—Ink and Echoes—

On the Perks and Pitfalls of Paper Money

From the Floor of the United States Senate

Daniel Webster

—1834—

Is it possible,—is it possible that twelve millions of intelligent people can be expected voluntarily to subject themselves to severe distress, of unknown duration, for the purpose of making trial of an experiment like this? Will a nation that is intelligent, well informed of its own interest, enlightened, and capable of self-government, submit to suffer embarrassment in all its pursuits, loss of capital, loss of employment, and a sudden and dead stop in its onward movement in the path of prosperity and wealth, until it shall be ascertained whether this new-hatched theory shall answer the hopes of those who have devised it? Is the country to be persuaded to bear every thing, and bear patiently, until the operation of such an experiment, adopted for such an avowed object, and adopted, too, without the co-operation or consent of Congress, and by the executive power alone, shall exhibit its results?

In the name of the hundreds of thousands of our suffering fellow-citizens, I ask, for what reasonable end is this experiment to be tried? What great and good object, worth so much cost, is it to accomplish? What enormous evil is to be remedied by all this inconvenience and all this suffering? What great calamity is to be averted? Have the people thronged our doors, and loaded our tables with petitions for relief against the pressure of some political mischief, some notorious misrule, which this experiment is to redress? Has it been resorted to in an hour of misfortune, calamity, or peril, to save the state? Is it a measure of remedy, yielded to the importunate cries of an agitated and distressed nation? Far, Sir, very far from all this. There was no calamity, there was no suffering, there was no peril, when these measures began. At the moment when this experiment was entered upon, these twelve millions of people were prosperous and happy, not only beyond the example of all others, but even beyond their own example in times past.

In the name of the hundreds of thousands of our suffering fellow-citizens, I ask, for what reasonable end is this experiment to be tried? What great and good object, worth so much cost, is it to accomplish? What enormous evil is to be remedied by all this inconvenience and all this suffering? What great calamity is to be averted? Have the people thronged our doors, and loaded our tables with petitions for relief against the pressure of some political mischief, some notorious misrule, which this experiment is to redress? Has it been resorted to in an hour of misfortune, calamity, or peril, to save the state? Is it a measure of remedy, yielded to the importunate cries of an agitated and distressed nation? Far, Sir, very far from all this. There was no calamity, there was no suffering, there was no peril, when these measures began. At the moment when this experiment was entered upon, these twelve millions of people were prosperous and happy, not only beyond the example of all others, but even beyond their own example in times past.

There was no pressure of public or private distress throughout the whole land. All business was prosperous, all industry was rewarded, and cheerfulness and content universally prevailed. Yet, in the midst of all this enjoyment, with so much to heighten and so little to mar it, this experiment comes upon us, to harass and oppress us at present, and to affright us for the future.

[I]n the midst of all this enjoyment, with so much to heighten and so little to mar it, this experiment comes upon us, to harass and oppress us at present, and to affright us for the future.

Sir, it is incredible; the world abroad will not believe it; it is difficult even for us to credit, who see it with our own eyes, that the country, at such a moment, should put itself upon an experiment fraught with such immediate and overwhelming evils, and threatening the property and the employments of the people, and all their social and political blessings, with severe and long-enduring future inflictions.

And this experiment, with all its cost, is to be tried, for what? Why, simply, Sir, to enable us to try another “experiment”; and that other experiment is, to see whether an exclusive specie currency may not be better than a currency partly specie and partly bank paper. . . .

I know, indeed, that all paper ought to circulate on a specie basis; that all bank-notes, to be safe, must be convertible into gold and silver at the will of the holder; and I admit, too, that the issuing of very small notes by many of the State banks has too much reduced the amount of specie actually circulating. It may be remembered that I called the attention of Congress to this subject in 1832, and that the bill which then passed both houses for renewing the bank charter contained a provision designed to produce some restraint on the circulation of very small notes. I admit there are conveniences in making small payments in specie; and I have always, not only admitted, but contended, that, if all issues of bank-notes under five dollars were discontinued, much more specie would be retained in the country, and in the circulation; and that great security would result from this.

But we are now debating about an exclusive specie currency; and I deny that an exclusive specie currency is the best currency for any highly commercial country; and I deny, especially, that such a currency would be best suited to the condition and circumstances of the United States. . . . I have supposed that it was admitted that there are particular and extraordinary advantages in a safe and well regulated paper currency; because in such a country well regulated bank paper not only supplies a convenient medium of payments and of exchange, but also, by the expansion of that medium in a reasonable and safe degree, the amount of circulation is kept more nearly commensurate with the constantly increasing amount of property; and an extended capital, in the shape of credit, comes to the aid of the enterprising and the industrious. . . . This is so plain, that no man of reflection can doubt it.

But we are now debating about an exclusive specie currency; and I deny that an exclusive specie currency is the best currency for any highly commercial country; and I deny, especially, that such a currency would be best suited to the condition and circumstances of the United States. . . . I have supposed that it was admitted that there are particular and extraordinary advantages in a safe and well regulated paper currency; because in such a country well regulated bank paper not only supplies a convenient medium of payments and of exchange, but also, by the expansion of that medium in a reasonable and safe degree, the amount of circulation is kept more nearly commensurate with the constantly increasing amount of property; and an extended capital, in the shape of credit, comes to the aid of the enterprising and the industrious. . . . This is so plain, that no man of reflection can doubt it.

I know not, therefore, in what words to express my astonishment, when I hear it said that the present measures of government are intended for the good of the many instead of the few, for the benefit of the poor, and against the rich; and when I hear it proposed, at the same moment, to do away with the whole system of credit, and place all trade and commerce, therefore, in the hands of those who have adequate capital to carry them on without the use of any credit at all. This, Sir, would be dividing society, by a precise, distinct, and well-defined line, into two classes; first, the small class, who have competent capital for trade, when credit is out of the question; and, secondly, the vastly numerous class of those whose living must become, in such a state of things, a mere manual occupation, without the use of capital or of any substitute for it.

Now, Sir, it is the effect of a well-regulated system of paper credit to break in upon this line thus dividing the many from the few, and to enable more or less of the more numerous class to pass over it, and to participate in the profits of capital by means of a safe and convenient substitute for capital; and thus to diffuse far more widely the general earnings, and therefore the general prosperity and happiness, of society. . . .

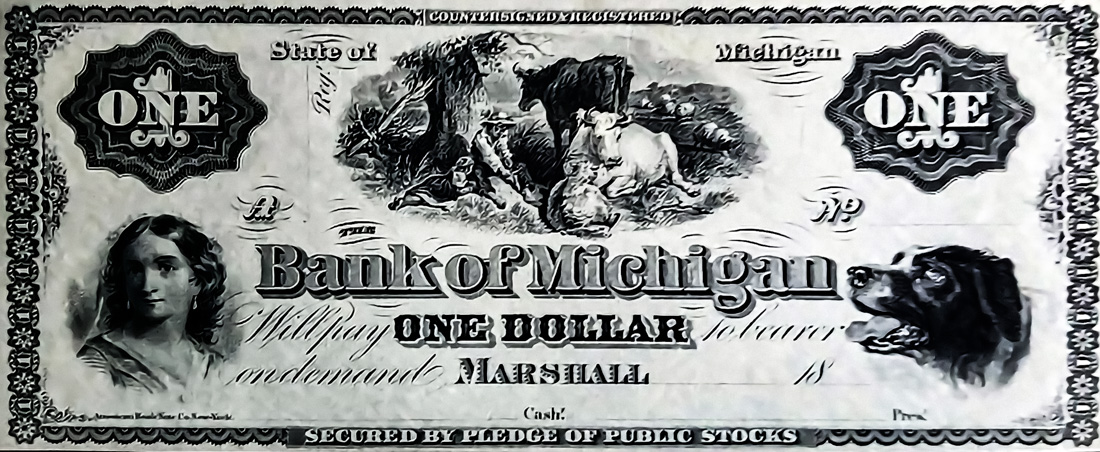

Our system has hitherto been one in which paper has been circulating on the strength of a specie basis; that is to say, when every bank-note was convertible into specie at the will of the holder. This has been our guard against excess. While banks are bound to redeem their bills by paying gold and silver on demand, and are at all times able to do this, the currency is safe and convenient. Such a currency is not paper money, in its odious sense. It is not like the Continental paper of Revolutionary times; it is not like the worthless bills of banks which have suspended specie payments. On the contrary, it is the representative of gold and silver, and convertible into gold and silver on demand, and therefore answers the purposes of gold and silver; and so long as its credit is in this way sustained, it is the cheapest, the best, and the most convenient circulating medium. I have already endeavored to warn the country against irredeemable paper; against the paper of banks which do not pay specie for their own notes; against that miserable, abominable, and fraudulent policy, which attempts to give value to any paper, of any bank, one single moment longer than such paper is redeemable on demand in gold and silver.

I have already endeavored to warn the country against irredeemable paper . . . against that miserable, abominable, and fraudulent policy, which attempts to give value to any paper, of any bank, one single moment longer than such paper is redeemable on demand in gold and silver.

I wish most solemnly and earnestly to repeat that warning. I see danger of that state of things ahead. I see imminent danger that a portion of the State banks will stop specie payments. The late measure of the Secretary, and the infatuation with which it seems to be supported, tend directly and strongly to that result. Under pretense, then, of a design to return to a currency which shall be all specie, we are likely to have a currency in which there shall be no specie at all. We are in danger of being overwhelmed with irredeemable paper, mere paper, representing not gold nor silver; no, Sir, representing nothing but broken promises, bad faith, bankrupt corporations, cheated creditors, and a ruined people. . . .

We require neither irredeemable paper, nor yet exclusively hard money. We require a mixed system. We require specie, and we require, too, good bank paper, founded on specie, representing specie, and convertible into specie on demand. We require, in short, just such a currency as we have long enjoyed, and the advantages of which we seem now, with unaccountable rashness, about to throw away.