Warming to It

Confessions of a Former Suburbanite With a

Nonsensical Fear of Fresh Eggs

Mrs. Gina Loehr

My son came running into the house, ecstatic, and handed it to me. It was . . . warm.

I didn’t know how to react. Feelings of joy and disgust mingled inside of me in equal measure as I took hold of this edible orb, fresh from our new little coop. Our first egg had just been laid! Could food get any fresher? The children’s chicken project had come to fruition, and the hens were finally productive. What joy!

Yet, that round, white object in my hand felt unlike any egg I had ever held. It didn’t come out cold and clean from a refrigerated carton. It came straight from the underside of a bird. A warm and dusty bird. Who sat on it. And now here it sat in my hand, still warm and dusty. It sat, and it silently asked to be consumed like any other egg of my suburban history. I wasn’t sure I could stomach the thought (much less the egg).

Years earlier, an earthy friend with a flock chickens in her barn (and a flock of children in her house), had sent me home with a dozen of their brown eggs. I had cracked one open and seen something reddish floating in the goo. I instantly trashed the specimen along with its eleven compatriots. Danger — dispose — sanitize! Tie up the trash bag tight and take it outside immediately. Had someone offered me a hazmat suit, I might have considered it. I resolved on the spot that I would never risk farm-fresh eggs again.

Years earlier, an earthy friend with a flock chickens in her barn (and a flock of children in her house), had sent me home with a dozen of their brown eggs. I had cracked one open and seen something reddish floating in the goo. I instantly trashed the specimen along with its eleven compatriots. Danger — dispose — sanitize! Tie up the trash bag tight and take it outside immediately. Had someone offered me a hazmat suit, I might have considered it. I resolved on the spot that I would never risk farm-fresh eggs again.

But here, a decade later, I had six chickens in our barn (and just as many children in my house). I now found myself in possession of another farm-fresh egg, a warm one this time, and now too with the moral duties of my role as supportive mother weighing on my shoulders. Gagging while my son stood there glowing was simply not an option. He was so anxious to enjoy this first harvest. And I had approved the whole endeavor. He and his sisters saved their allowance, built the coop, bought the birds, and tended them for five months in hungry anticipation of this very moment.

So I decided . . . to make a cake.

Despite a solid decade of farm life, some growth in my own earthiness, and any number of incremental triumphs over squeamishness, I was apparently not yet ready to crack fully out of my shell. Serving the thing sunny-side-up was just too risky. Hidden in a cake, perhaps, the egg could be appreciated without too much fear. I don’t remember how the cake turned out, but I remember feeling relieved when twenty-four hours passed and no one got sick.

Hidden in a cake, perhaps, the egg could be appreciated without too much fear. I don't remember how the cake turned out, but I remember feeling relieved when twenty-four hours passed and no one got sick.

How strange and irrational our internal reactions can sometimes be. My neural pathways regarding such matters were forged as a child, mapped to the topography of the dairy aisle at Kroger’s. Intellectually I knew, of course, that eggs came from chickens — I’d probably decorated the event on farm-themed coloring sheets in kindergarten. But psychologically, eggs came from styrofoam containers, twelve at a time, stacked behind glass doors in well-lit, refrigerated corridors. Eggs were not supposed to be warm. Which is odd, because I’ve never consumed one without cooking it first.

I recall a similarly strange reaction when I realized that milk straight from a cow comes out warm. Warm milk from the microwave, which has previously spent a week being cold milk in the refrigerator, seemed different than warm milk that is three minutes old. Why should I be unsettled and confused by the warmth of an animal, a living creature like myself, while being comforted by the warmth of a machine?

Surely, it makes no sense. But so much of life is just a matter of what we’re used to. This orientation toward mechanization sterilizes and chills not just our food but our relationship to our food. It obscures the true warmth of an affection that ought to exist between us and the creatures that feed us, the creatures we are called to tenderly care for while on this earth. Besides which, it’s not at all obvious why hyper-local production would increase any actual risks, as I now ponder every time I hear about a recall from some far-off facility over whose operations I have no control whatsoever.

Surely, it makes no sense. But so much of life is just a matter of what we’re used to. This orientation toward mechanization sterilizes and chills not just our food but our relationship to our food. It obscures the true warmth of an affection that ought to exist between us and the creatures that feed us, the creatures we are called to tenderly care for while on this earth. Besides which, it’s not at all obvious why hyper-local production would increase any actual risks, as I now ponder every time I hear about a recall from some far-off facility over whose operations I have no control whatsoever.

It obscures the true warmth of an affection that ought to exist between us and the creatures that feed us, the creatures we are called to tenderly care for while on this earth.

In any case, I thank God for neural plasticity later in life. I was able to get past my hangups, and all of those discordant feelings (well, most of them) worked their way out of my system after a while. Through daily growth and exposure, my emotional reactions have started to align with my intellectual understandings, and both of them have improved.

These days, I fry up dozens of farm eggs every week for our school-day family breakfasts. Some of them come in dirty and have to be washed. Some have red stuff in the goo. And when the kids are on top of the chore schedule, the eggs often come in the house still warm. But I don’t mind it anymore. In fact, it feels kind of cozy.

These days, I fry up dozens of farm eggs every week for our school-day family breakfasts. Some of them come in dirty and have to be washed. Some have red stuff in the goo. And when the kids are on top of the chore schedule, the eggs often come in the house still warm. But I don’t mind it anymore. In fact, it feels kind of cozy.

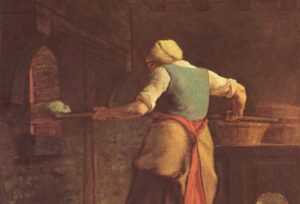

So, when I’m standing at the stove scrambling those morning eggs, considering the years of self-sufficiency, the years of growth for my children as they care for creation and practice diligence, the years of my becoming less squeamish and more hearty, I’m grateful and content. What’s more, these birds have kept my family in breakfast while the chickenless among us, dependent upon supermarkets for their omelets, have been subject to ongoing egg shortages and price increases.

We had a spell recently where the birds stopped laying. Molting or weather or disease or the feed — we didn’t know — had put us back at the mercy of the market. We bought cold, clean, overpriced eggs for a time. Then, just when the word “butchering” had crept into some conversations, my son burst through the kitchen door, with a warm egg held high in his hand and shouted for all to hear, “We’ve got an egg!” This time, I only felt joy.