Why Jo Has To Marry Professor Bhaer

A Review of Little Women , Then and Now

Mrs. Rebekah Wojtysiak

There are many things that could be said (and some of them have been said) about the various film adaptations of Little Women. It seems each generation must have a new film to praise — or bemoan, as the case may be. One such adaptation, a film likely to be familiar to lady readers and endured by the gentlemen who love them, is the 2019 feature film directed by Greta Gerwig. This version takes many liberties with the novel’s story, characters, and even clothing (Amy wearing Uggs in 1863, anyone?), but one of the most egregious departures from the original text is the film’s treatment of Jo’s happy ending with her friend and eventual love interest, Professor Fritz Bhaer.

According to the film, Jo adds a Hollywood-esque happy ending for her fictional self in order to sell her novel — depicted with somewhat bizarre flashes back and forth along the timeline and then a jump ahead to a Jo-Louisa May Alcott hybrid attempting to sell Little Women to the editor of a newspaper called The Daily Volcano. This modern rom-com trope has Jo prettying herself up and racing off in Amy’s carriage (with Meg and Amy also present for moral support) to catch the Professor before he boards a train that will take him away from Jo forever. According to various critics and opinionated persons, the film ends either ambiguously (does the Professor-chasing really happen?) or decidedly, with Jo as a happy, successful, childless businesswoman who owns a school at which she employs her family members.

Regardless of the view one takes on the definiteness or ambiguity of the film’s ending, such an ending fundamentally alters the purpose and power of the original novel, drastically reducing the story’s potential to affect the reader or viewer in a positive and even grace-filled manner — especially for a young lady who reads or views Little Women during the crucial period of adolescence, or, later, a single woman whose life has been impacted by tragedy. It is a step too far. In short: yes, Jo does have to get married, but not for the reasons the film depicts.

Regardless of the view one takes on the definiteness or ambiguity of the film’s ending, such an ending fundamentally alters the purpose and power of the original novel, drastically reducing the story’s potential to affect the reader or viewer in a positive and even grace-filled manner — especially for a young lady who reads or views Little Women during the crucial period of adolescence, or, later, a single woman whose life has been impacted by tragedy. It is a step too far. In short: yes, Jo does have to get married, but not for the reasons the film depicts.

Little Women, Louisa May Alcott’s nineteenth-century novel about the four March sisters, seems to possess a special magic for girls of a certain age. Most ladies read the novel for the first time when they are between the ages of eleven and fourteen, and it leaves a lasting impression. The trials, travails, and joys of girlhood and young womanhood are there expressed in a very intimate way; from the first line, “It won’t be Christmas without any presents!”, the reader is drawn into the lives of the March family almost as though she herself were part of the clan. Meg, Jo, Beth, and Amy grow up before the reader’s eyes, and what stony-hearted girl will say that she neither laughed nor cried while reading the novel?

Meg, Jo, Beth, and Amy grow up before the reader’s eyes, and what stony-hearted girl will say that she neither laughed nor cried while reading the novel?

Although it seems merely picturesque at first, the story of the March sisters unabashedly addresses timeless and important truths and experiences in the lives of young ladies — or “little women” as Mr. March calls his daughters. From peer pressure, pride, and bad temper, to birth, marriage, and death, few stones are left unturned. One particular stone worth turning concerns how the novel — and the 2019 adaptation — deals with death and grief.

Partway through the novel, Beth contracts scarlet fever while visiting a poor family nearby. Although she comes close to death, Beth nevertheless survives her illness. While the disease does not take Beth’s life, it seems to take her strength, and even after her convalescence, she remains frail and weak. Her older, headstrong sister Josephine (commonly called Jo) takes it upon herself to care for Beth, sparing nothing in the hope that her sister will again grow strong.

Despite the efforts lovingly lavished on her, Beth’s health eventually deteriorates, and she passes away. The depiction of her death, though, is infused with a sense of hope; although the process of dying is clearly painful, both for Beth and for her family as they care for her, it is not without a certain sense of peace. Here, in fact, is a very intimate glimpse into the traditional Christian worldview: although Beth’s family mourns her, they realize that death is not the enemy. Rather, they look upon her leaving this world as a sort of home-going, a carefully prepared-for journey understood as a flight from her loving temporal family to the best of Fathers in eternity. That is, while Beth’s passing definitely causes pain to those who love her, they receive great consolation from their hope in the promise of Heaven and in Beth’s peaceful repose with Christ, like those gone before her in faith. This hope, however, is a precious gift that is sadly lost in our modern society, a loss that is apparent in the 2019 film version of Little Women.

Firstly, as stated by the film’s Daily Volcano editor, an assumption is made that the original novel requires marriage or death of all of its heroines merely for reasons of social propriety: the novel’s heroine is expected to be dead or married by the end of the book because that’s what people expect to read, and because polite society considers it unthinkable for an unmarried woman to be successful and happy. This is because members of society at large are all under the thumb of repressive social mores. In short, had Alcott not been brainwashed by the Victorian worldview, she would have done things this way.

On the contrary, this interpretation exposes the filmmakers’ deep misunderstanding of Alcott and her novel. The real Louisa May Alcott was no prim China aster, raised on governesses and high-buttoned collars. In fact, her parents were heavily involved in the Transcendentalist movement, with her father frequently beginning new idealistic ventures that rarely, if ever, bore fruit. Among these were an integrated school for boys and girls that was forced to close when it began to welcome children of color, and a short-lived vegetarian commune where a young Louisa and her sisters were encouraged to wear short tunics and pants, rather than the customary dresses. As a result, when the famous author was yet a young girl, her family often faced grinding poverty as well as gossip; far from being well-respected, Alcott herself was accustomed to being considered odd. It is unlikely that Alcott was overly worried about appearing strange to her neighbors or to American society at large. Could societal expectations have had some influence on her decision to give Jo a rather conventional ending? Certainly; conventional endings do sell, and authors understandably want to make money and feed their families. Thus, Alcott’s choice of happily-ever-after may, upon its writing, have been nothing more than a smart business decision. In this case, however, what sells books also communicates a deeper truth.

On the contrary, this interpretation exposes the filmmakers’ deep misunderstanding of Alcott and her novel. The real Louisa May Alcott was no prim China aster, raised on governesses and high-buttoned collars. In fact, her parents were heavily involved in the Transcendentalist movement, with her father frequently beginning new idealistic ventures that rarely, if ever, bore fruit. Among these were an integrated school for boys and girls that was forced to close when it began to welcome children of color, and a short-lived vegetarian commune where a young Louisa and her sisters were encouraged to wear short tunics and pants, rather than the customary dresses. As a result, when the famous author was yet a young girl, her family often faced grinding poverty as well as gossip; far from being well-respected, Alcott herself was accustomed to being considered odd. It is unlikely that Alcott was overly worried about appearing strange to her neighbors or to American society at large. Could societal expectations have had some influence on her decision to give Jo a rather conventional ending? Certainly; conventional endings do sell, and authors understandably want to make money and feed their families. Thus, Alcott’s choice of happily-ever-after may, upon its writing, have been nothing more than a smart business decision. In this case, however, what sells books also communicates a deeper truth.

Far from being repressed or stuck in a conventional box, Jo, like the author who created her, continually asserts her independence: she rejects a terrible marriage proposal, lives on her own in New York, and even finds some limited success as a writer. Jo’s friendship with Professor Bhaer during this time in New York also brings her great joy and, in short, we may perhaps consider Josephine March a “liberated woman.” This independence, however, does not make her happy, and she longs for her family and her home. When Beth’s illness and eventual death strikes, Jo puts all of her fierce determination into providing for her sister and her family: Jo becomes Beth’s primary caregiver and, after Beth’s passing, Jo takes over her sister’s former place in the house, doing much hard domestic work. Beth’s death is, of course, devastating to Jo. The excruciating pain of losing her sister forces a change in Jo: her grief colors everything in her world, at least temporarily. This is to be expected; it would be a cruel and bizarre person who remained completely unaffected at the death of a beloved sister, especially one on whom she had lavished so much love and care. The threat for Jo, however, is that she will abandon her hopes for future joy. That is, there exists a danger of Jo allowing her grief to have too strong a pull over her, closing her off to divine grace. Again, Jo’s resilience here shines through, as our heroine does not remain paralyzed.

Even before Beth dies, Jo takes the first step towards healing when she writes the poem “My Beth”, and uses the talents God has given her to channel her pain into something beautiful. After the funeral, Jo’s healing continues in her close relationships with both her parents; in sharing their sorrow, all three find hope and consolation. Finally, when Jo allows the memories, both happy and painful, to wash over her in her writing of the novel about the March girls’ childhood, she faces her grief head-on with the hope of eternal life. Beth is not gone forever; she is merely gone on before the rest of her family. Sending such a precious story out into the world to be published, read, and critiqued exemplifies the fact that grief no longer holds sway over Jo, and that hope now helps to sustain her. Professor Bhaer, though at a great geographic distance, recognizes this action of grace when Jo’s writings again begin to be published.

Finally, when Jo allows the memories, both happy and painful, to wash over her in her writing of the novel about the March girls’ childhood, she faces her grief head-on with the hope of eternal life.

Such hope is a grace that is never left incomplete. Thus, some time after Beth’s passing, when Professor Bhaer re-enters Jo’s life and seeks–in his own sweet, shy way–to court and propose marriage to her, the last piece of what J.R.R. Tolkien might call Jo’s eucatastrophe falls into place. The concept of eucatastrophe, or a divinely-orchestrated happy turning of the tide at the pinnacle of tragedy, is necessarily modeled on Christ’s death and Resurrection, and is fundamentally necessary to the hopeful worldview of every committed Christian: if we do not keep this happy ending in mind, we easily miss the great gifts God wishes to give us. For Jo, to reject the Professor’s suit would be to reject what becomes a benediction of grace not only for her, but for her future children and students.

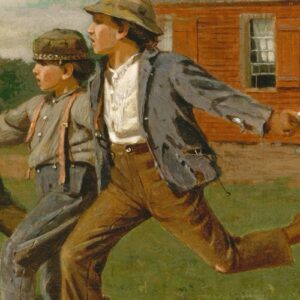

The reader sees that future in the sequel to Little Women, entitled Jo’s Boys, when Jo and her husband run a boarding school called Plumfield. Here, Jo becomes not only a teacher but also a surrogate mother for the young boys, many of whom have difficult backgrounds or troubled pasts. Such a great role requires deep strength, and can best be filled by a woman like Jo, a former tomboy who has known tragedy and sorrow.

At the time of the Professor’s proposal in Little Women, however, none of this is known. This eucatastrophe is only hinted at, and there seems to be a temptation for Jo to reject Professor Bhaer’s gentle proposal: that is, she may be inclined to distrust what seems too good to be true. At this point in the novel, the reader, especially a young woman affected by tragedy in her own life, can look upon Jo March as a kindred spirit; one can easily identify with her struggles, and look to her as a kind of literary friend. Thus, the way Jo’s story turns out can have a significant effect on the reader, regardless of the reader’s own circumstances. For many young women, Jo is a universal heroine.

In writing such a sympathetic, realistic character as Jo March, Alcott here gives a beautiful map of the human heart–or at least a segment of it–beginning to arise from grief. There is a human tendency, as the black clouds lift and sunlight begins to return, to seek a kind of equilibrium; as long as nothing too bad happens, I am satisfied, one may think. I will not ask for too much. I shall not rock the boat. But accepting this view can, in fact, lead one into a kind of sin against hope, for God is not a god of inches and if-thens; he does not make that kind of deal. Rather, he is our Father who desires nothing more than our happiness with him forever, where all tears will be wiped away. To paraphrase a line from another film, Shadowlands, the pain now will be part of the happiness then. Where better can this be seen than in the Cross and Resurrection of Christ? God, then, desires to give us joy far beyond anything we can imagine, beginning even in this life as a limited foretaste of the next.

Jo therefore uses what has been a fault–her strong will–to overcome this temptation to play it safe: in consenting to marry her beloved Professor Bhaer, Jo chooses the unknown over the known, the mysterious new beginning over the safe box of a life of spinsterhood. She chooses to let herself become vulnerable again, risking a broken heart for the sake of the man she loves. Indeed, Alcott seems to convey, it is love, and love rooted in Divine Charity, that alone can give us the courage to make such a choice. As we discover in Little Men, the second of Alcott’s books, life is not easy for the “Mrs. Jo” she becomes, but it is full to bursting with joy and love.

Jo therefore uses what has been a fault–her strong will–to overcome this temptation to play it safe: in consenting to marry her beloved Professor Bhaer, Jo chooses the unknown over the known, the mysterious new beginning over the safe box of a life of spinsterhood. She chooses to let herself become vulnerable again, risking a broken heart for the sake of the man she loves. Indeed, Alcott seems to convey, it is love, and love rooted in Divine Charity, that alone can give us the courage to make such a choice. As we discover in Little Men, the second of Alcott’s books, life is not easy for the “Mrs. Jo” she becomes, but it is full to bursting with joy and love.

Conversely, in altering Jo’s storyline and removing the satisfaction of a simple, joyful life of sacrifice, the 2019 film offers a poor substitute. In this case, mere material success and life as a single person do not force Jo to grow, nor to make use of her struggles to help others; in short, it is not a happy life, but a selfish one. Far from the excitement promised by the glamorous shots of Plumfield school and novel printings as depicted in the film, such a closed-in life can actually be quite boring. When one rejects discomfort and vulnerability, when life is ordered to one’s own convenience, the thrill of adventure is lost. If one is not open to the messiness — even pain — of one’s vocation, whether to family life, religious life, or life as a single person, one cannot also be open to priceless riches and joys. In Jo’s case, rejecting her dear Fritz and focusing her energies on writing and business ventures rob her of a full, beautiful life. Further, for the viewer, a great consolation is lost. The tender joy belonging to the future, such as in a loving, happy marriage, often seems unthinkable during active grief; Jo’s story, while fictional, communicates an important truth, and can be a great help to the reader in healing from tragedy. Far from being an empowering statement, the film’s rejection of Jo’s conventional ending actually places our heroine in a lonely, boring box.

Whether Alcott was aware of the powerful message conveyed by the finalé of her novel, or was simply being a smart businesswoman is immaterial: Jo’s happy ending in marriage and children gives proof to the reader that the sun will shine again, that joy will return after loss. Thus, by altering the storyline to remove the certainty of Jo’s marriage, the 2019 film removes a powerful and lifelike testimony to life after active grief. It instead substitutes material success and independence as cheap consolation prizes. It would be foolish to debate whether women can be fulfilled and happy while single or in religious life — of course they can be so. In this case, however, Little Women‘s Jo finds her purpose in the self-giving love of marriage, children, and teaching; her long toil bears much fruit. That fundamental truth cannot be excised from a work so important in the lives of young women without a great and tragic loss. Perhaps this truth is one that the filmmakers in question have yet to learn