Blueberries

Dr. Anthony Esolen

I’m getting to be an old man, and I regret many things I’ve done or left undone. But I will never regret one hour of picking blueberries in the woods.

My father first taught me to pick them. It was for pleasure, not need. But it was for need when he first learned it. He and his nine brothers and sisters used to troop several miles to a mountain place called Whisky Springs, where they spent many a warm day picking berries. They brought with them some pepperoni and bread, and a jug for the water they’d get cold from the spring. They filled their gallon pails and lugged them back to town, mostly to sell for twenty-five cents a quart. That was the early 1940s, and the family needed the money. It explained too why he always insisted on picking them clean, with as little dust and twigs and green berries as possible, and then he’d leave for last some bush where the berries were big and plump, to top off the pitcher and make it look really fine.

When I got big enough to wander the woods alone, I found my own favorite spot, a place where the retreating glaciers had heaped up big rocks in a jumble, with soil too thin for tall grasses and any trees besides the scrappy white birch, but the blueberries liked it very well indeed. But when I went with my father, we drove up to the top of the Archbald Mountain — it was always “the,” never without the article, as if it were a familiar thing, like “the” river that ran through our town, or “the” coal-mine strippings, or “the” field of red ash that was part of the leavings of the mine operation. We’d be alone at the top of the mountain, a bald old knob of a hill where the Army had set some sort of signal station, I suppose for monitoring invading missiles from Russia, which never came. We brought our collie along, too, to ward off the copperhead snakes, because a dog tramping through the bushes makes the snakes slink away.

When I got big enough to wander the woods alone, I found my own favorite spot, a place where the retreating glaciers had heaped up big rocks in a jumble, with soil too thin for tall grasses and any trees besides the scrappy white birch, but the blueberries liked it very well indeed. But when I went with my father, we drove up to the top of the Archbald Mountain — it was always “the,” never without the article, as if it were a familiar thing, like “the” river that ran through our town, or “the” coal-mine strippings, or “the” field of red ash that was part of the leavings of the mine operation. We’d be alone at the top of the mountain, a bald old knob of a hill where the Army had set some sort of signal station, I suppose for monitoring invading missiles from Russia, which never came. We brought our collie along, too, to ward off the copperhead snakes, because a dog tramping through the bushes makes the snakes slink away.

We wouldn’t talk. That was just as well. I was a quiet boy anyhow, and I felt closer to my father without the words. Sometimes I thought I’d strayed far off and I’d call for him, and he’d call back, and tell me to come on over his way because he’d found a bush whose berries were as big as marbles. “I’ve got one here like that too,” I might say, and that would be that, and we’d go on doing what we’d started, until our pitchers were full or brimming over.

We wouldn’t talk. That was just as well. I was a quiet boy anyhow, and I felt closer to my father without the words.

He died young, my father did, but I think of him always when I go to pick blueberries — or raspberries, blackberries, cranberries, lingonberries, gooseberries, cherries, wild strawberries, and saskatoons, those delicious pomes that only Canadians seem to know about, and fewer and fewer Canadians at that. When I pick the saskatoons, I sling through my belt a milk-jug with the top cut off, so I can have both hands free, just as my father taught me on the rare occasions when we went to a lakeside to pick the “high-bush” berries, whose bushes can grow twelve or fifteen feet tall. You do grab a branch by one hand, pull it down toward you, and pick with the other. It’s also how I pick cherries, after climbing up a tree or planting a ladder at its side. And then too I think of him, and of my Uncle John, who would drive a hundred miles from New Jersey back to his old homestead in our county, just to go pick the blueberries he loved, as he did when he was a boy.

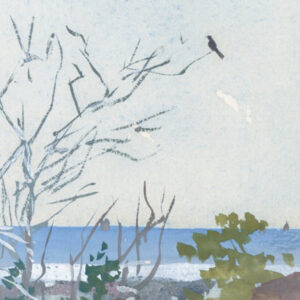

We live on an island in Nova Scotia in the summer, really the hinterlands, whose claim to fame is the old fishing village of Arichat, mentioned by Kipling in his novel Captains Courageous, which he wrote during the short time when he and his family lived in New England, and he got to know about the fishing schooners sailing in and out of Salem and Gloucester.  I’m aware that God’s bounty is rich on the Isle Madame, and that I don’t know the half of it, and that I take advantage of much less than half.

I’m aware that God’s bounty is rich on the Isle Madame, and that I don’t know the half of it, and that I take advantage of much less than half.

I know that there are spruce grouse everywhere, surely the dumbest bird God ever made, but good eating, I’ve been told. You’d have to set off a nuclear charge to get a spruce grouse to start from a branch fifteen feet up a tree. Their strategy, such as it is, is to stay absolutely still, and to pretend that they are invisible. You can spend ten minutes pitching rocks at one of them, as I once did, and still he won’t move. Had I a small rifle — bang! A nice Sunday dinner. We also have mackerel that wash in and out of a sort of funnel under a bridge near our house, and when that happens, you can catch a hundred of them in an hour, easily. And the tasty and unmistakable chanterelle mushrooms pop up in the shade under fir and spruce and hemlock trees, where the needles gather. And apples — tens of thousands of wild apple trees, with small but intensely apple-tasting fruit, right there for the taking. I’ve discovered, too, that bilberries grow up here and there on open hillsides exposed to the cold winds off the Atlantic, and the only reason I discovered it is that my dog started to eat them off a bush before I could stop him. “If they’re good for the dog,” I said to myself, “whatever they are, they’re good for me too,” and they were.

And apples — tens of thousands of wild apple trees, with small but intensely apple-tasting fruit, right there for the taking.

So I have picked all kinds of things there, and always been alone when I did it, because the people on the island have gotten out of the habit, and the youngsters have better things to do, such as spend hours on their computers, gaping at such soul-enlightening things as the latest video from a pop star who does not write her own songs and can only sing if singing is groaning, as if in labor pains or a kind of body-soul constipation. And when I come home, the berries we don’t save for pies and cakes go toward making jam — my wife and my daughter have it down to a regular science, and since the fruit is practically limitless, they can afford to use one part fruit to one part sugar, and that makes for jam such as nobody we know has ever tasted, intensely flavorful, since the fruit is wild and therefore richer in flesh than the blander and more watery commercial stuff, and since there’s more of it in a spoonful, along with the edible seeds we never strain out. We usually return to the States with two hundred to two hundred and fifty jars, some for our own use, some for gifts to other people.

“What’s it worth?” you may ask. That’s like asking what a kiss is worth, or what peace is worth. I might call it blue manna, what I gather. What do we live for? Surely heaven smiles upon this holiday kind of labor, the sweat that is close to the dew on the leaves. My father was a devout man, and I trust he has been taken to that place where nothing good on earth is ever lost, and there are no copperheads, for the venomous snakes are all in that other place where all the talk is of ambition, of profit and loss, of work that wears the soul away, of stunned deafness and no silence, of noise and no song, and of apples that turn to ash between the teeth.

Now, where did I put that jug?