should say a word. Most men have felt that many words even should be said in the matter. And so great cathedrals have risen in this land and little churches in every parish, and immense religions over every part of the earth, and vast theological philosophies and vast theological cosmogonies, and vast systems of heaven and earth and hell, with praises and sacrifices because men refused to regard the mustard as of more value to us than the man who passed it. If they gave thanks for one they must give thanks for the other. And so temples have been built. The man who passed the mustard ought to have a statue outside each of them.

The question is not whether we admired the flower; the question is whether we could in the primal darkness of nonentity have imagined a flower, and then by the spasm of divine creation, made it. When a great man is killed in a railway accident, the question is not merely whether we would have invented the railway accident; it is also whether we could have invented the great man. The whole question in which the existence of religion is involved is whether, while we have feelings about the catastrophic, we are or are not to have feelings about the normal; that, while we curse our luck for a house on fire, we are to thank anything for a house. If we come upon a dead man, we start back in horror. Are we not to start with any generous emotion when we come upon a living man, that far greater mystery? Are we to have any gratitude for the positive miracles of life? We thank a man for passing the mustard; is there indeed nothing that we can thank for the man who passes it, for the great, fat, living, two-legged, two-eyed fairy tale, who, by the mystical avenues of ears and hands, is magically agitated to pass the mustard? Is the offering to us of that creature so small a civility, that we shall not even say a word about it? No: most men have felt that we should say a word. Most men have felt that many words even should be said in the matter. And so great cathedrals have risen in this land and little churches in every parish, and immense religions over every part of the earth, and vast theological philosophies and vast theological cosmogonies, and vast systems of heaven and earth and hell, with praises and sacrifices because men refused to regard the mustard as of more value to us than the man who passed it. If they gave thanks for one they must give thanks for the other. And so temples have been built. The man who passed the mustard ought to have a statue outside each of them.