Massaged by the Media

Staying Afloat in an Environmental,

Media Maelstrom

Dr. Jeff Gardner

In the 1970s, Bob Hunter was the driving force behind the environmental activist group Greenpeace. Brazenly committed to raising Greenpeace’s public profile, he was a self-described media insurgent, openly rejecting objectivity and embracing sensationalism to inject alarmist hype into the environmental movement at an intensity that put Rachel Carson to shame. Hunter was also a devotee of Marshall McLuhan, who was, some say, the most influential media thinker and scholar of the twentieth century. McLuhan argued that electronic media, such as television, could take control of our senses like no other media and could “work us over completely.”

Hunter took McLuhan’s theories as gospel and developed a media tactic he called “mind bombs”: Staged or arranged video or still images so shocking that they would burn themselves into the viewers’ minds and memories. Hunter would, for example, charter a broken-down sailboat into a nuclear test zone or place himself between whales and the canon-fired harpoons used to kill them, all intending to shock the viewer into taking action.

While there is much to admire about Greenpeace’s opposition to testing nuclear weapons and industrial-scale animal harvesting, there is a not-so-subtle irony about Hunter’s implementation of McLuhan’s media theories. McLuhan understood that electronic media had the power to hijack our thoughts and reshape how we see ourselves and the world around us. McLuhan also understood and was deeply troubled by corporate media’s aim to reduce a person’s worth to how much he or she could be persuaded to consume. Mass, electronic media, McLuhan wrote, could be dangerous and destructive in the hands of large organizations and corporations. In the 1970s, environmental organizations were small, but the present-day landscape of environmentalism is populated by the types of colossal corporate players McLuhan warned us about.

In 1951 McLuhan published The Mechanical Bride, his first major, perhaps boldest attempt to push back against those mid-twentieth-century corporations determined to manipulate and exploit the collective public mind. The work is composed of a series of reproduced ads paired with sardonic commentary from McLuhan. Each coupling focuses on how ad men were using radio, television, movies, and print to manipulate the viewer, creating an unbalanced mental state that constantly craved consumption and entertainment for relief. For example, McLuhan reproduces a magazine ad for nylons and undergarments, which features a half-dressed, perfectly proportioned illustration of a smiling young woman. On its face, the ad poses a seemingly benign question of “What to wear?” But, as McLuhan points out, in altering the anatomy of the illustrated woman (think Photoshop before computers) the ad is a dictate, a mental manipulation in the form of a question that, bitingly, McLuhan rephrase as, “Can the female body keep pace with the demands of the textile industry?”

The way to escape the manipulation of advertising, McLuhan wrote, was to recognize its patterns and then, like the sailor who studies a deadly whirlpool in E. A. Poe’s story “A Descent Into The Maelstrom,” analyze its currents and ride them out, rather than struggling against them. In The Mechanical Bride McLuhan tried to beat the ad men at their own game, telling the reader that the work could be read in any non-sequential, halting, or jumping sequence that one chooses. Like the constant and disjointed flow of ads and commercial messages, McLuhan’s The Mechanical Bride is hyper-text in print, a daring and raucous departure from anything published in post-World War II America.

The way to escape the manipulation of advertising, McLuhan wrote, was to recognize its patterns and then, like the sailor who studies a deadly whirlpool in E. A. Poe’s story “A Descent Into The Maelstrom,” analyze its currents and ride them out, rather than struggling against them. In The Mechanical Bride McLuhan tried to beat the ad men at their own game, telling the reader that the work could be read in any non-sequential, halting, or jumping sequence that one chooses. Like the constant and disjointed flow of ads and commercial messages, McLuhan’s The Mechanical Bride is hyper-text in print, a daring and raucous departure from anything published in post-World War II America.

Unfortunately for McLuhan, and perhaps the rest of us, the book was too daring and raucous for the critics, with the initial run selling only a few hundred copies. Reviewing The Mechanical Bride in the New York Times, author David L. Cohn scorched McLuhan as someone who was “solemn as [a] Nazi propagandist(s)” in his railing against American culture as decadent and that McLuhan’s work lacked humor but not amusement. Ouch.

If McLuhan’s warnings about the tendencies of twentieth-century corporations to manipulate the public mind sound familiar, it is because most political or environmental organizations presently use some variation of the same tactic to raise money. It often goes something like this: “Warning! The sky is falling/being pulled down/burning because of (insert threat)! To stop/fix/reverse this, give us money, and make it quick!” The rhetoric is not designed primarily to inform the viewer about the issue but to create a state of emotional distress, one that can only be alleviated, the message makes clear, by funding the messenger. These tactics are shamelessly promiscuous, with no loyalty to any cause or ideology.

The rhetoric is not designed primarily to inform the viewer about the issue but to create a state of emotional distress, one that can only be alleviated, the message makes clear, by funding the messenger.

This brings us to many of the voices in the twenty-first century preaching a near-constant flow of dire news about the environment. They are, to put it bluntly, often shrill in their tone, alarmist in their predictions, and worst of all, publicly divisive in their effect.

Consider, for example, the state of the American West. Throughout the region, there is presently a serious and ongoing drought. By definition dramatic changes in how much rain does or does not fall in a region is climate change, and whether or not this drought is a permanent feature of a warming planet remains to be seen. But the shortage of water in the west is being driven by a deluge of corporate greed and short-sighted governmental policies, both of which are in dire need of redress and reform. And while hyperbolic statements from certain members of the United States Congress that “the world will end in twelve years if we don’t address climate change” certainly grab headlines, effectively “mind bombing” the viewer, they do nothing to build the cooperative networks of people and organizations needed to solve complex social and environmental issues such as water usages in regions that tend, on the whole, to be dry.

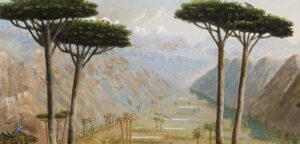

Looking deeper into The Mechanical Bride, McLuhan cautioned us against not only the tactics of media and advertising but also their long-term effects. Specifically, McLuhan was very concerned about how the advertising industry was remaking our entire folklore: that is, the stories that we tell ourselves about ourselves to understand who we are and what we doing here. Thanks to nearly seventy years of a non-stop ad industry, what was once a land-connected, outdoor-oriented American culture has been reshaped and replaced by a riled-up, reactionary, stay-indoors consumer culture. And ironically as the media-driven environmental rhetoric has gone up, the number of us who actually go outside and connect with the land, even if only for a walk in a park, has gone down.

Why is this?

One explanation might be the impact of certain mediums on how we think and feel. McLuhan theorized that when it came to electronic media, the platform has as much, if not more, effect on us than the content. Summing up this insight in his famous quip, “The medium is the message,” McLuhan was a canary in our social-economic coal mine, rightly predicting two important trends: One, that electronic mediums like televisions (and today computers and so-called smart devices) were so seductive that we would spend ever-increasing amounts of time staring at them; Two, that this would radically transform our behavior and the spaces that we live in. To test these theories, we need only look at the architectural transformation of the living room in the standard American home. What was once a space configured to turn people toward each other for connection and conversation has been transformed into a space where all occupants face a wall specifically designed to hold an ever-larger electronic platform, the flatscreen television. Mesmerized by flickering images of things that are not really there, we increasingly forgo those basic activities that make us human, such as movement and conversation, all for the sake of staring at a screen mounted on the wall or held in our hands. This dehumanization of our very human need for interaction is not just reshaping the spaces we live in, but it is also, as the sociologist Sherry Turkle put it, leaving us feeling alone even while we are together.

Mesmerized by flickering images of things that are not really there, we increasingly forgo those basic activities that make us human . . . .

Another likely explanation for our growing aversion to the outside is the law of unintended communication consequences. As the American writer Susan Sontag pointed out in her work, “Regarding the Pain of Others,” we must be very careful about using images and words that create dire and horrific pictures in the mind’s eye. Not only because such mental pictures stir emotions but because it is very difficult to predict which emotions are stirred. Thus, there is emerging and convincing evidence that environmental organizations that self-servingly replay video clips of a genuinely distressed Greta Thunburg decrying the loss of “my dreams and my childhood” are scaring the daylights out of the next generation, causing young people to shelter in place and just stay indoors. As McLuhan predicted, the use of media has worked many of us over completely, leaving us terrified of the environment and, increasingly, the future. In a study conducted by researchers at the University of Bath, 10,000 young people, ages sixteen to twenty-five years old living in ten countries (including the US, Britain, and India) were surveyed concerning their thoughts and feelings about the climate and our collective future. Seventy-five percent of the youth surveyed believed that “future is frightening”; and an unsettling fifty-six percent believe that “the future is doomed.” This is not good.

But let’s assume, for a moment, that doomsayers are right, and despite having weathered a few Ice Ages and a handful of mass extinctions, things are so perilous for planet Earth that we are all in unprecedented dire straights: “Mind bombing” the people, as Bob Hunter and Greenpeace did in the 1970s will not solve the problem. We are hardwired to kill or run away from those things that threaten us, the “fight or flight” response, and we tend not to care for or spend time in places that are frightening — this includes the outside.

But let’s assume, for a moment, that doomsayers are right, and despite having weathered a few Ice Ages and a handful of mass extinctions, things are so perilous for planet Earth that we are all in unprecedented dire straights: “Mind bombing” the people, as Bob Hunter and Greenpeace did in the 1970s will not solve the problem. We are hardwired to kill or run away from those things that threaten us, the “fight or flight” response, and we tend not to care for or spend time in places that are frightening — this includes the outside.

So what is to be done?

First, to borrow a line from a poster in 1939 pre-war Britain, we should “keep calm” in our communications about the environment, even in the face of real and pressing problems. Histrionics can motivate people to act in the short term, but they prove to be a liability over the long haul. We did not get into any of our current environmental problems overnight, and solving them will take time, cooperation, and resolution. Populations have limited amounts of emotional energy and a tendency to go tone-deaf and disengage if you scream too loudly and for too long into their collective ears.

Second, to break the stranglehold that media has on all of us, spend more time communicating with each other, about anything, without the use of electronic mediums: Write notes, cards, and letters. Stop and talk, or pop in for a visit, and when you do, linger awhile. In 1964 McLuhan published Understanding Media in which he pointed out that when we rely on technologies to do for us what we once did ourselves, such as communicate and connect, our capacity to do these things goes numb and atrophies. And the data is stacking up, wide and deep, that the more we rely on electronic mediums to communicate, the less connected we feel. Likewise, the more we rely on the internet to tell us the “right answer” to our problems, be they environmental problems or any other, the less capable we are of figuring things out for ourselves.

Third, develop (or increase) a deep love for being outside and the elemental connections that come with it. We are hardwired to feel better outside, a process called biophilia, and we can improve our mental and physical well-being by just spending time standing under a tree.

Finally, lead by example and encourage the next generation to join you out of doors. Take your children for a walk in the wood or by the water, or spend regular time with them in the garden. Reconnecting with the land does not, blessedly, require screens, video or mass-produced ads; we need only, as McLuhan said, “to turn off as many buttons as we can,” and together, just go outside.