The Shovel & the Mountain

Mrs. Gina Loehr

I was thirty-one years old when I learned how to use a shovel. It’s true. I had moved some snow around on my parents’ driveway when I was young. I had dug a few holes in garden plots to plant some vegetables along the way. But I had never really worked with a shovel. Anything I did was more for amusement than for true productivity. I surely never broke a sweat with a shovel in my hand. Until the day the mulch arrived.

I had been married for a while and had moved from suburbia to the Loehr family farm. And, more recently, I had naïvely agreed to my mother-in-law’s suggestion that we tidy up the yard around the ancient farmhouse, which my husband had remodeled upon our nuptials. Not long after I gave my unwitting thumbs-up on this plan, some truck or another showed up, backed onto the concrete pad by the calf hutches, dumped a veritable mountain of wood chips on it, and drove away. “Hey — come back here! You accidentally dumped a veritable mountain of . . . .”

No, there had been no accident. Unbeknownst to me, my mother-in-law, Rosie, had ordered what I later learned was “a few yards” of mulch, to be delivered to the farm.

I hadn’t any idea what was going to be done with such a vast amount of mulch. Images of the little plastic bags of wood chips from the hardware store, which fit comfortably in the trunk of a small sedan, came floating through my mind. Was this unpackaged Everest, this precipice of potential landscaping, actually the same product? How was it going to get itself around our trees and our flower beds? I found myself genuinely befuddled.

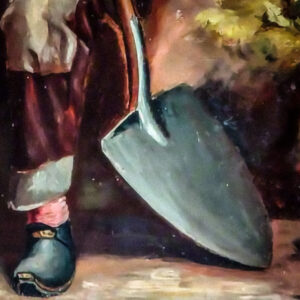

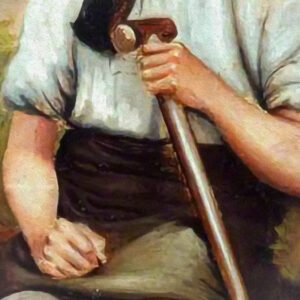

Soon enough, Rosie came down from next door pushing a wheelbarrow with two shovels in it. These devices were unlike any shovels I had ever met. Here was not the red plastic-handled “snow shovel” of my youth. Nor the shiny, memory-foam-grip garden spade of young adulthood. No. These were farm tools. Imagine slightly rusted steel handles fitted atop thick, cumbrous, wooden shafts that were . . . well, they were basically logs. Each log ended in a colossal piece of steel, straight-tipped and concave. Rosie wheeled over to the mountain and casually grabbed one of the shovels.

Soon enough, Rosie came down from next door pushing a wheelbarrow with two shovels in it. These devices were unlike any shovels I had ever met. Here was not the red plastic-handled “snow shovel” of my youth. Nor the shiny, memory-foam-grip garden spade of young adulthood. No. These were farm tools. Imagine slightly rusted steel handles fitted atop thick, cumbrous, wooden shafts that were . . . well, they were basically logs. Each log ended in a colossal piece of steel, straight-tipped and concave. Rosie wheeled over to the mountain and casually grabbed one of the shovels.

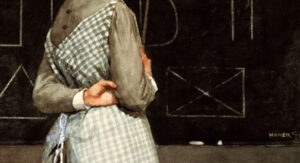

She’s a quiet type. I wasn’t given instructions. But I surmised that I was to pick up the other one. I reached for it, girding my strength by calling to mind the title I had won on my wedding day, Farmer’s Wife. But the thing was so dang heavy. One hand on the handle wasn’t going to get this machine out of the barrow. I placed my other hand in the middle of the ponderous shaft and successfully hoisted it high enough to clear the edge of the barrow. A shovel removed from a wheelbarrow. Success!

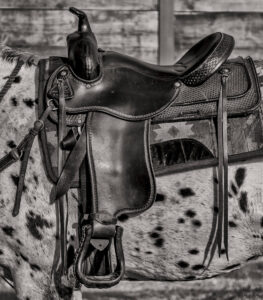

I reached for it, girding my strength by calling to mind the title I had won on my wedding day, Farmer’s Wife.

Then Rosie started moving mulch from the mountain to the wheelbarrow. With only that shovel and her arms. One heap at a time. It slowly dawned on me that we were going to get this mulch around the trees and the flower beds. Us. Me, my mother-in-law, and two preposterously large shovels.

I tried hard to summon faith the size a mustard seed. I took a deep breath. “Farmer’s Wife,” I told myself. “I think I can; I think I can . . . .” And I thrust my assigned shovel into the guts of Everest.

Baby landslides of the uppermost chips dribbled into my steel dish as it hit the mountain wall. Dribble. Dribble. I kept at it. But my collection always seemed minuscule compared to Rosie’s, despite the fact that my stabs were so vigorously well-intentioned. Deep down I was a little relieved. It was hard enough just moving the shovel itself from pile to wheelbarrow; I didn’t need lots of stuff on it as well.

But soon, it became embarrassingly apparent that my seventy-year-old companion was doing the lion’s share of the work. And I was the one panting and sweating, even as I made my meager contributions to the pot.

Finally, a few loads in, Rosie had mercy on my ignorance.

“Put your shovel down here,” she suggested in her gentle way, indicating that the straight tip of the tool, if laid flush with the concrete at ground level, could slide in under the pile and be pulled back out heaping full of mulch, all with relatively little effort. I adopted the strategy. In no time I became a legitimate part of the team; tricks of the trade do make a difference. And, remarkably (to me at least), we did it. It was hard work, and it took a long time, but we leveled that mountain and landscaped the yard.

It was hard work, and it took a long time, but we leveled that mountain and landscaped the yard.

This was, perhaps, the moment when I first realized that my life had been one almost entirely devoid of manual labor. I did household chores, mowed my grandma’s lawn once, and pulled some occasional weeds. I broke a number of sticks each autumn and stacked them neatly in piles. I think I may have helped paint a wall or two. But I had never stood in front of a massive physical task and attacked it, boldly, unflinching, with nothing but my bodily strength, a good solid tool, and quiet confidence in the power of the human will.

I have since had many more occasions to do manual labor and to reflect on my lack of history with it. And my conclusion is that, in spite of a lifetime of material comforts, I have experienced a real form of poverty.

I have since had many more occasions to do manual labor and to reflect on my lack of history with it. And my conclusion is that, in spite of a lifetime of material comforts, I have experienced a real form of poverty.

Without disregarding the trials of actual economic impoverishment, I mean to say that a life without manual labor, the need for it, the expectation of it, the training in it, is a life that lacks a kind of richness. It is true that a person can also be impoverished through lack of education, lack of literacy in language or music or art or poetry, but ever since that day when I got some literacy in shoveling, that day when Rosie gave me the gift of her experience and the witness of her resilience, I have wished that there had been greater thrusts of manual work throughout my formative years. I can articulate what I see I lack, but I’m convinced it would have been far more valuable to have it than to have the ability to talk, write, and think about it.

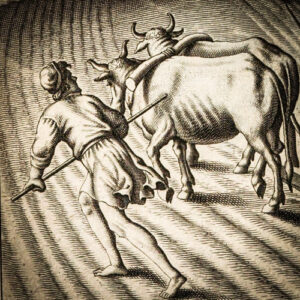

By the merciful grace of God — a God who chose to be incarnate and labor for a while as a carpenter, hefting about great, heavy logs of wood all day — I have the opportunity now to raise children who will not be devoid of the wealth earned by hard work. I daily encourage their efforts and try to remain humble as my offspring perform feats of strength that I can hardly muster: wrangling disgruntled pigs, carrying enormous pails of heifer feed across the pasture, enduring heat and dust and deerflies as they trudge through fields picking stones for hours at a time. And, not infrequently, shoveling.

The greatest fruit of this kind of wealth is not actually accomplishing the job itself. It is having that ready store of diligence, perseverance, muscle, and hope. It is having the patience and the pluck needed to square off against a grand challenge and find a way to get through it . . . or over it, or under it, or around it, or, as the case may be, to pick it up one scoop at a time and move it somewhere else.

We’ll all face our share of hardships in life. There’s no avoiding it. But these mountains are not so intimidating, not so frightening, not such daunting obstacles for those who have learned how to use a shovel.